VCV Rack Ideas And Meditations

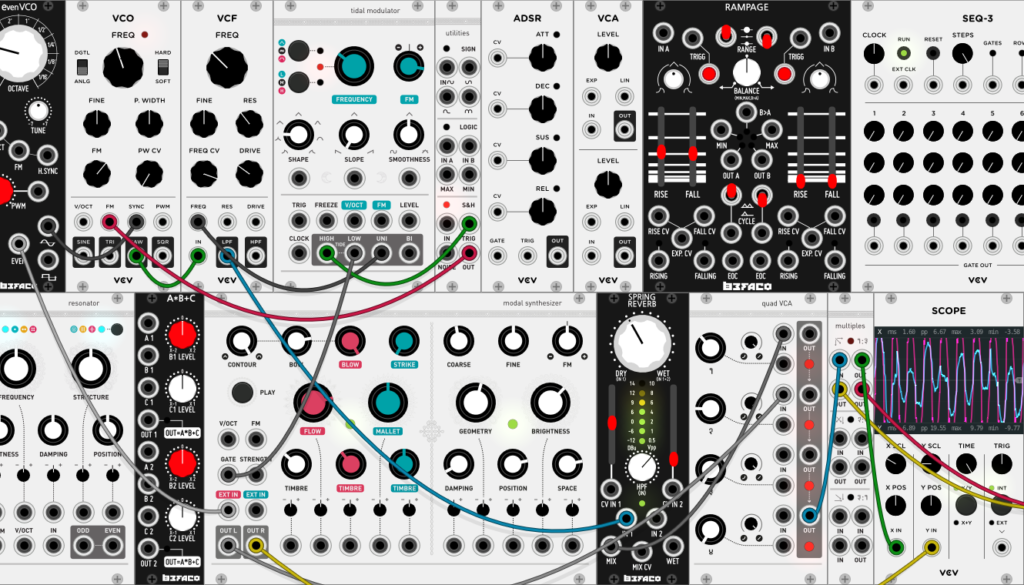

If you’re not familiar with VCV Rack you should be. While modular synthesis is an expensive hobby, usually reserved for people with cash flow, the open source, mostly free VCV rack is democratizing people’s access to this amazing creative tool. VCV Rack acts as a Eurorack DAW, allowing you to build complex patches using a variety of free, or premium modules, often based on existing hardware. In this post, I won’t talk so much about how to use VCV Rack, as there are tons of tutorials already on it. Instead I will talk more about how it has inspired me, VCV Rack ideas, and how you can use it to inspire yourself.

VCV Rack Ideas Are Meditative

The first benefit I noticed from VCV Rack was how meditative it is. I have been an avid practitioner of traditional meditation for many years now, and the similarities are striking. It forces me into a state of flow, one that often results in the dissolution of all outside distractions. A state where time and space become irrelevant, and I am concentrated on a singular purpose.

A lot of people conflate meditation with a silencing of thoughts, when that’s far from the truth. We’re human; we’ll never be able to silence our mind. Instead, we have to funnel those thoughts into a singularity. A singularity where you accept you have no control over what happens, both of which VCV Rack ideas do for me.

The Random Beauty Of VCV

That’s the beautiful thing about modular. These electrical circuits are so finicky that often what you aim to create and what comes out are often vastly different. It’s that sense of unpredictability that makes it so wonderful, and thus, meditative.

Surprisingly this sense of randomness and unpredictability isn’t lost in a digitalized version of modular. Somehow the community of open source developers have kept this aspect true to form, demonstrating the increasing dissolution between analog and digital as technology advances.

Many of you probably don’t know this, but I was an actor, before I was a musician, and even went to school for it. While you have a script, the fine art of acting was always in the slight improvisations. Lines often wouldn’t come out as intended, and you would have to react in the moment. This would often lead to beautiful accidents, far superior to the original script.

In a sense, the life that exists in modular is very much like a fellow actor on stage. It may have its lines, but ultimately, it will improvise, and it’s up to you to harness this improvisation and redirect it to something evolutionary.

VCV Rack Tutorials Are Fun

The second thing I noticed about VCV Rack was that it made me appreciate tutorials again. If you’ve been a power user of Ableton for as long as I have, you may find that Ableton tutorials an get super cookie cutter, and formulaic. This often results in stale music that sounds like everyone else who watched the same tutorial.

This may be one of the reasons why the sound we hear is becoming more and more homogenized, and less innovation is seeping through the cracks. This is despite an exponential increase in the number of musicians. However, with VCVRack, the tutorials seem more personalized. Even if you try to recreate something precisely, you’ll almost never get the same result, due to the nature of modular. The sheer amount of VCV Rack ideas you can get from these tutorials is incredibly exciting, and constantly motivating.

VCV Rack Tutorials Help You Build Existing Hardware

Another fun aspect of tutorials is that there are some people out there, like Omri Cohen, who build faithful reconstructions of existing pieces of hardware. The one that I linked to is for the Moog DFAM, a semi-modular percussive sequencer that allows you to build really wild, synthesized patterns.

Normally a DFAM runs for about $700 USD, which isn’t a small investment. While following these tutorials, you not only learn the ins and outs of the DFAM by building it piece by piece, but you also get to try it before you buy it, in a sense.

This allows you to figure out your setups and configurations for your hardware studio, without having to buy things, and send them back if they don’t fit. Also, since it’s fully modular, you can in theory connect multiple recreated devices together. This allows you to see how they will perform as a hardware version. So let’s say you wanted to see how a DFAM would interact with a Moog Subharmonicon. This is now possible through VCV Rack, for the low low cost of zero dollars. These are just some of the hardware VCV Rack ideas found in tutorials.

VCV Rack emulates the Moog DFAM

VCV Rack Changes How You Listen To Music

The third thing I learned while formulating VCV Rack ideas is that it changed how I listened to music. Normally I have a nerdy way of listening to music from a sound engineer point of view, where I analyzed EQ, compression, stereo spread, etc, but now when I listen I notice the changes in the patterns, and how things modulate.

While toying around with VCV Rack ideas, I start thinking about the patches that make the sounds. For instance, what waveform is controlling the FM, or how the envelope routes to the VCA. Or what hooks up to the clock, or how many VCOs are in play. Still, super nerdy, but it adds another dimension to the whole thing, which in turn, stimulate more VCV Rack ideas.

VCV Rack Ideas Help You Build Your Real Modular Setup

The fourth benefit I got from playing with VCV Rack ideas is that just like it allows you to build existing pieces of hardware to test in your setup, it also acts as a way to test modules for your real modular setup. There are a bunch of faithful emulations of existing modules. For instance, the Audible Instruments line is a software emulation of Mutable Instruments. There, you can get clones of things like their Clouds or Tides modules and test them in your setup.

Other examples include:

- Lateralus: Hybrid diode/transistor ladder. This models itself after the Roland filter circuit where they added a few alterations to get close to the Moog circuit.

- Vorg: Single segment of the filter circuit of Korg MS-20.

- Ferox: CMOS filter based on the circuit of the CGS749.

- Nurage: The Nurage bases itself on the circuit of Thomas White LPG which bases itself on the Buchla LPG.

- Vortex: this bases itself on the circuit of the Polivoks (Erica Synths version).

- Tangents: This bases itself on the Steiner-Parker version of Yusynth. The three models are variations of the same circuit.

- Stabile: based on the textbook Stave-Variable filter circuit (linear version).

- Unstabile: Nonlinear State-Variable filter with low voltage simulation

The real Mutable Instruments Elements

VCV Rack that includes Mutable Instruments emulations, aka Audible Instruments

VCV Rack Is Constantly Improving

Since it’s community supported, it’s constantly evolving, with new modules being added frequently. Most are free, too!

Some people will complain that it doesn’t integrate into other DAWs in a smooth fashion, but VCV has heard the complaints and in 2.0 the rumor is that they will have this integration.

These are just some of my observations about VCV Rack and its amazing ability to spark creativity. In truth, the sheer amount of VCV Rack ideas and inspirations you can get from those VCV Rack ideas are quite staggering. If you have any questions about it, or want to share your experiences with it, feel free to contact me, or make a post in Pheek’s Coaching Corner and let the community know what you think!

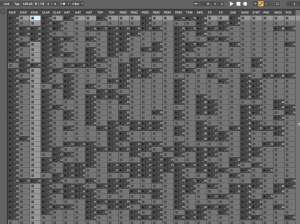

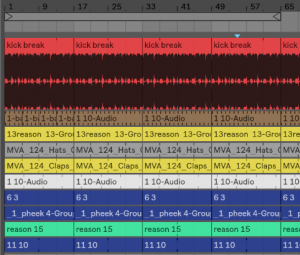

First, know your music. Whatever genres you listen to, please get to know what it has and needs. If you read this blog regularly, you know that I always insist on knowing and using references. The mothership method also starts with references. There are a few essential questions you need to ask yourself when you listen to your references:

First, know your music. Whatever genres you listen to, please get to know what it has and needs. If you read this blog regularly, you know that I always insist on knowing and using references. The mothership method also starts with references. There are a few essential questions you need to ask yourself when you listen to your references:

the organization.

the organization.