Upgrading Melodies with Articulation

In the diverse and ever-evolving world of electronic music, countless aspiring artists and producers are diving headfirst into the sea of music creation. With technology at their fingertips, creating music has never been more accessible. However, this ease of access can sometimes lead to a contentment with simplicity, especially for those who may not have a traditional background in music theory or composition. Yet, the realm of music, with its deep roots and intricate branches, offers a vast landscape of possibilities waiting to be explored.

It’s no wonder that trained musicians are often overlooking electronic music and will say it’s not “real music.”

I find that what makes an artist sound pro in their melodies compared to someone who start is often related to articulation, which we will cover in this post.

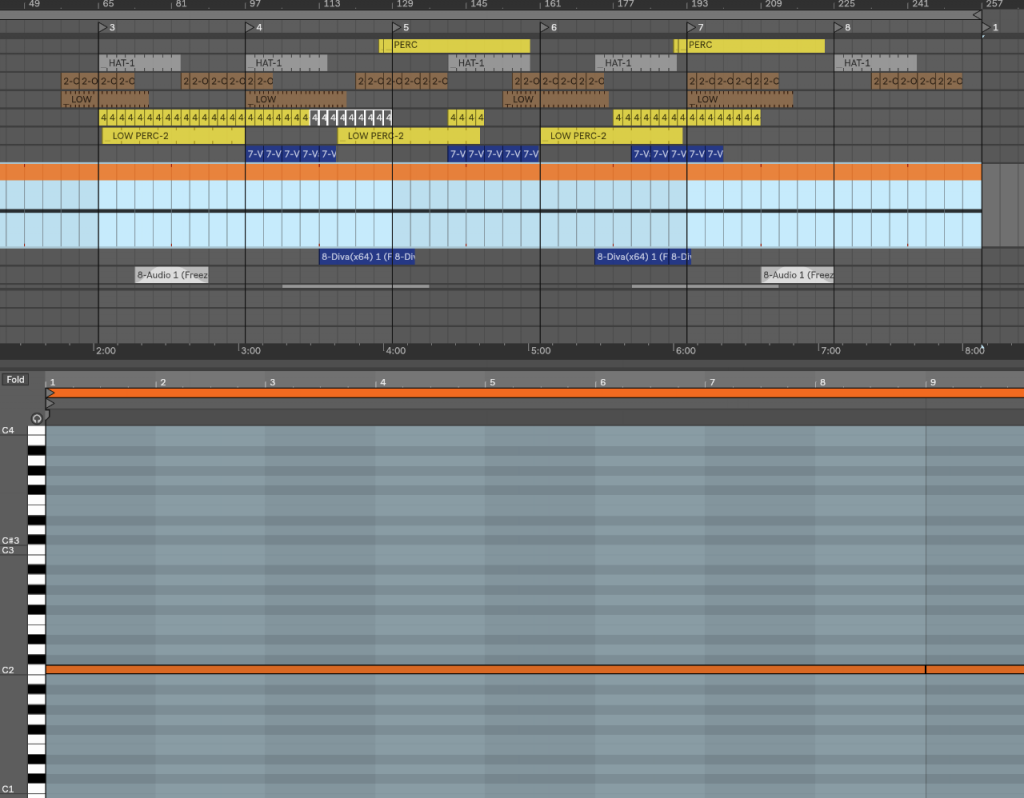

For many, the journey into music production begins with loops – those repeating sections of sound that form the backbone of many electronic tracks. Loops are the building blocks, the starting points from which entire tracks can emerge. But what happens when the novelty of looping fades, and the desire to craft something more complex and personal arises? This is where the concept of articulation comes into play, offering a gateway to elevate a simple loop into a rich tapestry of sound.

(Inside note: At the moment of writing this, Ableton just announced version 12 of Live. Some of the elements mentioned below will be covered in solid ways for that version but since I haven’t tested it yet, I can’t really expand on it yet.)

Articulation in Music to Elevate your ideas

Articulation in music refers to how notes are played or sung, influencing their transition, duration, and overall character. In electronic music, articulation can transform a basic loop into a nuanced and dynamic piece. If we were to compare two extremes, we could put on one side, loopy techno as not very articulate and on the other extreme, an experienced, jazz vocalist.

It is much more than just accent and velocity as many think. Those are just a fraction of what’s possible.

Let’s delve into the different types of articulation and how they can add depth and complexity to your music.

- Staccato: This indicates that notes are played sharply and detached from each other. Staccato notes are typically short, light, and separate.

- I find that in the low end range, kicks and bass notes have a much better clarity when short. You might not want short basses or kicks all the time, so you could alternate the gate length to have variation.

- Melodies that are staccato work well with arpeggios and bring a fast mood to a song, excitement and movement.

- In melodies, staccato also gives the impression of bringing a delicate touch.

- Legato: Opposite to staccato, legato articulation means that notes are played smoothly and connected, with no noticeable break in between. This often creates a flowing, lyrical quality in the music.

- Accent: An accent mark indicates that a note should be played with more emphasis or force compared to the surrounding notes. It stands out due to a stronger attack. We often use it in percussion as we mark where the groove has emphasis.

- Accents in a pattern accentuate the groove. If you are using some grooves, they also enhance accents at given points so consider that.

- It can also be described as adding an assertive tone to a note.

- Tenuto: This suggests that a note should be sustained for its full value, or slightly longer, often with a slight emphasis. It can add a sense of weight and importance to a note.

- When programming a pattern, I like to keep my high point velocity around 100 (of 127) which gives headroom for notes with emphasis.

- Marcato: This is a stronger form of an accent, where the note is played much louder and with a sharper attack. Marcato often creates a more pronounced and emphatic sound.

- That one would be at 127 in velocity.

- In music, there can be a part in marcato, meaning that a section is played with stronger impact.

- Fermata: This indicates that a note or a rest should be held longer than its usual duration. The exact length is typically left to the discretion of the performer or conductor.

- What makes a groove, an articulation are pauses. It’s good for dynamic range but just like when someone talks, pauses are crucial to understand the sense of a phrase.

- Portato: Also known as mezzo staccato, it’s a combination of legato and staccato. Notes are played somewhat detached, but not as sharply as staccato, and with a connection similar to legato.

- Glissando: This is when a performer glides from one note to another, playing all the intermediate pitches. This is common in string instruments and the voice.

- Often used for acid basslines.

- Slur: Notes are being played, blended all together. I think it’s similar to a legato but it’s of a way of creating “syllables” sound where they’re a bit mashed up.

- Trill: A rapid alternation between a note and the one above it, creating a fluttering sound.

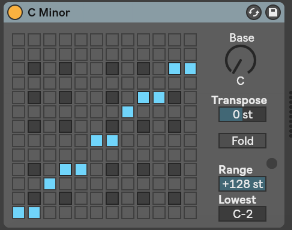

- I like to do this with a 2 notes arp.

Now, let’s explore how to apply these articulations in digital audio workstations like Ableton and modular environments like VCV Rack.

Examples

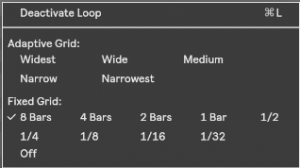

Staccato: In Ableton, you can achieve staccato by shortening the length of MIDI notes. You might also use a fast attack and release in an envelope on a synthesizer. There’s a MIDI tool named Note Length that can you can use to modify the duration. Any synths has an ADSR envelope and by playing with the decay/release, you can control the length, making any sound shorter, into staccato.

In VCV Rack, consider using a gate modifier or an envelope generator with a short decay to create sharp, short sounds.

When and why to use: Useful when you want to to introduce movement and a sense a density, in a rhythmical way. Short notes fill a space as well as leaving room for other elements. A good example would be tribal music.

Legato: For legato, ensure that MIDI notes overlap slightly in Ableton, and use a synth with a glide or portamento setting to smoothly transition between notes. When you use a midi clip, there’s an option for Legato that will stretch all notes to their longest option until it meets another note.

In VCV Rack, you can use a longer envelope decay and sustain, with a portamento module for smooth pitch transitions.

When and why to use: This can be good for thick melodies, pads, longer synth notes which create a nice background or the front part of a song.

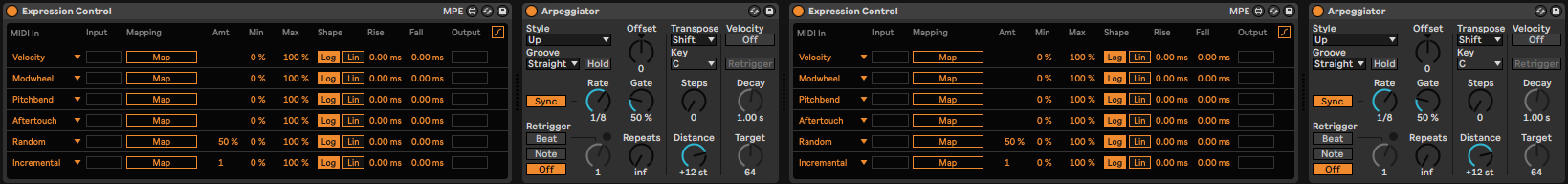

Accent: In Ableton, you can increase the velocity of specific MIDI notes to create accents. You might also automate volume or use a transient shaper plugin. In VCV Rack, use a velocity sequencer module to modulate the amplitude or filter cutoff for accented notes. I like to pictur

When and why to use: As said, it’s useful in a groove but it can also be a sporadic moment in a song as well to create a sense of dramatic impact with a feel of heavy impact.

Tenuto: Emulate tenuto in Ableton by extending the length of MIDI notes slightly and using a slight increase in velocity. In VCV Rack, a combination of longer gate times and subtle amplitude modulation can help achieve this sustained emphasis.

When and why to use: Little arps do well to bring secondary melodies, enhancing, supporting the main one or simply to add decoration.

Marcato: For marcato, increase the velocity significantly in Ableton, and consider using a sharper attack on your envelope. In VCV Rack, use a combination of high-velocity settings and an envelope generator with a quick attack and a moderate decay.

When and why to use: Snappier attack on a sound makes it a bit more aggressive but is again, another way to induce drama and intensity in a melody.

Fermata: This is more about performance expression. In Ableton, you can extend the length of a note where a fermata occurs and perhaps automate a slight increase in volume or reverb. In VCV Rack, you might manually control the length of a note using a gate or hold module.

When and why to use: That’s an alternative way to bring

Portato: Combine the techniques of staccato and legato. In Ableton, this might mean programming MIDI notes with moderate length and slight overlap, and using a synth with a bit of glide. In VCV Rack, set up an envelope with a moderately fast decay and a bit of sustain, with a slight glide between notes.

Glissando: In Ableton, you can use pitch bend automation or a glide/portamento setting on a synthesizer. In VCV Rack, use a portamento or glide module, and create a sequence where the pitch CV smoothly transitions from one note to another.

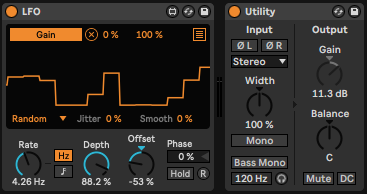

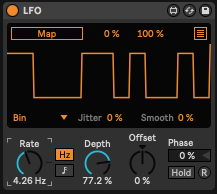

Trill: In Ableton, program rapid alternation between two MIDI notes. You might also use an arpeggiator set to a high rate. In VCV Rack, use a fast LFO or a sequencer to alternate between two pitches rapidly.

Exercises and Applications

- Experiment with Velocity: In both Ableton and VCV Rack, play around with the velocity of each note. Notice how changing the force behind a note alters the emotion and energy of your loop.

- Change Note Lengths: Experiment with shortening and lengthening notes within your loop. Observe how these changes affect the rhythm and flow.

- Use Automation for Dynamics: Automate volume, filters, or effects to add movement and life to your loops.

- Layer Different Articulations: Layer loops with different articulations. For instance, combine a staccato bassline with a legato lead melody.

- Play with Effects: Use reverb, delay, and modulation effects to enhance your articulations. A staccato note with a tail of reverb can create an entirely different feel.

- Morph Your Loops: Take a simple loop and create several variations, each with a different articulation style. This practice not only enhances your skills but also provides a plethora of material to work with. I do this as comping for effects but you can do this with midi notes as well.

By incorporating these articulations into your music production, even the simplest loops can blossom into complex, emotive

5. Random/Noise Wave: Chaotic and Experimental

5. Random/Noise Wave: Chaotic and Experimental As of my last knowledge update in September 2021, Ableton Live’s “Binary” form might refer to a specific device, feature, or concept that was introduced after that time. However, if we’re discussing a feature related to binary operations or manipulation, here’s a general explanation of how binary operations might be used in a music production context:

As of my last knowledge update in September 2021, Ableton Live’s “Binary” form might refer to a specific device, feature, or concept that was introduced after that time. However, if we’re discussing a feature related to binary operations or manipulation, here’s a general explanation of how binary operations might be used in a music production context: