Generating Ideas and the Listener’s Attention Span

(photo credit Photo by Avi Richards on Unsplash)

There’s this zone where, as an artist, you’ll sometimes land where things are a bit confusing. It is precisely when you lose your perspective as if you’re doing music for yourself or for someone listening to your song.

There are multiple perspectives in music – one from the creator, the other from the listener. There’s something quite contradictory about music itself when you make it where you are performing music, it comes from you, your imagination, and current emotion but yet, musicians often also have someone else in mind when creating. That person you’re making music for isn’t there to provide feedback.

As someone who runs a Facebook group about coaching as well as a Patreon program where I train people, I face this situation over and over again with my students. They worry about their song being boring or that the listener will not finish the song until the end.

Is there a silver bullet to guarantee that everyone likes the song and will finish it to the end?

The quick answer is, no. You never can control how someone will perceive your music because you can listen to music at different times of the day and have different perceptions. It can be tied to the present emotion, where you listen to it, and what you were doing before, but the most disruptive thing will undoubtedly be the expectations the listener has.

However, all is not lost – there are some ways that can increase the probability that the person will enjoy the track thoroughly. In the article, we will go through a checklist of things you can do that can certainly help, technically, to have the listener more engaged.

Attention Is Competitive

I’d like to take a moment as well to point out that we’re living in an age of attention seeking and that has created a culture of wanting attention. This desire for attention is normal but you need to understand that people don’t have much on their hands. All social media platforms are hiring teams to pull as much attention from people like us so the attention span of everyone has dramatically dropped over time due to competition. The good news is that music can be a background experience – doesn’t stop you from doing other things while listening. You can still do your laundry, talk to friends, cook food, etc, while listening to music. This is exactly undivided attention, but when it comes to music, it’s just as good as any attention.

You Will Get Bored Of Your Songs (which leads to doubt)

One thing I see when people make music, they usually reach a point where they feel a bit lost. By lost, I mean that they might have certain doubts creeping on them. This happens mostly because people spend too much time working on their track, sometimes in a row (eg. extended session of 2h+) or they’ve been tweaking it for 3+ days in a row. If you’ve been following this blog, you’ll already know my thoughts on this: not spacing the time you spend on your track will most likely result in either not knowing if their idea can be understood or if it’s “good” anymore.

There are multiple phases in creativity, which is the initial where you have on your hands what seems to be a good idea, then you’ll try to put that in a story and last, you’ll try to make that into a timeline. Once you have these 3 initiated, you might circle between them over and over because the more you spend time on your song, the more you’ll hear things to fix and will feel the need to adjust something because well, you’ve been listening to the same idea for hours.

No one, except yourself, will listen to your song as much as you do.

This is exactly why you’ll doubt yourself. Because anyone who would be exposed to that much, would get bored or fed up of it. While in reality, there’s absolutely nothing wrong with it.

Don’t Fall Into Extremes

Now, when you make music, the balance of making music for yourself and or for others is something weird to find the sweet spot. If you, at one extreme, do music only for yourself, there is a good chance that it might be really messy and not reach out to anyone out there. But if you go to the other extreme and only make music for others, you’ll have no personality in there and be an empty shell. The right balance is understanding what works as a concept, then filling it with your ideas. In other words, what works is quite often the “same thing but different.”

You Have No Control Over The Listener

When it comes to the listener, you’ll have to accept that you have no control whatsoever over their tastes, attention span, mood, and availability. When anyone decides to listen to a song, they come from a specific need that is personal. Some will want something energetic for a task, others something smooth for relaxation, some who are DJs want music with a specific direction, others what in between for working/studying, etc. You can imagine that whoever will listen to your song, they will come with a specific need and it is also quite possible that the listener will be listening to your song along with a few before, and a few after. It’s not so often that you won’t listen to anything and then you listen suddenly to something and then nothing.

Now, let’s think about someone who has a playlist and has some new tracks to add, they’ll have pretty much the same approach as a DJ curating his next set. The music they keep is mostly something emotional and tainted by tastes. They either like or dislike. Because of how music is easily available nowadays, people will just quickly move on to the next thing because they can.

Now that we have all this in mind, let’s see what can be a deal breaker in how people can like or dislike your music.

How To Keep People Interested In Your Song

Here are ways to keep someone interested in your song:

- Mold a track upon a reference song that you know works. This one is the top because like anything in life, if you have a model of something that works, you can then replicate a concept. That works just as well for making a pizza as it does for a song. This was covered so many times in my Youtube videos but it’s basically about understanding the structure of the song, how sounds come in and out, levels, length, density, etc. Once you analyze the songs that you thought were amazing, you’ll realize that they are quite often simpler than you think.

- Make your music not too predictable but just enough to keep someone interested. What usually keeps someone interested is the feeling of feeling intelligent. This comes with the idea that they can predict what will happen next in a song either in terms of chord progression or arrangement-wise. If you anticipate it and it happens, it can really trigger some excitement. But what makes you hook is when it slightly takes you off guard. On one end, too much predictability will make it boring, but on the other end, too many surprises will create confusion and irritability. So usually you want the first part of your song to create a concept of understanding what the song is about, but then you bring new ideas. For a while, this is why breakdowns were so important because they were basically the gateway to the next evolution of the song but since they became so predictable, to me, breakdowns are irrelevant now.

- Have your music follow current trends but with slight novelty. I think any musician needs to spend some time every day listening to charts, new releases, what DJs play, and what people love. I find that quite often, I get ideas from the now and mix them with ideas from the past. I’ll listen to music from the 90s, hear an effect used in a way and then see how we can upgrade that old idea. Living completely in the past is not going to make your music feel fresh. But neither is being in the moment either, because you’ll either be lost in a sea of people making music like the trends or by the time your song is done, the trend is already old.

- Share something personal. This one is tricky but important. In music, ultimately, you want to be yourself. That comes with spending time crafting sound until you find something you really love. I like the idea that if you stop at the first few ideas, they might be shallow ideas but if you take your time, and go deeper, you’ll find more and more complex ones. If things are that deep, and you love it, then you’re entering the realm of originality and personal space. That zone is very vulnerable though because the more personal you get, the scarier it is to share it because rejection will feel very personal. But the good news is that people who will love that space will also be really in touch with who you are.

- Know who your music should reach and understand what they like. When you make music, you might follow a genre or not but if you do, try to understand what people like about it. Maybe you know it already. But mainly what makes someone skip a song are usually for the main few points: misalignment of their needs and what the song offers (ex. Songs has the wrong emotional tone or is technically overwhelming/underwhelming), clash of cultural sounds (ex. Song has a genre but is not respecting some basic concepts that might be irritating) or completely different tastes (tempo, tone, song key, production, sound use). Basically, being bold in what you love is encouraged but make sure it is also within certain limits of a genre, if you aim to be part of that direction.

Music techniques to find new ideas

Making music comes down to finding ideas. You can make music for years but a way to remain original is to have different ways to generate new ideas. Here are 3 main ideas that I use to generate ideas but there are so many others. Basically, you want, on one hand, to have original material and on the other hand, to find ways to process it. This means that you can have quality ideas that don’t need much cosmetics or have very generic ideas and add tons of processing. But both are 2 different ways which mean that you can create endless possibilities.

Creating new ideas can come, either from sampling/recording or generating synthetic ideas. I use quite a lot of randomization in my work because it is like a fast-forward from me fine tweaking. In other words, if I tweak a knob to find ideas it can take a while so instead, I use the computer’s power to come up with random tweaks, on multiple parameters, all at once which turns me into a curator of the best ideas coming out of that. Hitting the random button will give me in seconds, as many new ideas as the time I press that button. What’s powerful is that I can use every snapshot individually, and can also slowly morph between each snapshot, creating wonderful evolving ideas.

Randomize effects, modules, and macros.

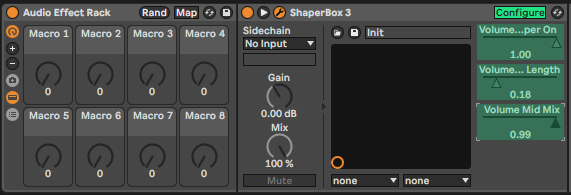

This is fairly easy in Ableton. You can use one or multiple plugins, then use command+G to group them together.

Then you can link parameters to macros.

For VST plugins, you’ll need to hit the configure button, then click on the parameters you want to use.

Once you have a bunch of parameters assigned to the macros knobs, you can hit that tiny rand button to see different random ideas.

I encourage you to save your rack with the snapshots you can also keep with the little camera button on the left. These saved are so practical when you want to call back some past ideas. Most of my most used VSTs are all saved as a macro for fast recalling.

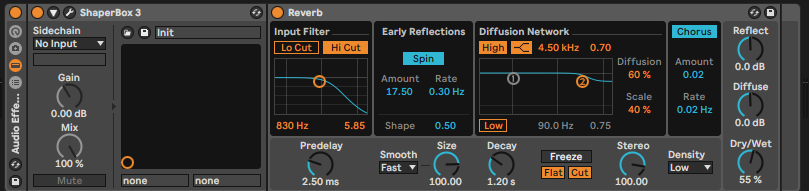

While we’re at it, the Shaperbox 3 is a HUGE game changer for me when it comes to sound design. You can do really, really crazy things with is and it’s also a swiss army knife for mixing, sound design, and even mastering.

Randomize Melodies

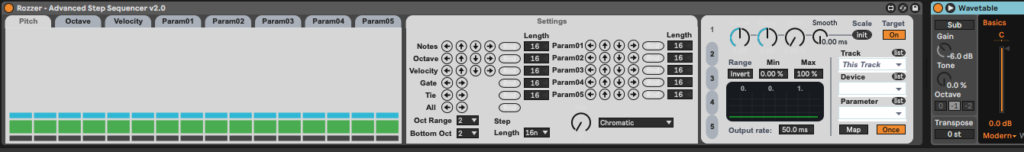

Randomizing melodies is another technique that I’ve been using for over 20 years. It’s been used in musique concrète and old early stages of electronic music. The quick way to do this is to use, for example, Rozzer. This is a free Max for Live patch that can generate ideas quite easily. Basically, you drop this on a MIDI channel, set a scale and root key, then hit random on the notes (it will generate a sequence of notes), then hit random on the Gates (which of these notes will play). That is a phrase that you can then tweak to taste or also you can explore polyrhythms by making the notes and the gate into different numbers (ex. Notes on a length of 12 and Gates, 7).

Sampling and resampling. This is also a fun technique. You can play a loop in your Ableton Live session and apply effects, then apply effects, but you record the whole playing around into a new clip.

Sampling and resampling. This is also a fun technique. You can play a loop in your Ableton Live session and apply effects, then apply effects, but you record the whole playing around into a new clip.

From the recorded clip, I can then chop, reshape, reprocess, stretch etc. That is called resampling and it is a very powerful way to transform ideas. I like to say that resampling clips are generational. So a sound processed once is the first generation, then if you reprocess that clip is second, and so on. When I use sounds for my music, I usually go with sounds that are 4-5th generations. They are usually richer.

I hope this helps.