Expressiveness Sound Design

One of my favourite topics is about one of the most helpful tools involved in music sound synthesis: Envelopes.

Years ago, I was searching online for essential tips on sound design and ended up in an interview with someone who worked in the industry. While I don’t remember who it was or what he was talking about, the one thing that struck me was how he explained that the most exciting part of his design was related to envelopes. In other words, he said that what made some sound designs “next level” was how they were used.

Every sound around us has envelopes, even constant background sounds such as a the low hum of a fridge.

In sound design, an envelope is a reactive control mechanism that shapes how a parameter, such as amplitude, pitch, or filter frequency, evolves in response to a gate (a signal that remains active as long as a note is held) or a trigger (a short, one-time event). Envelopes modify a sound’s dynamics, giving it motion and expression.

When you trigger a note on your keyboard or punch in some notes for your melodies or percussion, you’re using an envelope to shape the personality of a sound. If the envelope modulates the amplitude (e.g., volume, gain), it defines how it starts and ends over time.

There are two main types of envelopes:

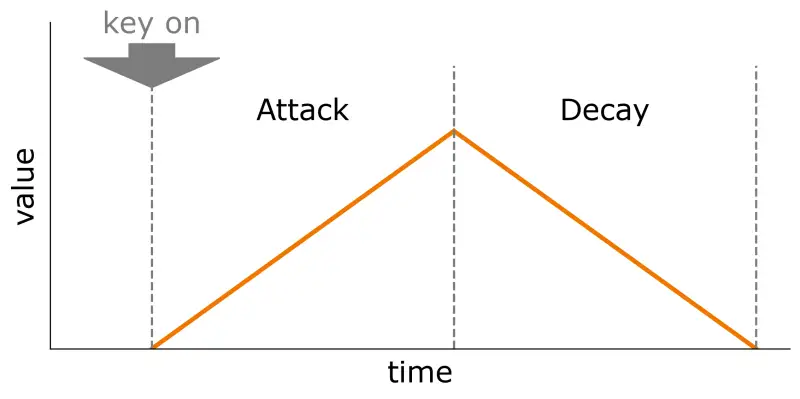

AD Envelope (Attack-Decay):

AD Envelope (Attack-Decay):

This more straightforward envelope consists of just two stages:

- Attack: The time it takes for the sound to rise from silence to its peak level after being triggered.

- Decay: The time it takes for the sound to fade from the peak level to silence after the attack phase is completed.

It is commonly used for short, percussive sounds or when simplicity is needed, as the sound always returns to zero regardless of how long the gate is held.

Since you don’t need to hold a key down for the envelope to work, a simple tap will do, and this is why we often use this one for percussion.

Rampage (Befaco)

This module is similar to another module named Maths. It is a double AD module, meaning that one trigger can trigger two envelopes at once or be used as a multi-stage envelope (see below) where the end of the first envelope triggers a second one. It can also trigger one another into a feedback loop, a technique named Krell patching.

This highly versatile module also has speed adjustment for envelope movement, from slow to fast, once again valuable for creating textures and movement.

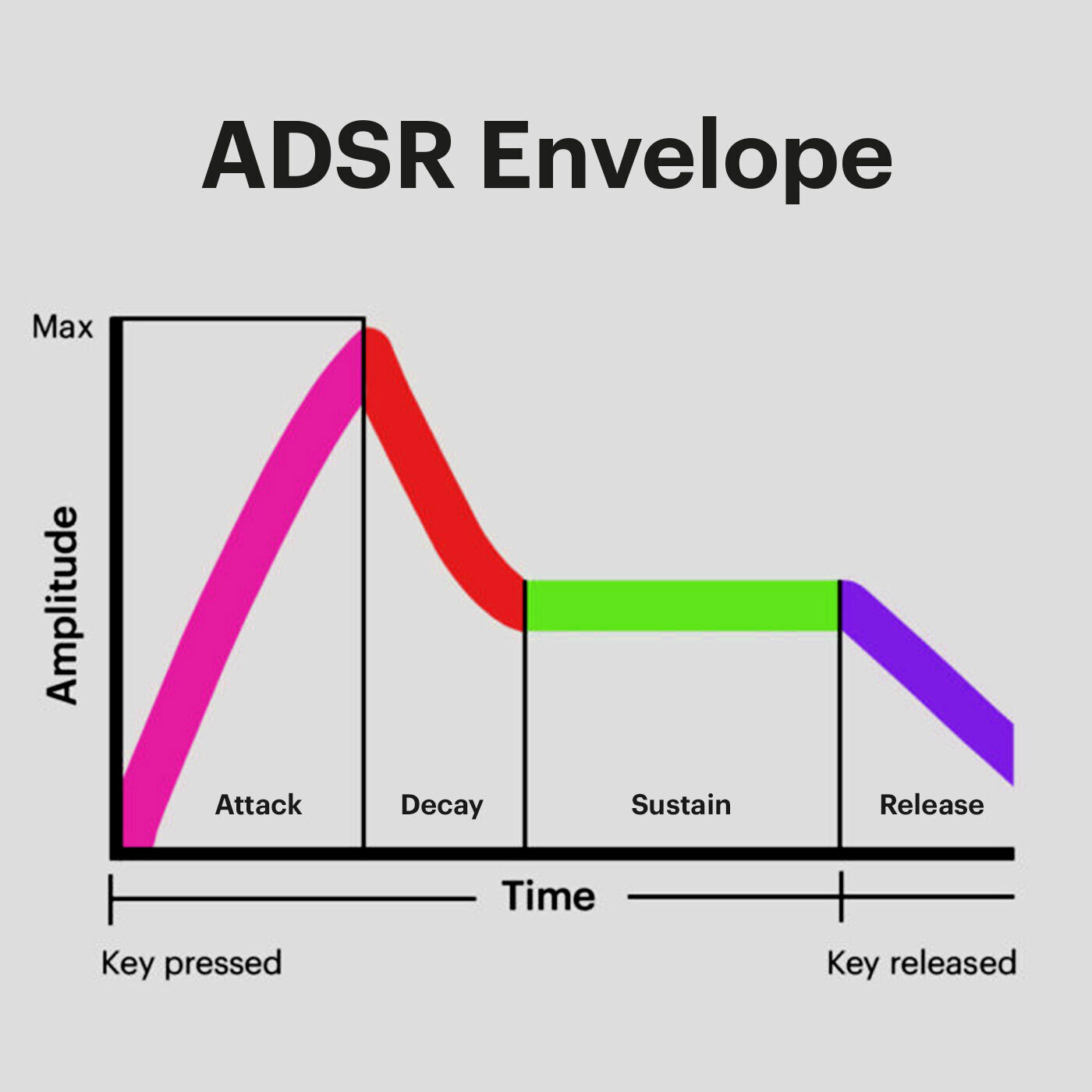

ADSR Envelope (Attack-Decay-Sustain-Release):

A more versatile and detailed envelope with four stages, often seen in synths. This one requires a gate to operate because it’s following the time of the gate itself. If the envelope’s settings are shorter than the gate, it will shift to the release stage.

- Attack: Time to rise from silence to the peak level when the gate is activated.

- Decay: Time to fall from the peak level to the sustain level.

- Sustain: A constant level is maintained as long as the gate is active (note is held).

- Release: Time to fade from the sustain level back to silence after the gate is deactivated (note is released).

This type is ideal for shaping sustained or evolving sounds like pads or leads, allowing for more dynamic control. It can also be used with percussion but must be longer than shorter sounds. Cymbals and gongs are good examples.

Ableton’s Envelope MIDI is a simple modulator you can map to anything in your project. It also has different parameter adjustments for tweaking it in detail.

Envelope Reactivity:

- When a gate signal is applied, the envelope begins shaping the sound according to its defined stages (AD or ADSR) and reacts dynamically depending on how long the gate remains active.

- The envelope completes its cycle regardless of the input length for a trigger signal, making it suitable for one-shot sounds like drum hits or effects.

Envelopes are fundamental tools in sound design because of their reactivity. They enable precise control over the evolution of a sound’s character over time.

A function and an envelope share similarities in that both are time-based modulators, but they differ in flexibility and application:

Envelopes:

- Typically, predefined stages (e.g., ADSR or AD) control how a parameter evolves in response to a gate or trigger.

- Envelopes are tied to musical events like note on/off signals and are specifically designed to shape sound characteristics (amplitude, filter cutoff, pitch, etc.).

- They repeat their behaviour consistently when triggered.

Functions:

- Functions are more generalized and programmable time-based modulators that perform various tasks beyond standard envelopes.

- A function can trigger a single event (like an envelope) and include custom curves, loops, or conditional behaviours (e.g., cycling, repeating with variations, or modulating multiple parameters).

- Unlike envelopes, functions may not rely on a gate or trigger. They can operate freely, following internal timing or external synchronization.

In essence, envelopes are a subset of functions purpose-built to shape sound, while functions are more flexible and allow broader modulation possibilities.

What Is a Multi-Stage Envelope (Chained Envelopes)?

A multi-stage envelope extends the traditional envelope concept by adding additional stages, creating a more complex and customizable modulation shape. It consists of multiple chained segments with their curve, duration, and target values, allowing for intricate and evolving modulations beyond the simple ADSR model.

One thing I like in the modular world is having multiple envelope modules with an EOC (end-of-cycle), where when one ends, you can have another one starting. If you have 3-4 envelopes, they can all have different settings, and the modulation will end up being like a function because it is more programming than static and repetitive.

The best application for this is for complex fluctuating modulations. Background design, textures and drones are good examples here.

Key Features of Multi-Stage Envelopes:

Customizable Stages:

-

- Each stage can have different time lengths, target values, and shapes (e.g., linear, exponential, logarithmic, or even user-drawn curves).

Chained Behavior:

-

- The envelope moves through each stage sequentially, often in response to a single trigger or gate. It can also loop specific stages or groups of stages.

Looping and Re-triggering:

-

- Certain stages or sections of the envelope can loop, creating cyclic behaviours (e.g., for LFO-like modulation or rhythmic effects).

- Some multi-stage envelopes allow conditional behaviours, such as advancing to the next stage only when a specific condition is met.

Applications:

-

- Multi-stage envelopes are perfect for creating evolving textures, rhythmic patterns, or modulating parameters over extended periods.

- They are often used in modular synthesis and sound design software like VCV Rack, where granular control over modulation is needed.

Practical Example of a Multi-Stage Envelope:

Imagine a multi-stage envelope used to control filter cutoff for a pad:

- Stage 1 (Attack): The cutoff rises slowly from low to high.

- Stage 2 (Decay): The cutoff drops slightly to add subtle warmth.

- Stage 3 (Sustain 1): The cutoff holds steady.

- Stage 4 (Rise): The cutoff climbs again for a sweeping effect.

- Stage 5 (Release): The cutoff fades out smoothly.

This setup can loop stages 2 through 4, creating a hypnotic movement in the filter.

Followers as Mimic Envelopes

An envelope follower is a tool that extracts the amplitude shape (or envelope) of an incoming audio signal and converts it into a control signal. This control signal modulates various parameters in a synthesizer, effect, or other audio processor. While it shares similarities with traditional envelopes, it differs in how it derives its modulation shape.

Similarities Between an Envelope and an Envelope Follower:

Shape Control:

- Both create a time-based modulation shape that can control parameters such as amplitude, filter cutoff, or pitch.

- In both cases, the “envelope” defines how a parameter evolves.

- In many cases, envelope followers have rise-and-fall controls that are used to smooth out the shape of the read signal.

Dynamic Modulation:

- Both can introduce expressiveness and movement to a sound by dynamically modulating parameters.

How an Envelope Follower Works:

This is a modulating tool you put at one point of your chain, and it will read the incoming signal. The signal read is then translated into a modulation. It usually comes with a Gain knob so you can control how much movement you want it to read.

Input:

- The envelope follower analyzes an incoming audio signal and measures its amplitude (volume) over time.

Output:

- It generates a control signal (CV or MIDI automation) corresponding to the input signal’s amplitude.

- For example, a loud signal produces a high output value, while a soft signal produces a low output value.

Filtering:

- To avoid overly rapid or jagged modulation, many envelope followers include smoothing or attack/release (rise/fall) controls.

Ableton 12.1’s new Envelope Follower has a Sidechain signal, allowing you to intercept the signal from another channel and mix it with the incoming signal, creating a more complex movement that refers to 2 independent sources.

Using an Envelope Follower to Modulate Another Sound:

Extracting Modulation:

-

- The envelope follower “follows” the dynamics of one sound (e.g., a drum loop, vocal, or bassline) and creates a modulation signal that mirrors its amplitude shape.

Applying Modulation:

- This modulation signal can be applied to another sound’s parameters, such as:

- Filter cutoff: Make the filter of a pad “pulse” with the rhythm of a drum beat.

- Amplitude: Shape the volume of one sound (e.g., a synth) based on the dynamics of another.

- Pitch: Add a wobbling or dynamic pitch effect driven by the input signal.

Practical Example:

- Imagine a drum loop being fed into an envelope follower.

- The envelope follower generates a modulation signal based on the drum’s transients (e.g., the kick and snare peaks).

- This signal controls the filter cutoff of a synth pad, creating a rhythmic filtering effect synchronized with the drum loop’s dynamics.

Creative Uses of an Envelope Follower:

Sidechain-Like Effects:

- Use an envelope follower on a kick drum to duck the volume of another sound, similar to traditional sidechain compression.

Rhythmic Modulation:

- Apply the rhythmic envelope of a percussive sound to non-percussive elements, such as reverb or delay levels.

Dynamic Layering:

- Use an envelope follower to match the dynamics of a secondary layer (e.g., adding texture to a lead by dynamically modulating it with a vocal track).

Cross-Synthesis:

- Combine the dynamics of one sound with the tonal qualities of another, creating hybrid and expressive textures.

An envelope follower is similar to a traditional envelope in providing dynamic, time-based modulation. However, while conventional envelopes are pre-programmed shapes triggered by a gate or trigger, envelope followers derive their shape directly from an audio signal. This makes them a powerful tool for dynamic, real-time modulation, enabling producers to “borrow” the amplitude shape of one sound and creatively apply it to another.

How I use Envelopes and these movements in electronic music

There are multiple insights I discovered while studying sounds, and one of them is how the sound fluctuates and modulates based on an envelope more than LFOs. For instance, deeper kicks often use envelope-based pitch shifting for multiple purposes.

- A fast pitch shifting up can make a kick’s transient snappier.

- A medium shifting down will create a downward pull, with a feeling the kick is dropping low towards your hips.

Both are common and have the advantage of bringing life, therefore making them more engaging. If the envelope constantly changes, it will feel more acoustic sounding. Considering that one envelope shapes the kick’s amplitude and another one, the pitch, reminded me of what the interviewed sound designer mentioned. I realized that when I use a sound, I always try to have 2 to 4 envelopes and an envelope follower. It became a “by default” macro for my channels.

The advantage of having multiple envelopes is you have them have 3 ariations: slow/fast/medium attack and slow/fast/medium release.

That realization was a 180-degree shift compared to my old approach, where I’d use multiple LFOs per channel/sound. Something about LFOs made the sounds feel more mechanical, while envelopes made the sounds more organic/human. It was also a way of ensuring that one sound would shape the characteristics of the sound of another channel. It made me stop using side-chaining compression and instead would use amplitude side-chaining. But that’s just one example because the applications are pretty vast.

Ideas to explore:

- An envelope is used to open up an LFO’s amplitude. If an LFO modulation is constant, it will give more of a mechanical result. Still, if the envelope opens the amplitude, there will be this little temporary movement (think of bird singing). An envelope for exciting evolution can also alter the speed of the LFO.

- Opening the wet-dry of an effect such as a reverb.

- Envelopes are used to modulate the panning of a sound to make room for another. This is an excellent alternative to predictable aut0-panning and can also avoid phasing issues in some cases.

- Using the envelope, a sound but inducing a delay can create a cleaner call and answer for your arrangements.

- Create a MIDI channel without an instrument, but instead, add a few envelopes. The envelopes will follow your notes whenever you press keys on your keyboard, and you can then assign the envelopes to a few parameters across your project.

For mixing, envelopes have helped add cleanliness and clarity to songs. Side-chain compression became obsolete more than ever for me as compression alters the envelope more than an envelope will. Compression also alters the density of a sound, which is not always necessary.

You can also create a macro that captures the movement of a sound within a frequency range (e.g., everything over 4kHz, where transients are). Transient shapes can be used to make the texture for another sound.

The exploration is vast here, and I’d love to read your application.