Electronic Music Is More Than Making Tracks

People have become increasingly interested in making electronic music in the last decade. I find it more exciting than people getting into DJing. It’s clear to me that one or the other is a hobby that everyone who enjoys electronic music should explore. As you explore the art of DJ, you learn how to dig, get familiar with the roots of artists you love, discover music you didn’t know you loved, and build some obsession over tracks. It’s a fun hobby that fuels the scene, supporting artists and labels and feeding more energy into what you believe in.

Making music is a pretty deep activity. I mean it. Some people get curious about making beats, and before they know it, they’re engaged in an inner journey where they rediscover parts of themselves and create sounds they never thought possible. Making music mirrors its creator’s psyche, reflecting subconscious emotions and triggering memories.

Photo by James Kovin on Unsplash

Maybe you’ll think I’m crazy, but most people who have been exploring the art for a while will confirm that it’s not so silly. This is why I get it when someone wants to make songs first, but I am also excited to tell the newcomer that there is more to explore than making tracks. What’s a bit tricky to explain is that to make tracks, you need to do multiple activities first. Making a song is like writing a story or a novel. You need to live some adventures first to share a story. Or perhaps you have a lot of imagination, but real stories always bring substance.

I like to see songs as stories from the studio. They are a collection of moments built into a more cohesive narrative. Sometimes, a few related stories can also be paired into a conversation.

Regarding categories of songs, in my case, I have two main buckets:

- Reference-inspired music: This refers to songs that are built with a precise purpose, such as making music for DJs, and is built to fit sets.

- Personal agenda: collecting moments and miniatures and finding sounds that I would love to put into a live performance where I record the outcome.

The issue I see for people who start making electronic music is that they focus on creating a song but lack the experience, tools, and general workflow to get things done. They will then compare themselves, and the gap between what they made and other people’s music will be significant. Many want to make a personal song combining the two categories I mentioned. This is even more difficult because the person will lack one of the primary essential music skills: vocabulary. That skill comes with playing, rehearsing and repeating the techniques.

I found many tutorials on making songs and known artists showing how they made music or how to make one from scratch, but this is a steep activity for a newcomer. We could relate to that kind of video, such as sharing how to build a house. It is helpful, but you’ll practice someone else’s way of working, and it won’t show all the learning they’ve been going through, which includes failing, dealing with various issues and how they resolved them. Electronic music is supposed to be a playground where you play with all those toys and software to see what comes out of it, and then, down the road, you record something you want to share.

To record something without exploration is the equivalent of sharing a made-up story that you haven’t lived: it lacks the essence. Memorable stories are partly inspired by personal experience.

Making sounds without a purpose might not be romantic or exciting, but it is an activity that develops deep listening. That skill is essential for understanding sound, reverse engineering what you imagine, and mixing. Sitting there and listening to sounds you make or have found is valuable.

Besides making music, sound activities that have to be added to your rotation of studio sessions should include:

- Listening to music.

- Listening to samples, videos, non-related sounds.

- Update plugins and gear.

- Learn a specific effect by testing all the knobs/options.

- Backup projects.

- Rename and organize past projects and ongoing ones.

- Use MIDI controllers paired with plugins and play with them.

- Design one sound at a time: ex. Bass hit or percussion.

- Turn loops into structures

- Create Mood boards and fill them with samples, designs, and sounds.

- Analyze Reference tracks and create templates for them.

- Modular patching.

- Create grooves alone

- Create Hooks alone

- Create beats alone

- Design an arpeggio.

- Try chord progressions.

- Deconstruct the song structure of a project of yours and see what are the different alternatives.

- Practice playing an instrument or a keyboard.

- etc.

I will share some activities and exercises I do daily that you can also do. These provide me with some ideas and remind me that electronic music is more than just making songs; it’s just spending time tweaking, listening, and adjusting.

Studio Activities to Try

Here are eight studio activities that mix challenge, logic, and analysis. Each is designed to be a focused exercise in sound exploration that lets you practice a new skill and gives you material to play with at the end. These exercises allow you to treat individual sound elements as mini-compositions (miniature) while keeping things structured enough to evolve into a conclusive five-minute segment.

Focus: Parameter Modulation Mapping

Challenge: Explore manual modulation with the 2-hands Technique

Activity: This requires a MIDI controller and mapping some parameters to a plugin instrument or effect. One of the most straightforward yet most potent explorations you can do is to map two knobs to 2 parameters. Then, using your hands, you’ll explore the different results when one hand does something while the other does something else. As a starter, if you need an idea, you’d control the frequency cutoff of a filter, and the other parameter would be the resonance.

What happens when you move slowly one parameter while the other squiggles quickly?

What does it sound like when the two move in opposite directions, quickly vs slowly?

You could ask yourself many questions, but being curious is the best guide.

Outcome: This transformative manipulation can drastically shape sound. You might want to add a limiter immediately to avoid hurting your ears. Recording the movement can test various sound sources through your effect. Resample everything.

Focus: Layered Texture Sculpting

Challenge: Create layers for a sound to make it more complex or richer.

Activity: You can layer textures to a simple-sounding sample using an envelope follower and a few filters. If the sound is mostly a mi-oriented synth, you can layer higher-pitched texture by putting a filter in highpass mode. Since many sounds have content in various areas of the frequency spectrum, you can explore parts of it with an EQ that isolates a section. You can also practice FM modulation to make the sound richer and then have fun with multi-band processing (eg. compression or saturation) to blend it.

Outcome: Practice adding layers to sounds, which gives you options when exploring new hooks. You can use previous experiments,, or if you build macros while exploring, you can create them on the fly.

Focus: Micro-Rhythm Manipulation

Challenge: Explore a sound when repitched, stretched or sequenced.

Activity: There’s this interesting fact that a sound in a library can have multiple lives, just like a cat. You can use the same sample multiple times, and to avoid repeating yourself, you’ll change it so it feels anew. Changing pitch is one way of exploring a sound’s potentially new outcome. Pitch it down for darker moods and high for exciting overtones. Explore the sound in a different scale, as a chord or reversed. Changing its length and sequencing can also turn it into an unpredictable turnout.

Outcome: After resampling the new ideas, you can save them as new hooks or post them on mood boards that need fresh air.

Focus: Algorithmic Sequencing Experiment (Or any sequencing that isn’t usual to you)

Challenge: Use an algorithmic sequencer or generative tool to create evolving note sequences or parameter changes.

Activity: You can record the MIDI output to new clips using a complex sequencer or MIDI clips with probabilities on some triggers. Recording multiple new clips allows you to save practical and fun sequences to reuse. In Ableton v12, you can make a drum kit and then shuffle the sounds with similar ones. Shuffling sequences and drum selections allow you to preview sounds with a specific sequence. Sometimes, we have a melody we love, but the sound doesn’t fit, and vice versa. Exploring one or the other lets you see a broad palette for a selection. Algorithmic sequencing is a powerful tool to spit out ideas from your habits since you’re not in control of the sequence.g

Outcome: If you save them, the result is in 3 spheres with new drum kits, midi clips, and audio clips.

Focus: Resampling and Transformation

Challenge: Reshape a sound entirely

Activity: Using the option to record modulation to clip in session view, add multiple effects of your choice on the channel of the sample and then record yourself moving parameters. Tieing your modulation recording to a loop-based time creates a lot of change to the initial sample. When we play with effects, we rarely automate multiple parameters at once, so this activity is about exploring exaggeration and going to places you might not explore. Once you have some action going, resample the entire playful session.

Outcome: Recording a long exploration as this will always offer alternatives to the original idea. Those recordings can be new hooks or extra material to support the initial sound.

Focus: One-Plugin Challenge

Challenge: Choose a single instrument plugin and use it exclusively to sculpt your sound for 5 minutes.

Activity: Similar to making a miniature, this activity is about taking enough time not to achieve anything other than using your curiosity and seeing what comes out of it. Very often, we are task-driven with something in mind, which narrows the outcome of what your tools can do. Set your root key to C to resample the exploration in those moments. Being in C will let you import the recording to a sampler for easy manipulation.

Outcome: Limiting your tools forces you to explore every nook and cranny of a plugin, and not having a goal keeps you open to finding sounds you aren’t usually going far.

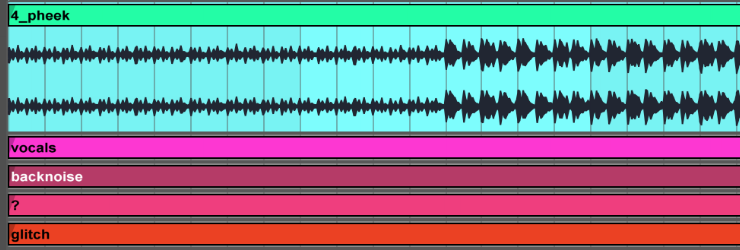

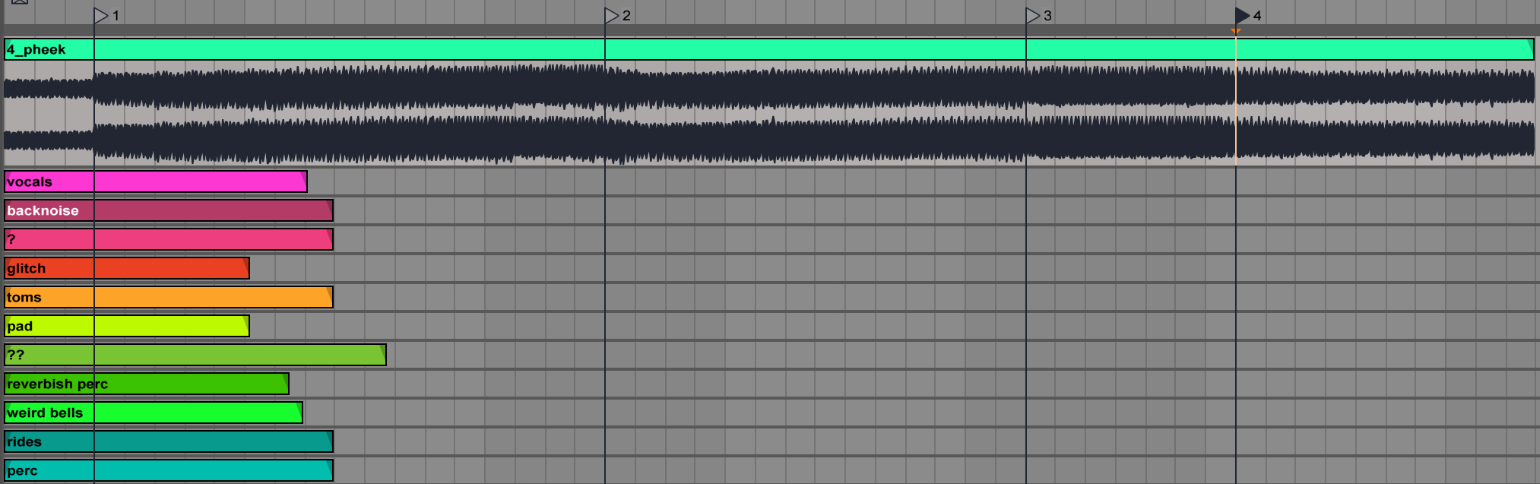

Focus: Dynamic Arrangement via Automation

Challenge: Turn a simple loop into multiple versions of itself using generative techniques.

Activity: Use the follow-action option in the session view to select multiple clips with a hook and create variations. The idea is to start with a simple loop, but the outcome will be different each time you play it. The record button allows you to save the order of the clips played, creating new hooks and unexpected arrangements.

Outcome: Either you resample the session or record the clip launching activity, but the outcome will provide a way of exploding the initial loop trap one can fall into. You can also revisit old projects and apply the same activity to recycle solid ideas in alternate versions of themselves.

Focus: Spatial Field Exploration

Challenge: Explore using space through panning, reverb and filters

Activity: Using a few samples from a new project or idea, spend time meticulously positioning them in space using panning. Quite often, that production phase is overlooked and left to be done at the end, either in the mixing phase or at some other point. Taking the time to explore what a sound can be like in the panning distribution can reveal potential flaws or strengths of a sound.

Outcome: The recorded performance might inspire spatial arrangements in larger tracks and help you consider sound positioning as a compositional element. Sometimes, moving around a sound will help make sense when paired with another. It’s a nice activity to listen to how sounds relate to each other, but from a spatial perspective. Also, exploring reverb use can give a new mood to the most straightforward sound.

Focus: Preset Owning

Challenge: Explore all the presets of your plugins and tweak them.

Activity: It is an enjoyable experience to go through all the presets of a plugin or synth and modify them to taste. You can, after that, either save them over the original preset or as a new one. Electronic musicians often disdain using presets, but you can see them as a starting point. You can also make them yours by changing them to your needs. Going through multiple presets helps you understand how a specific plugin works and how to configure it to achieve a particular result.

Alternative: My friend Jason likes to try to “break” plugins by pushing them to extreme settings to see what happens. By pushing them far, you can then roll back to less intense results.

Outcome: An expansion of your presets and a better understanding of your tools.

If you have suggestions, please share!