Stuck on a Song? Tips to Help You Overcome Negative Thought Patterns

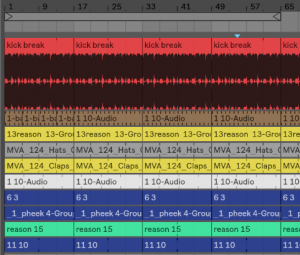

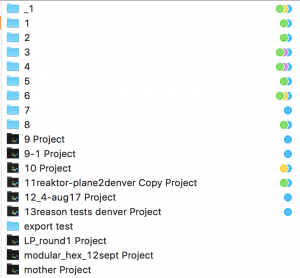

One of the best things I’ve ever done has been a challenge I signed up for in early 2020 to make one song per week for the entire year. It felt a bit like wishful thinking at the time knowing how busy I am; I didn’t think I’d be able to pull it off, but it’s turned out to be one of the best exercises I’ve ever done. The most important lesson for me was learning that writer’s block comes and goes, but being stuck on a particular song seems like it happens more frequently. The more you make music, the more you develop personal strategies to overcome this problem quickly. My experience making one song per week has been extremely useful when working with younger artists, as I quickly spot where they’re stuck and can help them see options they’re not seeing.

I made myself a list of rules and tricks to refer back to when I get stuck on a song and noticed they usually stemmed from two categories: technical issues, and mindset. Rethinking your mindset helps re-frame what the problem is, exactly—but that’s usually the hardest part of overcoming issues finishing a song.

The trick, as an artist, is to quickly spot in which of those two categories of problems you’re facing, and then find a solution. Let’s discuss some of the most common problems that makes people get stuck on a song:

“I don’t know where to start.”

Category: Technical Issue & Mindset

This thought pattern can also be re-framed as: I lack material to start using, I have difficulty translating my ideas into software, or I lack motivation.

This is a fundamental question that, even with experience, many artists sometimes still have. The thought of starting something new can be overwhelming. Coming into a new session with tons of motivation and ideas doesn’t overcome the very first hurdle you face when starting a new project: how to get it done, and of course, how to get started.

My first recommendation is to take a Kaizen approach (a Japanese project management methodology) and first think about what you want to do, and then start with the first thing you know about it. For example, if you are making a house track, maybe you know you’ll want a 4/4 kick as a loop, so start with that, then add a few other elements. Maybe it won’t be the right sound exactly, but just start with that. Can’t make a loop? Get pre-made loops, slice them, and rearrange them to taste, and have that as your starting point.

For productivity’s sake, use sounds you find, don’t chase something you have in mind. Find one that you like and then play with it to see what you can make out of it. Break your project down to things you know you can do, as this will bring self-confidence before tackling tasks that are difficult to do.

Is there a right way to start a song? No. Each song can be started in multiple ways. But capturing yourself jamming with loops and sounds is about yourself being “in the moment”, and that is very much what music is about.

If you’re overwhelmed by a lack of resources, I’d encourage you investing into LoopcloudLoopcloud. It’s a quick-fix solution to gather samples based on what you need, instead of buying bundles. It’s also an incredible option to find that missing link, as you can open it in your project, sync it to your DAW and play samples in context to see how things fit. Using samples is, for me, a hip-hop inspired approach that never fails. It’s also a way of layering different sounds to create something new. When I’m lost, I go back to sampling.

“I don’t feel motivated to make music.”

Category: Mindset

This thought pattern can also be re-framed as: I don’t see why I’m doing this, or I lack an idea of where this will go.

One of the reasons why people are obsessed with releasing their music comes with the fact that their efforts are now validated. A lot of artists are goal-oriented, others are more interested in the journey. As life goes on, you might find you’re more one or the other. If you lack motivation, it’s possible you lost track of priorities. Maybe you need to have a goal in mind? Or perhaps you need to be exploring a new technique?

Knowing your needs, you can reorganize your music sessions accordingly. If it’s because you don’t have labels to send your music to, perhaps you can focus on podcasts or DJs. If you need new ideas, I suggest you check YouTube and look for a technique, either new or something else.

I’m a firm believer that I get better results by seeing each song as a lesson, an experiment, something to learn…instead of seeing it as something to be controlled or perfected.

Every time I find myself in front of someone who lacks motivation, I try to bring them back to what makes them happy and encourage them to get back to what works, what brings them joy. Do that for a while, and prepare material for when the inspiration returns.

“My sounds (or anything I use) don’t feel as solid or as cool as my references”

Category: Mindset

This thought pattern can also be re-framed as: I lack the technical knowledge to achieve something similar to artists I like.

Comparing yourself is nothing new or uncommon; we all do it. Where it fails is, when you compare yourself with people who are not in your league. It’s like playing football and complaining you’re not able to play like Ronaldo or other pros. Your friends would start laughing, right?

How is that any different than comparing yourself to artists who has a lot more experience? You’re seeing a song but you don’t see the 30 other songs they did before nailing that one. Do you need to be a pro to enjoy playing a sport? No. It should be the same for music.

If you keep in mind that each song you make is a lesson, then making 20-30 songs will teach you a lot. On the 50th, you’ll have a vocabulary and fluidity to express yourself with a lot more ease. After this, you can slowly look to others to pick up tricks, inspirations, or ideas.

“After a while, I lose interest in what I do.”

Category: Technical

This thought pattern can also be re-framed as: Listening to my song for too long bores me.

Welcome to music production! If you only work on one song, you’ll get fed up with it quickly. The idea of working on a song is that it’s something you want to finish quickly so you don’t lose sight of your initial idea, but you want to take your time to fix the issues. I usually wrap a song and then I’ll come back to it in sprints of 30 minutes to an hour (max) to fix as many issues as I can, but then I’ll close it and do something else. I never get bored and the distance I take between sessions keeps my judgment fresh. As you might have already read, I’ve encouraged musicians to make multiple songs at once to not get bored in this blog many times before.

I have more and more clients that come to me being frustrated with their first song. Usually, this is normal. A large part of my songs don’t feel right, but I need to move on. Moving on is an important habit to learn, I find.

“My song feels boring because of getting too technical.”

Category: Technical

This thought pattern can also be re-framed as: I tend to over-analyze what I do to the point where I get lost.

Technical tweaks often kill the beauty of spontaneous creativity—I try to find a balance between the two. Sometimes, I ask friends to take care of the technical part of certain songs I don’t want to ruin the rawness of. The thing that makes it boring, is that you have been over-hearing it. To think that anyone would listen as much as yourself, or that someone would analyze your song as much as you do after 100 listens, is highly misleading. Again, this comes down to taking a lot of breaks and working on multiple songs at once.

“Mid point in the song, I don’t know what to do next.”

Category: Technical

This thought pattern can also be re-framed as: I struggle to make the story-line evolve properly.

Having a loop is one thing, but keeping it interesting is another. Many people make the mistake of starting a song by at the beginning, thinking their loop is the starting point, but I like to think of putting the main loop you’ve been working on, right in the middle of the song. Then I deconstruct it by simplifying it from the beginning. You can then add elements to create the last stretch of your song.

Usually when you’re at the mid-point, most of the song’s main work has been done and you can process your elements to create “child” ideas that you can use as supporting elements, which will help a song carry on until the end.

I usually start working on the main part of the song as well as what follows so I have a better idea of the song’s core. Creating the intro and conclusion ends up being a piece of cake. This usually solves this issue of now knowing what to do in the middle.

Now the other technique is also to give variation to your main idea. The fastest way to do that is to slice it and then change the order, either randomly or by hand, depending of your style.

“I’m lacking ideas on what to add to my song, is it enough?”

Category: Technical

This thought pattern can also be re-framed as: My song needs validation.

I always like to start with the premise that my song is enough, and that if something seems to be lacking, it could simply be because I’m not exploiting enough what I have already. Less is more, is the school I come from, and I’ve made tracks with three sounds alone, which was probably the most useful exercise ever, as well as an eye opener for creative use on whatever I had already. If someone playing the hand drum can make a song out of it or if a pianist can write an album, you can do a song with what you have already.

Now, if you say something is missing compared to… that’s another story. The best way to validate your work is to load up the reference and to A/B. The first question is, do they have the same amount of sounds used? Take the time to count them, you’d be surprised sometimes that you might have more than your references. Sometimes, what’s missing is just a good mix, a reverb, or modulations.

“I don’t know how to create a new idea that I’ve never made before.”

Category: Technical

If you’ve made 20 songs, at some point you might run out of ideas. If that’s the case, there are a few quick things you can do to get your inspiration back. I’m not talking about having a writer’s block here.

The first thing I encourage people to do to find new ideas is the “talking out loud, describing what you hear” method. I’m not sure if I’ve shared this idea before, but it’s fairly simple. The way I use it is to check a random song, either in my Soundcloud feed or Spotify, or whatever you use to be exposed to music you haven’t heard before. Play it, and then, using your smartphone, record some vocal notes of you describing your best what you hear. Try to do it for the duration of the song and when it’s done, stop the annotation. I like to have a bunch of tracks described like that and have vocal notes without any references to what I have listened to. When you eventually listen to your notes, it will be very abstract ideas of songs you can listen to. You can also do this throughout the day—some people think about making music all day and don’t know how to vent, so I suggest to record all the ideas they have, vocally.

This method came to me as I was waking up during the night with ideas and I would record a description of my dream. I would later listen to them and have a lot of concepts.

The other way to get a lot of ideas is to use songs or samples and chop them into random ideas. This sometimes will generate an idea that you can extrapolate by pulling out the best of it.

“I don’t feel satisfied with my mixes.”

Category: Mindset

This thought pattern can also be re-framed as: I feel technically inadequate.

This one’s a bit complicated. First and foremost, the idea of a perfect mix is counter-productive because such thing doesn’t exist, or at least, for the person who mixes it doesn’t. There’s always something to fix and at one point, you need to wrap it up and call it done, even with imperfections. What’s left undone, unless it’s a huge issue (which are usually hard to miss), will often be seen as something that is part of the song. People who are looking for the flaws of your song are rare. Usually someone will like or dislike it. This is why very few people care for details. People have small attention spans, and those who really see the issues, aren’t the people you’re making music for.

The idea that each song is a lesson also applies to mixing. You bring your song to the max you can bring it to. I like to have my mixing sessions in three rounds: the first, I remove all issues. The second, I work on embellishments. Third, I do the final adjustments and fix the tone.

You can’t fix everything effectively in one session so it’s always a good thing to take a second look after a night of rest.

“I don’t know how to finish a song.”

Category: Technical

Finishing music is a hot topic. It’s a good thing to know but it’s not a prerequisite to enjoy making music. Some people have a lot of fun jamming or starting loops and that’s it. The idea that you have to finish a song and potentially release it is, what I call, a romantic idea, and just like any romance, it’s not a necessity. Some beautiful relationships exist without romance. I find it way more important to collect ideas, create sketches, and make loops in large quantities. Eventually, when you get to finishing songs, if you have all those ideas and loops ready, it will feel like you have a gold mine.

Learning to finish songs is a skill that comes with using references, as I’ve explained many times in this blog. You use one song, check how it’s made, then apply part of the template to a loop you have. That’ll do it. Really, it’s that’s simple; it’ll feel like cheating.

I hope this was helpful in your day-to-day struggle!

the organization.

the organization.

Filtering ideas into a concept

Filtering ideas into a concept In many ways, the overwhelming amount of content we’re exposed nowadays can make us lose track of what’s going on. Musicians can post a track the second after finishing it, and the whole world can potentially hear it within minutes. Yet the tidal wave of self-released music is so frequent that it can also be harder than ever to get noticed. If you’re attentive and curious, you can catch people’s new ideas, yet the question now is – how can one really can keep up?

In many ways, the overwhelming amount of content we’re exposed nowadays can make us lose track of what’s going on. Musicians can post a track the second after finishing it, and the whole world can potentially hear it within minutes. Yet the tidal wave of self-released music is so frequent that it can also be harder than ever to get noticed. If you’re attentive and curious, you can catch people’s new ideas, yet the question now is – how can one really can keep up?