Creating a music sketch

In this post, I’d like to explain how making a music sketch can help you to stay on track when creating a song or track, much like how a painter creates an initial sketch of his/her subject. I’ve explained in previous posts that the traditional way of making music goes something like this:

- Record and assemble sounds to work from.

- Find your motif.

- Make and edit the arrangements.

- Mix.

Here we’re talking about a way of making music that was popularized in the 1960s and is still used frequently today. But what happens when you have the ability to do everything yourself, and from your computer alone? Can you successfully tackle all of these tasks simultaneously?

When I do workshops, process and workflow are generally questionable topics to address because everyone has different point of view and way of working. However, to me it always comes down to one thing—how productive and satisfied an artist is with his or her finished work. Satisfaction is pretty much the only thing that matters, but I often see people struggle with their workflow, mostly because they keep juggling between different stages of music-making and get lost in the process (sometimes even losing their original idea altogether). For example, an artist might start working with an initial idea, but then get lost in sound design, which then leads them to working on mixing, and then sooner or later the original idea doesn’t feel right anymore. For some people, perhaps its better to do things one at a time; the old before-the-personal-computer way still works. But what if breaking your workflow into distinct stages still doesn’t work? Is there another alternative approach?

In working with different artists and making music myself, I’ve come to a different approach: creating a music sketch—a take on the classic stage-based process I just mentioned. Recently, this approach has been giving me a lot of good results—I’d like to discuss it so you can try it yourself.

Sketching your songs and designs

I completed many drawing classes in college because I was studying art. If you observe a teacher or professional painter working, you’ll see that when they create a realistic painting of a subject, they’ll use a pencil first and sketch it out, doodling lines within a wire-frame to get an idea of where things are. Sketching is a good way to keep perspective in mind, and to get an idea of framing and composition. The same sketching process can be used in music-making.

When I have an idea, I like to sketch out a “ghost arrangement”. Sometimes I even sketch out some sound design. The trap a lot of people fall into when making a song—particularly in electronic music—is to strive to create a perfect loop right from the start. Some people get lost in the process easily which is, honestly, really not important. People work on a “perfect loop” endlessly in the early stages of making a song because when you are just starting a song, the loop will have no context and it will be much more difficult to create something satisfying. By quickly giving your loop a context through a sketch-type process by arranging or giving the project a bit more direction, you’ll hear what’s wrong or missing.

I’m of the belief that having something half-done as you’re working can be acceptable instead of constantly striving for perfection. I think this way because I know I’ll revisit a song many times, tweaking it a little more each time.

Sketching a song can be done by understanding at the beginning of the process that you’ll work through stages of music-making more quickly and roughly, knowing you’ll fix things later on. This is more in line with how life actually goes: we live our lives knowing some problems will get solved over time, and that there are many things we don’t know at a particular moment in time. In making music, some people become crazy control freaks, wanting to own every single detail, leading them down rabbit hole of perfectionist stagnation, in my opinion.

Creating a sketch in a project is simple. Since I work with a lot of sound design, I usually pick something that strikes a chord in me…awakens an emotion somehow. Since this will be my main idea, next I’ll try to decide how it will be use as a phrase in my song. In order to get that structured, I need to know how the main percussion will go, so I’ll drop-in a favourite kick (usually a plain 808) and a snare/clap. These two simple, percussive sounds are intentionally generic because I will swap them out during the mixing process. You want just a kick in there to have an idea of the rhythm, and the snare clarifies the swing/groove.

Why are the basic kick and snare swapped out later?

I swap out the snare and kick later because I find that I need my whole song to be really clear before I can decide on the exact tone of a kick. A kick can dramatically change the whole perspective of a song, depending on how it’s made. Same thing goes for a snare—it’s rare I’ll change the actual timing of the samples, but the sound itself pretty much always changes down the line.

For the rest of the percussion, I’ll sketch out a groove with random sounds that may or may not change later on, but I use sounds I know are not the core of my song.

With bass, I usually work the same way; I have notes that support the main idea but the design/tone of the bass itself has room to be tweaked later.

As for arrangements, when creating a music sketch I will make a general structure as to what goes where, when some sounds should start playing or end, and will have the conclusion roughly established.

Design and tweak

Tweaking is where magic happens—this is where, in fact, a lot of people usually start their music-writing process. Tweaking and designing is a phase where you clarify your main idea by creating context. I usually work around the middle part of the song; the heart of the idea, then work on the main idea’s sound design. I layer the main idea with details, add movement and velocity changes.

- Layering can be done by duplicating the channel a few times and EQing the sub-channels differently. Group them and add a few empty channels where you can add more sounds at lower volume.

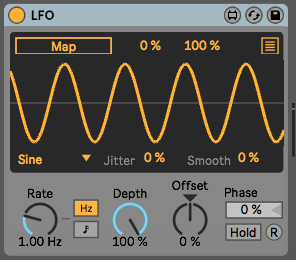

- Movement can imply changes in the length of the sound’s duration (I recommend Gatekeeper for quick ideas), panning (PanShaper 2 is great), frequency filtering, and volume changes (Check mVibratoMB for great volume modulation). The other option is to add effects such as chorus, flanger, phaser, that modulate with a speed adjustment. Some really great modulators would be the mFlangerMB (because you can pick which frequency range to affect—I use this for high pitched sounds), chorus (mChorusMB) to open the mids, and phasers (Phasor Snapin) for short length sounds. Another precious tool is the LFO by XFER—basically you want the plugin to have a wet/dry option and keep it at a pretty low wet signal.

- Groove/swing. This is something I usually do later—I find that adjusting it in the last stretch of sketching provides the best results. The compression might need to be tweaked a bit, but in general the groove becomes much easier to fix once everything is in place.

- Manual automation. Engineers will tell you that the best compression is done by hand, and compressors are there for fast tweaks that you can’t do. Same for automation, I find that to be able to make your transition and movement using a MIDI controller is a really nice finishing touch that is perfect in this stage.

Basically, the rule of finalizing design is that whatever was there as a sketch has to be tweaked, one sound/channel at a time. Don’t leave anything unattended—this can manifest from a fear of “messing things up”.

When tweaking specific sounds from the original sketch, you should either swap out the original sound completely, or layer it somehow to polish it. I always recommend layering before swapping. I find that fat, thick samples are always the combination of 3 sounds, which make it sound rich. When I work on mixing or arrangements for my clients and I see the clap being a single, simple layer, I have to work on it much more using compression, sometimes doubling the sample itself, which in the end, gives it a new presence. Doubling a sound—or even tripling it—gives you a lot more options. For example, if you modulate the gain of only one of the doubles, you not only make the sound thicker but also give it movement and variation.

All this said, I would recommend making sure your arrangements are solid before spending a lot of time in design. Once you start designing, if your arrangements have a certain structure, you’ll be able to design your song and sounds specifically according to each section (eg. intro, middle, chorus, outro) which gives your song even more personality. Sound design completed after a good sketch can be very impactful when the conditions are right.

Try sketching your own song and let me know how it goes!

SEE ALSO : Creating Timeless Music

basslines. If that’s not enough you can also use the midi effect velocity which can not only alter the velocity of each note, but in Ableton Live it also has a randomizer which can be used to create a humanizing factor. Another way to add dynamics is to use a tremolo effect on a sound and keep it either synchronized, or not. The tremolo effect also affects the volume, and is another way of creating custom made grooves. I also personally like to create very subtle arrangement changes on the volume envelope or gain which keeps the sound always moving.

basslines. If that’s not enough you can also use the midi effect velocity which can not only alter the velocity of each note, but in Ableton Live it also has a randomizer which can be used to create a humanizing factor. Another way to add dynamics is to use a tremolo effect on a sound and keep it either synchronized, or not. The tremolo effect also affects the volume, and is another way of creating custom made grooves. I also personally like to create very subtle arrangement changes on the volume envelope or gain which keeps the sound always moving. modulate anything, and they will automatically create movement. For each LFO, I often use another LFO to modulate its speed so that you can get a true feeling of non-redundancy.

modulate anything, and they will automatically create movement. For each LFO, I often use another LFO to modulate its speed so that you can get a true feeling of non-redundancy. A sound’s position in a pattern can change slightly throughout a song to create feelings of movement; a point people often overlook. This effect is easier to create if you convert all of your audio clips to midi. In midi mode you can use humanizer plugins to constantly modify the timing of each note. You can also do that manually if you are a little bit more into detail editing but in the end a humanizer can do the same while also creating some unexpected ideas that could be good. Another trick is to use a stutter effect in parallel mode to throw a few curve balls into the timing of a sound every now and then.

A sound’s position in a pattern can change slightly throughout a song to create feelings of movement; a point people often overlook. This effect is easier to create if you convert all of your audio clips to midi. In midi mode you can use humanizer plugins to constantly modify the timing of each note. You can also do that manually if you are a little bit more into detail editing but in the end a humanizer can do the same while also creating some unexpected ideas that could be good. Another trick is to use a stutter effect in parallel mode to throw a few curve balls into the timing of a sound every now and then.