Changing Genres: Coming to Electronic Music from Other Genres

Since interest in electronic music really blossomed in terms of popularity, musicians from different spheres have all tried to capitalize on it. 20 years ago, big musicians in rock, pop, dabbled with it. We saw Madonna and some other bigger names venture into electronic sounds, but they sounded mostly like tourists in a country that they were visiting. With the recent victory of Billy Eillish at the Grammy’s for her album, not only it is mostly electronic, but it was also recorded in their modest home (precisely, in a bedroom) in Los Angeles. I’m currently involved in a few mixing engineer groups on Facebook, and while many were laughing at the album, some people took real interest in it—sometimes, less might be better, and you don’t need the latest toys to make something interesting.

Most newcomers to the scene, however, lack the knowledge of electronic music culture, and understanding of what electronic music is or sounds like. For people like me who have been listening to the genre for decades, when I hear someone with a rock background pick up synths and try to make techno, there’s something that always sounds slightly off: it doesn’t sound like what electronic is generally like, or it sounds something like rock, but not in a good way. In the 50s, people experimented with making classical music on synths—most of it was plainly horrible. Same goes for the early attempts of synth presets mimicking very colourful instruments like a trumpet. “Trumpet” presets make jazz musicians cringe, and with good reason.

Should an experienced musician restrain themselves from venturing into a new genre? Of course not. But knowing some tips to make the switch is probably the right course of action.

References and Getting to Know What Works

The biggest mistake I see from people who come to electronic music from a different scene, is not understanding who they are making music for. I can’t speak for how it works in the rock industry, but I think there are fewer fragmented areas of it than there are in electronic music. Electronic music has DJs, fans, labels, media, internet, etc., all with different sub-scenes. Knowing your specific audience can influence how you make music itself. For “musicians”, this is something many have a hard time getting their head around. For instance, if your track is made for DJs, you wouldn’t approach it the same way as if you make music for yourself, or for the general public.

“Why would I do it for DJs?”, a rocker once asked me.

Well, they expose your music to a public that might be interested to listen to it in a specific context. Your purpose is not the same as if you make music for, let’s say, home or even, after-parties.

“Oh, there are different types of DJs?”, he replied.

Yes indeed, I replied, and that’s another level of complexity in electronic music. You don’t make music for opening sets or after-parties, the way you would for peak time—and even for peak time, each genre has their own standards of what constitutes “peak music”. House, EDM (aka Vegas music), minimal, techno, etc., all have different styles. Even ambient and drone, have their own version of “peak time music”, which might sound bizarre if you’re not familiar with these genres, but go to an ambient or drone festival and you’ll know what I mean.

“But I just want to make cool music”, he then said.

Yeah, I know, I do too. But then again, if it’s for yourself and friends, you then know who you make it for and that’s very cool. If you’re aiming for a broader market and want to commercialize it, that approach probably won’t work well. Electronic music is a genre where you are free to do whatever you want and have unlimited resources to make many dream ideas come true, but the whole commercialization aspect of it is really messy, complicated, frustrating, paradoxical, and sometimes counter-productive. I’m aware this is the case in other genres as well, but the “successful” dance-oriented market is pretty tricky.

So what’s the real problem if you don’t follow a certain aesthetic?

Well, the most common scenario I see is enthusiastic people following their current tastes (often based on music that was cool 5-10 years ago) and without any self-criticism or feedback release music, and years later feel embarrassed about how off they sounded, or how badly it aged. Not a big problem, but it’s simple to not fall into this trap.

If you’re familiar with this blog, I frequently discuss the importance of references.

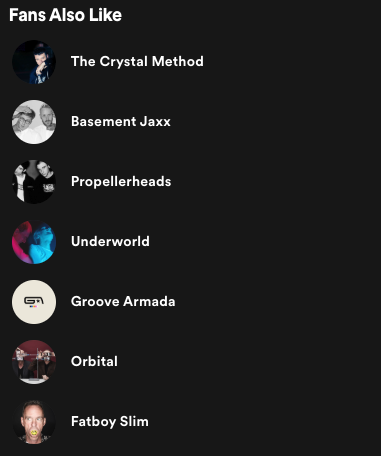

- One thing that might surprise you is that I often recommend Spotify as an exploration tool. Let’s say you like the Chemical Brothers… Spotify can expose you to similar sounding artists. You can also see the latest releases by an artist and how he or she has developed. Personally, I love that.

- Another thing I suggest is to spend some time listening to a lot of different artists. That also includes checking online magazines (I love XLR8R), get familiar with DJ charts, see what festivals book them or other artists you like, and get to know the other artists playing.

- Going out to events is important, too. To hear music in context really gives huge insights to a musician. As an engineer and coach, I occasionally pop in to local events to see what’s happening.

Collaboration, Mentoring, and Networking

I think another very important thing to do when you venture into other genres is to quickly find someone of reference or reputation that you can trust. Develop a relationship where there’s no filter on your discussions or feedback—this can take quite a while to find or build.

Working with friends who have great taste or hiring professionals also, for the most part, provides you with some quality control.

- Try to get to learn about plugins that are used on a daily basis by professionals.

- Have some ideas of where to buy quality presets for certain soft-synths for the purpose of learning how some sounds are made.

- Have a good idea of influential artists behind current trends. For every bigger, commercial trend, there’s a lesser-known artist who started a movement, an idea, or a musical direction that often “inspires” bigger names who commercialize it.

- Get familiar with festivals that are fun and that could be good hubs for networking.

- Build a network with media, promoters, and DJs. There are a lot of benefits and opportunities this type of network can produce.

However, when everything is said and done, collaboration is about making music, and getting to know the tips and tricks while networking. These are, in my opinion, some of the best things to know about if you aspire to make your way into a new genre!

SEE ALSO : Making and breaking genres in your music

Guerilla Marketing can be defined as a “low cost and sometimes disruptive marketing strategy to see the viability of an idea.” But mainly, it’s about doing something unusual to get attention. The best example I can share from my own experience would be one marketing blast I was part of in the early 2000s when Netlabels emerged, giving away music for free online and through any other possible channels. Giving away quality music was disruptive but also in tune with people who, back then, were also interested in getting music for free (note: it was in the golden age of music piracy and illegal downloads). In Montreal, in 2017, when it was said cannabis was going to be legalized, there was a guy who illegally opened four stores to sell it. He knew it was illegal and once it was shut down, everyone understood it was a publicity stunt for when it would be legal.

Guerilla Marketing can be defined as a “low cost and sometimes disruptive marketing strategy to see the viability of an idea.” But mainly, it’s about doing something unusual to get attention. The best example I can share from my own experience would be one marketing blast I was part of in the early 2000s when Netlabels emerged, giving away music for free online and through any other possible channels. Giving away quality music was disruptive but also in tune with people who, back then, were also interested in getting music for free (note: it was in the golden age of music piracy and illegal downloads). In Montreal, in 2017, when it was said cannabis was going to be legalized, there was a guy who illegally opened four stores to sell it. He knew it was illegal and once it was shut down, everyone understood it was a publicity stunt for when it would be legal. Another signpost I’ve used was a sort of music “target” I set through Ricardo Villalobos. I’d study his music, his sets, and a recurring question I had was “will he play this track of mine?” There wouldn’t be any goals attached to this besides, perhaps, having him play my music, but it was more as a reference point of how my music could be made or adapted,

Another signpost I’ve used was a sort of music “target” I set through Ricardo Villalobos. I’d study his music, his sets, and a recurring question I had was “will he play this track of mine?” There wouldn’t be any goals attached to this besides, perhaps, having him play my music, but it was more as a reference point of how my music could be made or adapted,