This has been a popular topic recently—I think that because of the pandemic and the isolation that comes with it, people rely a lot on online contacts to get feedback on their music. The lack of in-person music testing as well as and lack of being able to go to clubs has changed the way we are able to analyze our own music.

I was a part of an organized live stream recently to support a friend named Denis Kaznacheev, who has been held in prison for something we all think is impossible (but that’s another topic). Being in a room with 4 people, playing live, and getting feedback after months of isolation was a weird experience. The first thing that came to my mind was, that my music sucked. Yeah, I also go through it once in a while, and I had forgotten how playing music for and in front of people changes the dynamic of a song. In studio, it sounds a specific way but add one listener and it’s all of a sudden, different.

Some song, different context, completely different mood. Was there something I could do to predict this?

Technically, there was absolutely nothing wrong with what I did. People who tuned in loved it. The thing that clashed was the mood, the feel of the track, compared to what I had in mind. In past articles I’ve discussed the importance of a reference track, and this could have helped me in this particular situation, and could have helped better classify my music as well. But as you know, there’s no do-it-all plugin that can prevent this. This is why many people struggle with judging their own music.

Technical Validation

When it comes to technical items, you can self-validate using some handy tools.

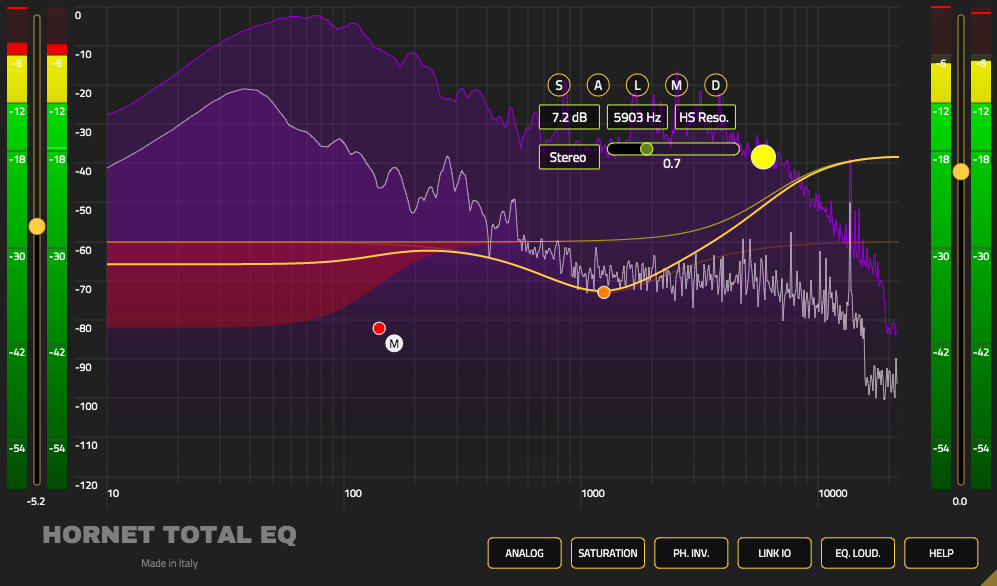

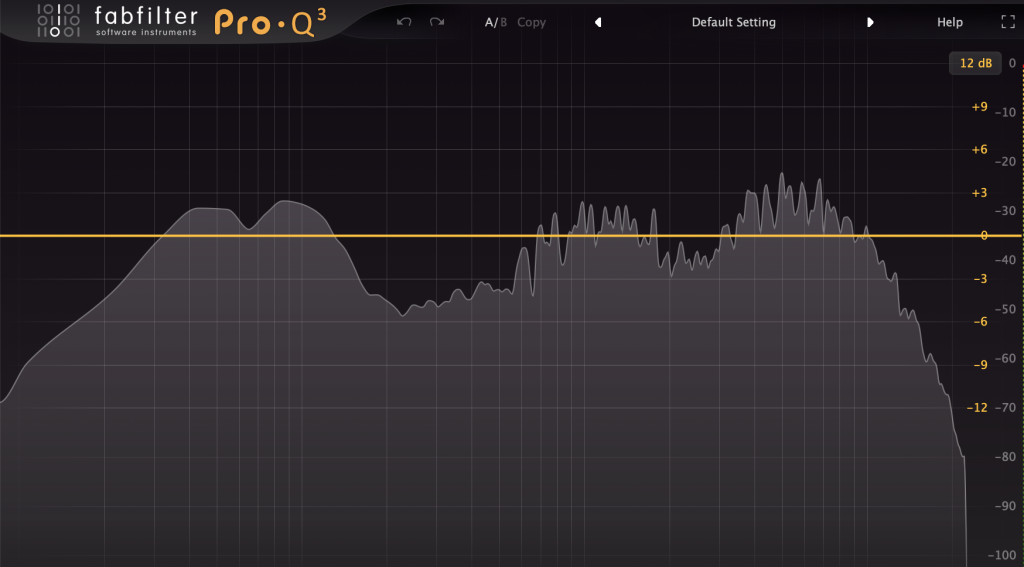

See if your track is, compared to a reference, feeling like the same tone and balanced, I’d recommend using Reference. This tool is my go-to plugin whenever a client insists that the track I’m working on doesn’t sound like a particular song. I’ll load up the reference song and then, after volume matching, I can see if the lows, mids, highs are adjusted in a similar way than my mix. It also shows you if you have, per band, the same level of compression or wideness. It doesn’t lie and you can match it to have something similar. But how do you raise one band to match the reference?

I use a multi-band compressor to compress and, or EQ. A shelving EQ, with 3 bands can be helpful to adjust, but a multi-band compressor really can set the tone. You’ll set the crossovers of each band to match Reference and by adjusting, you’ll see it react to your gain or reduction. While you could use any multi-band compressors, I’d highly recommend the Fabfilter MB.

The same company that makes Reference also made a plugin named Mixroom which, with the same idea as reference, focuses on everything in the mids and highs. It’s a bit tricky to use at first, but once I found reference songs that were analyzed properly, it gave me some interesting pointers on what to push or remove. I thought it was pretty interesting to reverse-engineer some complicated mixes.

Many times people will tell me they don’t like to compare to anyone or that they’re going for their own style but that’s like trying to draw your grandmother from your memory. Some people might do better than others, but audio is abstract and you need to compare yourself to someone else to know what’s lacking or overflowing. I mean, even within a mix, I compare my channels to see their peaks, densities, and panning to make sure one doesn’t cross another, unless to create something as a whole.

People struggle with loudness, but it’s is a bit easier to manage. You’ll need a metering tool such as the IKmultimedia TR5 Metering or the lovely Hawkeye from Plugin Alliance. They are costly but necessary. For a mix, you have to keep in mind a few details: the loudest peak should be -6dB, the RMS (more or less the density) around -13 to -20dB, in LUFS, I’d suggest to be around -15dB and dynamic range to be above 10. A plugin such as Reference will also indicate loudness, and that can be really useful to see if you’re in the same ballpark.

Please consider these are numbers I deal with, and that for certain genres, it can be completely different.

If you come to struggle with the low end, the guys from Mastering The Mix also have a low-end validation/enhancement with the excellent Bassroom plugin. Again, you’ll need a quality reference to do the trick, but once loaded and with some practice, a muddy, weak low end will be a thing of the the past.

These are the best technical validation tools I’ve used in the last few years. They’re efficient, affordable and very useful in whatever I do.

Self-Mastering and Mixing

Pretty much anyone who’s been making music for a while or has studied audio engineering will agree that mixing or mastering yourself isn’t the real deal. It’s doable, understand me right, but you’re not winning. With the previous listing of all the technical tools I shared, you can make some really efficient mixes, but perhaps sometimes that’s not enough.

As an engineer, the main thing I’ll say is that someone else might spot things that are in your blind spots, plus that person is also emotionally detached from the music itself, so making decisions feels like less of a risk in itself. If you’ve been reading this blog regularly, you know I often refer to our duality as humans to have a analytical side and a creative side. When I work with musicians, I invite them to see this duality as a muscle. Your creative side needs to be exercised; it needs to constantly be fed because it’s a sponge. You want to find the perfect routine and be efficient at it, then break it to pieces to reinvent your new way of making music by re-combining them for a new version of yourself.

The way I see music-making isn’t about trying to be in full possession of your potential, but more about always putting yourself into a state of instability and risk, so new creative ideas emerge. You’ll connect the dots of the past to create a path in the now.

This state of mind is one that is not always technical, and it’s raw. I would invite you not to tame it, but to create spontaneous ideas and raw projects.

This approach is basically the exact opposite of sitting in front of your computer to design and fix a snare. There’s nothing wrong with that if you like, it but like I say to people, artists should become experts at flow, not perfection. They want to be artists, not craftsmen. But I won’t stop you from being both—I just often feel that technical production doesn’t age as well as solid creative ideas. The only thing that stands the test of time is simplicity, and that comes with a mastery of both flow and technical expertise.

If you want to be a master at everything, you’ll be very average at everything as well for quite some time, or potentially forever.

So, imagine you have an amazing idea that you made but you are very average at mixing and new to mastering—you’ll probably be butchering your idea when you try to do either. Yes, you save money and learn by doing it yourself, but I think if you’re aspiring to release something on a good label, to get attention, it might be a good thing to have someone look into your mix, even a friend. But if you really want to do it all yourself, get yourself solid tools to make sure you get the most out of them.

If you want to practice mixing, I suggest trying to find what I call, a swap buddy who can send you their mixes and vice-versa. You both learn by tweaking each other’s work, and going back to your own music after will feel easier, and clearer as well.

Psychological Validation

Now, psychology is an area where don’t get any tools to help that we all have to deal with. It’s that limbo where you maybe made a few different mixes and feel unsure which one is best. You know technically everything is there and in order, but in the last bit you’ll try to label your song into one of these buckets: Good, Not Good, Still needs work, Ready for mastering…etc.

Are advanced, experienced, and veteran producers exempt from this state of mind? Not at all. After decades of making music, I still have no idea if my music is “good” or not, even if got in the top 10 on Beatport or if my friends all love it. Deep inside, sometimes, I’ll doubt myself. However, I came up with some personal rules to help me judge if I think my own work is decent or not.

Deal with technical points first: This is why I started this post with technical stuff. I see in our Facebook group, people giving feedback, and my observation is that it is often biased by their mood or listening situation. What has become clear to me is that when giving feedback, you need a common reference. I can tell you that your kick is too loud, but compared to what? I have clients sometimes who complain about the low end being overpowering but in the same mastering session on that day I had another client who loved really, really loud kicks. The difference was laughable and both had the exact opposite feedback: one had weak low end but he felt it was too much while the opposite was a bass orgy but he wanted more. Could it just be what they hear? Yes, probably, and this is why you need to be able to use a FFT to check, but also, listen to you music in the middle of a playlist that has other songs of the same genre to know if it sounds right.

A client was telling me “It sounds right in the studio, wrong in the car and at home, its a different song… which one is right?”

The one that is right should be your studio version, but it should be cross-validated technically with other songs. If it doesn’t sound right at home, then find a song that sounds good there and then study it at the studio to see what that song has that yours don’t.

Know that you’ll never really have a permanent opinion about your music. Each day your mood might change and affect how you appreciate your music. Down the road, you’ll learn new techniques and then hear mistakes in your song, you’ll hear a better song than yours… all these points will make you doubt yourself. You’ll always want to go fix something. Since you know you’ll never be really satisfied with it, then you can accept to move on faster. Just start another song, apply what you learned, use your new influences and try something new.

Nothing exterior will validate your music. No matter what you think or do with your song, you might doubt it. This means, you don’t need the latest synth or to be on that specific label. “...and then I’ll be happy.” is a fallacy. Knowing that, it re-centres you to count on a handful of friends for feedback.

4. Let things age. Nothing better than taking a few weeks off before listening to know how you feel about it.

What’s interesting is that, whenever I receive criticism, I start see a perspective I didn’t look into enough—super important. Music production and audio engineering is often discouraging and that’s the reality of the art. That said, I don’t think there’s a day where I make music that I don’t learn something new. Accept that everything is work in progress. This is why songs that take too long to finish are often because my perfectionist side took over, and that’s not where I can make magic happen—it’s often the other way around.