Falling Out of Trends

Is chasing music production trends based on a genre a lost cause?

Working with clients teaches me every day how people cope with the music business and their ongoing challenges with their music-making. One is how an artist’s relationship with genres changes over time. Their tastes change, and so are the music production trends. Think of your favourite artist or DJ, performer that you’ve been following for more than 10 years, you’ll rarely see them follow a linear development and stick to an aesthetic or genre. Over time, artists tend to explore, be curious, be influenced, and change. So are their tastes.

Perhaps your tastes didn’t follow your favourite producer. Maybe they got too adventurous for your tastes, or possibly you felt let down by a lack of originality. In any case, it’s normal to think we grow apart, primarily because of what we are exposed to: some ideas grow on us while others eventually feel boring. But some manage to go through time and still grab our attention, which happens, but it might be a bit rarer.

When a genre gets out of fashion or becomes overpopular, some might drop out, feeling fatigue or perhaps feeling disconnected from what the music comes down to. Some genres last around 10 years and then go dormant or become less popular for about the same time (everything is cyclical), so is making music based on a genre a dead end?

For some producers, understanding and mastering a genre can take years to make music that sounds like their references. By the time one feels comfortable with their output, the aesthetic might feel old. Some genres have not aged much, such as House, Techno, Breaks, Dub, etc. If they were stocks, you could say they might be blue chips, but making music is not about doing what works for others, but perhaps reflects what one loves at the moment of making it.

It’s easy to be cynical and discouraged, but that is also what happens when you stick to a musical direction. The scene changes and rotates every 5 years, both in the new people joining, genres changing and some other, having families and moving on with their lives.

Perhaps you’re asking me then, how can I not fall out of trends while keeping my identity?

Tricky question here, which will mean I need to share a few thoughts for you to consider.

The quality and relevance of your music is linked to your circle of peers

Whether we like it or not, music doesn’t evolve in isolation. The quality, direction, and even relevance of what you make is strongly influenced by the people you surround yourself with. Not because they dictate your sound, but because they shape what feels normal, interesting, and worth exploring.

Your circle acts as a filter. It filters what you are exposed to, what gets validated, what gets challenged, and what ideas feel “alive” rather than dated. If everyone around you is referencing the duplicate records from ten years ago, chances are your output will orbit that same gravity. That doesn’t mean the music is bad, but it may slowly lose friction with the present moment.

On the other hand, being around people who are curious, slightly ahead of you, or simply different in their approach tends to stretch your ear. You start noticing details you would have ignored before. You hear new solutions to old problems. You’re indirectly trained to refine your taste.

This is often why artists who remain relevant over long periods are deeply embedded in evolving communities. Not necessarily big scenes, but living ones.

Here are a few points to consider if you want a healthier, more stimulating circle.

1. Proximity beats popularity

It’s tempting to anchor yourself to big names, music production trends, or distant scenes, but growth usually happens through proximity. Regular exchanges with people you can actually talk to, share unfinished work with, and receive honest feedback from will have a much more substantial impact than passively consuming what successful artists release.

A small group of engaged peers who make music now, struggle now, and question their process now will do more for your music than following dozens of artists you’ll never interact with. Relevance comes from dialogue, not observation.

Ask yourself: who do I regularly exchange ideas with, not just admire from afar?

TIP: If you feel isolated making music, you can always find communities online. One of the place they go the most nowadays is on Discord. You can join my server here.

2. Diversity matters more than agreement

A circle where everyone shares the same taste, tools, and references can feel comfortable, but it can also quietly trap you. Agreement is reassuring, but friction is educational.

Being around producers who work in different tempos, formats, genres, or even artistic disciplines forces you to articulate why you like what you like. It sharpens your identity rather than diluting it. When someone challenges your assumptions, you’re pushed to either refine them or let them go.

Healthy circles aren’t echo chambers. They’re places where respectful disagreement is valued, and curiosity is more important than being right.

TIP: Try to attend music events where you know absolutely no one. Going to classical music events are quite impressive.

3. Contribution is as essential as consumption

The strength of your circle isn’t just about what you get from it, but what you bring into it. Sharing works in progress, asking thoughtful questions, offering feedback, or simply being present builds trust and depth.

People tend to invest more in those who are engaged rather than those who only show up when they need validation. Over time, this creates a feedback loop in which the quality of exchanges increases, and so does the quality of the work that results.

If your circle feels stagnant, it’s often worth asking not only who am I listening to? but also how am I participating?

Bonus: A mentor can make a difference — but curiosity does the heavy lifting

Having a mentor, coach, or more experienced guide can accelerate growth dramatically. They can help you see blind spots, contextualize your work, and avoid years of trial and error. But mentorship is not a one-way transfer of knowledge.

The quality of what you learn is directly tied to the quality of the questions you ask. Passive consumption leads to shallow results. Active curiosity, experimentation, and reflection turn guidance into transformation.

Two people can receive the same advice and walk away with entirely different outcomes. The difference is rarely talent — it’s attention, curiosity, and the willingness to question one’s own habits.

In that sense, even the best mentor won’t save you from irrelevance if you stop being curious. But intense curiosity, combined with the right people around you, tends to keep your music moving forward — regardless of music production trends.

TIP: A mentor can be a friend who is a producer who is simply more experienced than you. It’s about having someone who can reflect some helpful feedback.

Thinking your way into music can disconnect you from feeling it

There’s a subtle trap many producers fall into over time: replacing playing with thinking. The more aware you become of music production trends, market expectations, genre codes, and “what works,” the easier it is to start composing from the head instead of the body.

At first, this feels like progress. You understand arrangements better. You recognize clichés faster. You know which sounds belong to which aesthetic. But something else quietly fades: emotional feedback. The moment-to-moment sensation of this feels right or this feels wrong gets replaced by this makes sense.

When music is built primarily through analysis, strategy, or imitation, it often loses its grounding. You may still produce competent tracks, but they feel interchangeable — not just to listeners, but eventually to you. This is where disconnection creeps in.

Making music for trends often creates distance from yourself

Chasing music production trends requires external alignment. You’re constantly adjusting your choices to keep up with a moving target. That adjustment process pulls attention away from internal signals: excitement, discomfort, curiosity, and resistance.

Over time, this can create a split. You might release music that “works” socially while feeling oddly detached from it personally. And when you’re disconnected from what you’re making, it becomes harder to occupy a meaningful position within a community. Not because people reject the music, but because it lacks a clear emotional anchor.

Communities tend to form around sincerity and lived experience. Even highly technical scenes respond to work that feels embodied — music that sounds like someone was actually there while making it.

Playing reconnects you to timing, risk, and intuition

Playing music — whether through improvisation, live recording, or exploratory sessions — brings you back into contact with uncertainty. You don’t fully know what’s coming next. You react instead of calculating. You feel time passing instead of arranging it on a grid.

This doesn’t mean abandoning craft or structure. It means letting sensation lead before explanation. Often, the ideas that feel most “you” don’t arrive fully formed. They appear as gestures, accidents, or moods that only make sense afterward.

When producers stay connected to that layer, their work tends to age better. Not because it ignores music production trends, but because it isn’t dependent on them for meaning.

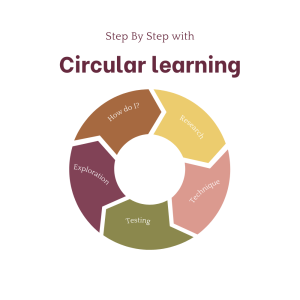

TIP: It is said that learning through being playful consolidates the theory.

Drifting away from your roots isn’t necessarily a failure

Many artists panic when they feel disconnected from where they started. They interpret the drift as a loss of identity or a betrayal of their original sound. But drifting is often part of staying alive creatively.

Exploring unfamiliar aesthetics, tools, or communities can sharpen your sense of self rather than dilute it. You learn what you miss. You discover what no longer resonates. You acquire new skills and perspectives that were impossible within your original framework.

Some artists never return to their roots. Others circle back years later with deeper intent and clarity. Both paths are valid.

What matters is not staying in place, but staying connected to your internal signals as you move. That connection is what allows you to contribute something valuable — whether to an existing scene or to a new one you help create.

Music is a language of patterns — and an invitation to play

At its core, music is a system of patterns. Rhythmic cycles, harmonic movements, timbral signatures, and dynamic arcs — all of these form a vocabulary. When you create music, you’re not just expressing something personal; you’re also building a small language that the listener has to learn on the fly.

This is where listening becomes active. The ear begins anticipating what might come next, recognizing motifs and noticing deviations. Pleasure often comes from that balance between expectation and surprise. Too predictable, and the mind disengages. Too abstract, and the listener loses the thread.

In that sense, every track is a puzzle. Not a problem to solve, but a space to explore.

You’re designing a game, not just a track

Thinking of music as a game can be surprisingly helpful. You define the rules implicitly: how repetition works, how tension resolves, how dense or sparse the information is. The listener’s role is to navigate those rules, learn them, and feel rewarded when they “get” what’s happening.

This doesn’t require complexity. Some of the most effective music relies on very simple ideas, but executed with precision and intention. The game becomes about subtle shifts, micro-variations, or timing rather than overt changes.

When artists are clear about the game they’re proposing, their music tends to feel coherent even when it’s unconventional. When they aren’t, the listener often senses confusion — not because the music is difficult, but because the rules keep changing without reason.

DJs live inside this puzzle

This idea becomes even clearer when you look at how DJs collect and play music. DJs rarely select tracks only because they “like” them in isolation. They’re also listening for function: where does this sit in a set, what energy does it carry, what problem does it solve?

A DJ’s library is essentially a massive modular puzzle. Each track is a piece that can connect to others through tempo, texture, mood, rhythm, or harmonic implication. Good DJs don’t just play tracks — they decode them, understand their internal logic, and then recontextualize them.

That’s also why DJs often hear things producers miss. They listen with the future in mind: how this pattern will interact with another, how a breakdown will feel after twenty minutes of tension, how much information a dancefloor can handle at a given moment.

Writing with awareness doesn’t mean writing to please

Understanding music as a language or puzzle doesn’t mean you should write to satisfy everyone. It means being aware that communication is happening whether you intend it or not.

When you’re clear about your patterns, your rules, and your intentions, you make it easier for listeners — and DJs — to engage deeply with your work. They may not articulate it consciously, but they feel it.

In that sense, relevance doesn’t come from chasing music production trends, but from designing games people want to keep playing.

Luck, pattern recognition, and finding your place

Not all luck is random. One form of luck comes from learning how to read patterns in life — understanding timing, context, and where your energy fits within a larger system. This is something good business owners do instinctively. They observe behaviour, notice cycles, adapt their offer, and reposition themselves without losing their core intent.

Successful musicians operate in a similar way. They don’t just make music in a vacuum; they decode cultural signals. They sense what listeners are hungry for, what feels saturated, and where space is opening. This doesn’t mean they chase music production trends blindly, but that they remain attentive to the environment their music lives in.

When that attention fades, falling out of trend often follows. Not necessarily because the music is “bad,” but because it no longer resonates with the current emotional or social landscape of its community.

Listening is how you recalibrate

When your relationship with listening weakens, your sense of direction usually follows. Listening isn’t just about pleasure or reference gathering — it’s how you stay aligned with the world outside your studio.

There are moments when the music you once loved starts to feel redundant or uninspiring. That can be unsettling, especially if those sounds shaped your identity for years. For me, 2025 felt like that. Tracks that once felt essential began sounding overly familiar. Some artists I respected moved toward directions I couldn’t fully connect with anymore.

Rather than forcing enthusiasm, I took that as information. A signal that my internal patterns had shifted.

Leaving a trend can be an act of alignment.

That’s when techno re-entered my life. Not as a comeback story, but as a re-anchoring. Techno never disappeared, but my attention had drifted toward minimal house in recent years. What excites me now about techno is the freedom it offers: fewer stylistic rules, more room for abstraction, experimentation, and conceptual thinking.

Stepping out of trend, in that sense, isn’t about rejection. It’s about removing constraints that no longer serve you. Redefining your workflow, questioning self-imposed rules, and allowing new avenues to appear often restores momentum more effectively than doubling down on familiarity.

Ironically, this kind of reset often brings you closer to a community rather than further away.

Sunwave Festival (Trommel)

Communities reveal themselves through connection

Once you start moving toward what genuinely excites you, signals appear. DJs are especially valuable here. When a DJ plays your track, or consistently selects music you love, they act as connectors. Their selections show you what else belongs in that ecosystem — what ideas, tempos, moods, and values orbit the same center.

Following those connections helps you locate yourself within a living network rather than a fixed genre. You begin to understand not just what you’re making, but where it belongs and who it speaks to.

In that sense, luck becomes less about being discovered and more about being positioned. And positioning comes from attention, listening, and the courage to move when patterns change.

When a favourite artist grows into something you resist

Almost everyone who follows music long enough experiences this moment: an artist you once loved starts releasing music you actively avoid. The reaction is often emotional — disappointment, confusion, even rejection. It can feel personal, as if something meaningful was taken away.

But if we apply the ideas explored above, this shift becomes less of a failure and more of a signal. Not necessarily that the artist “lost it,” but that their position in the ecosystem changed.

A few lenses can help unpack what might be happening:

-

Their circle may have shifted

As artists grow, their environment often changes. New collaborators, managers, labels, and peer groups come with different values and incentives. These circles influence taste, validation, and what feels worth pursuing. What once felt essential to them may no longer be reinforced in their daily exchanges. -

They may be thinking more than feeling

As expectations rise, spontaneity often gives way to calculation. Deadlines, branding, and audience metrics can slowly replace play and risk. The music may still be polished, but less embodied — more designed than lived. -

Business can reshape intention

Some artists lean deeply into sustainability, visibility, or commercial success. There’s nothing inherently wrong with that, but it often requires compromise. Markets reward clarity, familiarity, and reliability more than ambiguity or experimentation. Over time, this can smooth out the edges that once made the work feel alive to you. -

They might be playing a different game now

This is the most interesting question to sit with: what patterns are they responding to that you’re not seeing? Perhaps they’re addressing a different audience, a different context, or a different phase of their life. Understanding that doesn’t require agreement — only curiosity.

Seen this way, aversion becomes informative. It tells you something about your own values, your listening position, and the patterns you’re attuned to.

And it invites a broader question: not why did they change? but what game are they playing now — and which one do I want to play?

Beyond trends, what remains

If there’s one thread running through all of this, it’s that music is not primarily a product of trends — it’s a product of connection. Connection to people, to feeling, to patterns, to communities, and ultimately to life itself.

Genres come and go because they’re cultural agreements, not emotional anchors. Circles of peers shift, aesthetics rotate, workflows evolve. Staying relevant isn’t about clinging to a style, but about staying attentive: to the people around you, to what you feel while making music, to the patterns emerging in your environment, and to when it’s time to move.

What’s striking is that when we zoom far enough out, trends reveal their true fragility. In elderly people experiencing cognitive decline, music often becomes one of the last remaining bridges to memory. Not the right genre. Not the current sound. But the music that is emotionally tied to lived moments — love, loss, youth, identity. A song can bypass language, logic, and even time itself, reconnecting someone to who they were and how they felt.

At that point, relevance has nothing to do with fashion. What matters is resonance.

This perspective can be grounding for artists. It reminds us that the deepest value of music lies in its ability to carry meaning across time, not just across scenes. Music production Trends may help music circulate, but emotional truth is what allows it to endure.

So perhaps the question isn’t whether chasing genres is a lost cause, but whether we’re willing to make music that stays connected — to ourselves, to others, and to the moments that shape a life. Because long after trends dissolve, that connection is what remains.

How your brain functions can influence your tastes. Some people like complex music (jazz, prog rock, avant-garde electronic) because their brains enjoy deciphering intricate patterns. Being exposed to more challenging music can also mean that you’ve come across many expositions to music and need to be challenged more. Your brain can influence how you listen to music.

How your brain functions can influence your tastes. Some people like complex music (jazz, prog rock, avant-garde electronic) because their brains enjoy deciphering intricate patterns. Being exposed to more challenging music can also mean that you’ve come across many expositions to music and need to be challenged more. Your brain can influence how you listen to music.

One thing that I love doing is to work with unestablished artists. It’s why I have

One thing that I love doing is to work with unestablished artists. It’s why I have  Not all genres are the same, and they require different equipment. If you were to record a cowboy outlaw record, it’s probably not the best idea to go to a micro house producer. However, I have had rock bands come to me because they wanted their album to sound electronic in nature, despite it being a rock album.

Not all genres are the same, and they require different equipment. If you were to record a cowboy outlaw record, it’s probably not the best idea to go to a micro house producer. However, I have had rock bands come to me because they wanted their album to sound electronic in nature, despite it being a rock album. Perception is reality, and some people have different perceptions on what things are supposed to be. Especially when dealing with their art. With audio, producers often get married to their sounds, thinking that they should be specifically in this spot in the mix, when, in reality, it probably won’t translate the way you want it to. This may come from hearing said sound over and over again in whatever room, or on whatever medium they were listening to while they were making it. However, in a well treated room, with calibrated equipment, or conversely, in a club with a good, or poor sound system, it may not translate exactly how you anticipate. Some people are more judicious about this, and accept the reality. However, some you just can’t please. So is the way of the artist.

Perception is reality, and some people have different perceptions on what things are supposed to be. Especially when dealing with their art. With audio, producers often get married to their sounds, thinking that they should be specifically in this spot in the mix, when, in reality, it probably won’t translate the way you want it to. This may come from hearing said sound over and over again in whatever room, or on whatever medium they were listening to while they were making it. However, in a well treated room, with calibrated equipment, or conversely, in a club with a good, or poor sound system, it may not translate exactly how you anticipate. Some people are more judicious about this, and accept the reality. However, some you just can’t please. So is the way of the artist. Engineers get that artists have a lot of things to say about their work, and may use poetic language in order to communicate it. And this prose sometimes leads to elaboration. However, there is a saying in sales, called K.I.S.S, which stands for Keep It Simple, Stupid. This is because people understand things if they are simplified. No need to get technical, or elaborate. Just say what you mean. A good way of easily communicating is to provide examples of things that already exist. Let’s be real, nothing is new under the sun, so if we can pinpoint where that idea is coming from, then maybe it can be recreated, with a flourish that makes it your own.

Engineers get that artists have a lot of things to say about their work, and may use poetic language in order to communicate it. And this prose sometimes leads to elaboration. However, there is a saying in sales, called K.I.S.S, which stands for Keep It Simple, Stupid. This is because people understand things if they are simplified. No need to get technical, or elaborate. Just say what you mean. A good way of easily communicating is to provide examples of things that already exist. Let’s be real, nothing is new under the sun, so if we can pinpoint where that idea is coming from, then maybe it can be recreated, with a flourish that makes it your own.