Artistic Integrity and Music Theory

Last week, in one of our online coaching sessions, we discussed the importance of music theory. In describing my own opinions on the importance of music theory, I’d like to outline different stages of music discovery I’ve gone through during my life. In this post, I will also elaborate on some of my reflections on the current state of music itself.

It’s hard to pinpoint the first time I heard electronic music, but it was probably in the ’70s, and obviously, I fell in love with it. There was a whole science fiction trend at the time, and anything related to sci-fi was characterized by electronic music in the score. During that time, in a sea of pop and rock, electronic music was the oddball, not sounding like anything else. It had its own rules, and while some people were making electronic covers of known songs (which I’ve always hated deeply), I had an appetite for original music.

In the early ’80s, I was really into break-dancing and early electronic hip-hop or electro, which was all the rage. The use of 808s was common, and for me it was also instant love. What I discovered later on was the strong bond between early hip-hop and jazz. Recently, I watched a Blue Note documentary which retraces the roots of hip-hop and jazz, which was very refreshing.

What’s inspiring in this documentary is how this label, in its beginning, was trying to really give artists a chance to share a very personal take on music, and they didn’t follow trends or worry about sales. What was shocking about the film was that, for most part, the artists and label owners talk about what they do largely coming from the same perspectives as electronic musicians do about their own craft.

This type of vision has always resonated with me; what makes an artist wholesome is striving to be personal before anything else. If that’s obvious to you too, I’m sure you also know it’s not the case for many others who might be reading this post. This is why I became close friends with Bryan, who I make jazz with. He’s been playing sax for more than 45 years in all kind of contexts. When it comes to learning music, knowing chord progression rules and things like the circle of fifths, he’s probably the best person to talk with.

We had a talk about those so-called “rules” once. His point of view was very clear: knowing fewer rules might actually keep you more open to making things that are ground-breaking rather than thinking that certain things shouldn’t be done. I can related to this, because when I hear about “engineering rules”, I often feel like I’m preventing myself from doing certain things by adhering to them. Bryan is not interested in guiding me with respect to melodies. “Ya gotta break patterns, man!”, he’ll say, sometimes talking about how it works in free jazz.

“Music rules got blown out of proportion in the ’80s when musicians understood they could make a lot of money if they knew the tricks. Then everyone were more interested in repeating known recipes than making something personal,” he says. We have discussed how historically music elitists came up with serious rules to keep music-making limited to wealthy people who could afford music classes and thus it became less available to the poor. The dialog around music theory has traditionally been downwards, from the higher classes to the lower class—one way communication.

Jazz made music more open and accessible. The early beginnings of the rave days (circa 1987-1992) where music and the scene was really about inclusion and a big F-you to the music industry had a similar ethos. There was a lot of tension back then between electronic music and other genres. Electronic music was often misunderstood, mocked and put down, probably because it was the exact opposite in terms of values and ways of life.

From the early ’90s until around 2010, one of the most important values in most branches of electronic music was a sense of novelty. In my early rave days, we’d attend to be musically challenged. We wanted to hear music that we never heard before, and we even wanted to be disoriented. You’d have DJs dropping a huge mish-mash of different styles, and beat-matching was not as important as it seems to be now. It got more and more organized and popular DJs became the ones that were more structured, and eventually DJs started playing sets of one genre alone. One genre would emerge, stay for a while, and then become “bad” until another one usurped it as it faded into the past. This progression had many victims: Trance, Techno, House, Drum and Bass, etc. It was pretty different from today where there’s room for everything and artists are the ones to come and go instead of genres. Maybe they never really “go”, but the media focus often shifts to others in the same genre who are slightly “different”.

But let’s get back to music theory and academic chord progressions.

Often people make melodies based on some concept or rule they have in mind, or something they’ve heard before. One thing I hear a lot from people is that when they read about music theory and then try to apply it in their own work, they sound cheesy or too pop-y. So the question is, is there a way to know rules regarding melodies and still make something that sounds right?

That’s a bit of a hard one to answer.

It’s either you understand the tones and keys associated with a genre first and then try to reinterpret them in your own creative way, or you don’t. But to me, this raises some issues regarding artistic integrity—perhaps you want to work within a genre but still create a strong sense of originality. Is that possible?

Well, if you chose a genre that really speaks to you that you want to work in heavily, that’s a certain decision you make about who you are as an artist. But in my opinion, the quality of the vocabulary you can develop in electronic music comes—first and foremost—from understanding sound design.

That said, understanding music theory is a huge help in understanding how to strike a particular note. There are numerous tools out there to help you improve your tonal and theoretical knowledge. Here are a few:

- Instascale: Not familiar yet with this one, but I’ve heard good things.

- Scaler: For helping you understand chord progressions by proposing what could follow your melody, based on a genre.

- Melodyne: one of the most used plugins for pitch correction.

- Captain Plugins: The complete suite gives you access to tools that facilitate melody-making, pitch detection, bass-making and can make a huge difference in creating musical structure.

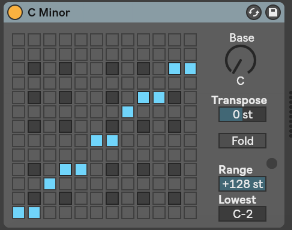

One thing I do a lot is work with my reference tracks using a pitch detection plugin (Mixed in Key, studio edition) and then will have that as a starting point. Then if you want to generate a different starting point, I’ll use Rozzer (Free Max patch) that generates a random pattern. That usually helps me find a motif for a song. Andrew here also has a few good suggestions:

I find that one thing that helps me a lot about making melodies is to work with what’s proposed instead of trying to control the output too much. If you start working with an expected melody in your head, you might spend hours trying to recreate it and it will end up sounding like crap. You sort of need to find the right melody for the right sound. That’s where it’s easy to go down the rabbit hole.

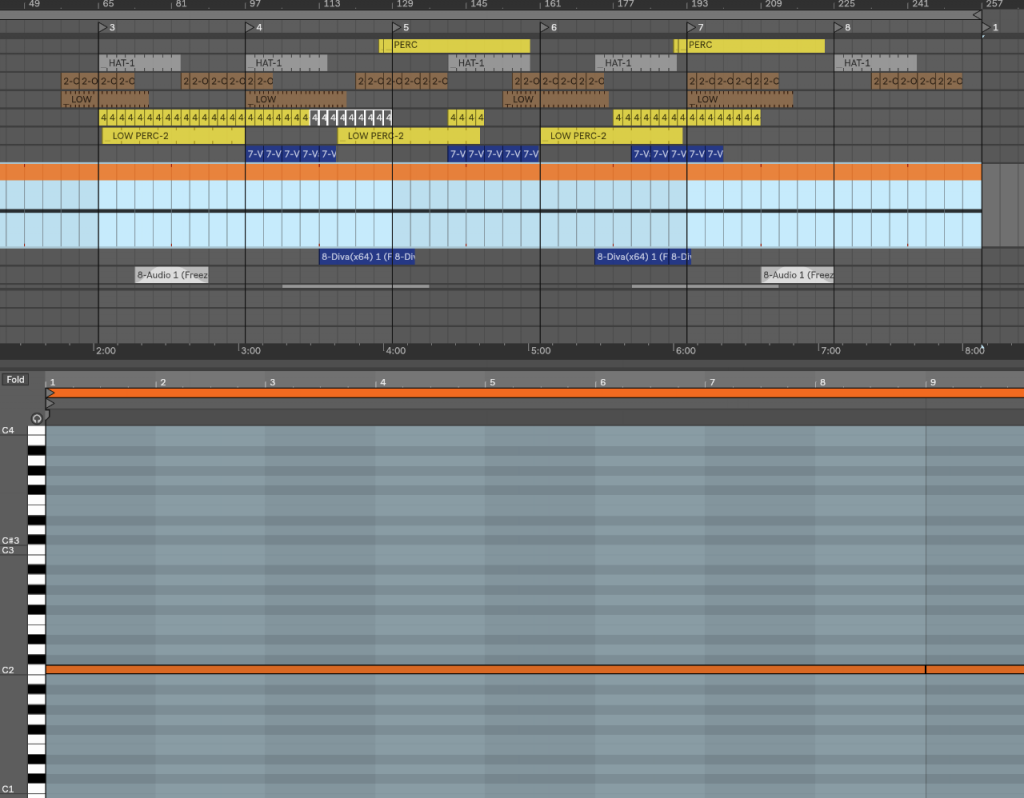

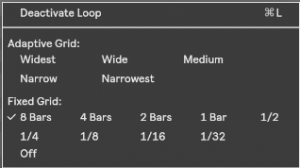

This is why if you work with what you have and try to get the most out of it, you might end up with something more original. I’ll record a lot of MIDI ideas and usually will go back to them and try a large series of presets until I find what feels like a perfect match, then tweak the sounds (this is where the sound design knowledge comes handy).

In this blog I frequently talk about remaining open-minded as much as possible and letting go of control. The notion of having control over what you do comes with practice. Same an understanding of musical theory. You need to make a lot of projects and a lot of songs to become more fluent and understanding in what you do. But to get there, first you need to really let go!