Is It Best To Produce One Style, Or Many?

Why do people keep producing the same kind of track when there are others who have a wide palate of styles? I’ll admit, I’m a victim of the former. I’ve been producing the same type of music forever. Sure, often they sound different, but overall, I use the same formula and workflow, which translates into a bunch of songs that sound somewhat identical. This results in some people questioning why I don’t expand my palate.

In response, I try to break out of the mold and create something entirely different. Then, the people who listen to me because of my consistency get annoyed and start complaining. There is no victory here, which is why I always suggest just making music for yourself. At the end of the day, the best thing you can do is be satisfied with your finished product. However, let’s explore the advantages of disadvantages between the two.

Producing A Similar Sound

Ok, let’s first talk about making the same song over and over again. In an era of algorithms and playlists, this is a sensible approach if you want to build a brand. With streaming, listeners have infinite choices nowadays. They can go on Spotify or YouTube and build their own playlists that fit their mood. And when they want to augment their mood, they often go and grab songs from familiar artists that satisfy that emotion. If you’re an artist that produces a bunch of different styles, they may not go check out your new stuff, because they know that it won’t fufill that emotional anchor. However, if you have a palate of sounds, tempos and styles that fit into a similar trope, then listeners can reliably count on you to produce something that satisfies their need.

The Benefit Incremental Improvements On A Sound

Another reason for producing similar-sounding tracks is because the artist wants to keep on improving on something. Often they believe if they keep on working in the same vein that their tracks will get progressively better, which may lead to some sort of breakout moment. If they decide to take a tangent into other realms, then that may cause them to lose sight of that goal. They may even start making more predictable, cookie-cutter stuff since often when artists explore new genres, they start watching tutorials that thousands of other producers have watched. Often, this regresses their sound, when by staying the course it may have led to new, exciting sounds, even if they fall inside a stereotypical frame that they defined throughout their years of producing.

What To Do With All Of These Similar Tracks?

When you have 100 songs and they’re all the same, what do you do? Is that a waste? If you release all these 100 songs, you’ll burn yourself out because not all are worthy of release. I usually recommend making bundles of 3 or 4 and seeing which ones work by passing them to DJ friends who can play them. They’ll let you know which ones work, and what doesn’t.

Also, don’t forget to store all of your projects. You never know when you can go back and finish a track with the new skills you have acquired.

How To Change Your Sound, Without Becoming Cookie Cutter

However, there are ways for producers to keep a template and still change their sound. For instance, they can change the key. Each key has a different mood associated with it, and while the timbres and samples may be the same, the new pitch can redefine the emotional impact. You can still retain the mood that listeners expect if you switch the key to something harmonically relevant to a previous song’s key. Just check the Circle of Fifths to find out what works harmonically.

Another thing composers can do is time signature changes or add polyrhyms in their music. In dance music, it’s often hard to do something outside of 4/4. Sure, there are some tracks that work, like Jon Hopkin’s “Neon Drum Pattern,” which is in 5/4, or the rave classic, Jakatta’s “American Dream.” However, those are a pain to mix, and are a rare breed of dance songs. What I suggest is things like using triplets, or doing things like making your song half time or cut time. Another thing you can do is make your rhythm 4/4, and your lead 6/4, since they are both common time. However, if you don’t care if your songs are mixable, feel free to make songs in 9/8 or 17/4. Who cares? Like I said, it’s about feeling satisfied with your music, and nothing else.

Producing Many Different Styles

Ok, so let’s talk about artists who have a bunch of different styles. I would also say that I do this too, as I release dub techno, minimal, ambient, and more. However, with my sound, it all comes from a similar root, as I mentioned before.

Then there are artists that are all over the place, and cannot stay tied town to one process. A good example of this is the band Underworld. You might now them for their song Born Slippy, but they are way way more than that. They were originally an ‘80s rock band that evolved into the techno juggernaut that we know today. However, if you go through their catalog, you will hear many genres of music. There is house, techno, and breaks, for sure. But there are also ballads, and ambient pieces. Sometimes there are big beat songs as well. Then occassionally, they’ll return back to their roots and make a more rock oriented song.

Another good example is Radiohead. Pretty much every album they change up their style. Ok Computer does not sound like Kid A, Kid A does not sound like In Rainbows, In Rainbows does not sound like King of Limbs, A Moonshaped Pool does not sound like King of Limbs. This process all started with Kid A when they wanted to make an anti-album that was intended to alienate their fans by switching things up dramatically, replacing drums with drum machines, guitars with synths, and normal vocals, with distorted ones. In other words, they were sick of stardom. But that backfired, and it became arguably the most critically acclaimed album of that decade.

Having An Artistic Signature To Tie It Together

However, if there is one thing that Underworld and Radiohead have in common is that they have an artistic signature, whether they like it or not. With Underworld it’s the timbre of the sounds they chose, paired with Karl Hyde’s spoken word vocals. With Radiohead, it’s the production veneer and Thom Yorke’s distinct crooning. This keeps the fan grounded in familiarity, even when the styles change.

We Live In A Different Era

Keep in mind that Underworld and Radiohead are from a different time though. They existed in a time when I believe labels were looking for artists that pushed the limits of their creativity. Nowadays, with algorithmic streaming, labels are often looking for consistency, because they have artists put into boxes that they can market to said demographic. If you’re going to take this route, you may have to self release, or do a lot of research in finding a label that still has this old ethos.

Frank Zappa has this great interview where he laments that cool kids running labels ruined artistic expression. He says that in the ‘60s, the reason why so much amazing, forward-thinking music broke into the mainstream is because the label heads were just old businessmen who didn’t know anything about music. They were like, “what do I know? Put it out, see what happens.” Then some of those records had great success, so they hired young, long-haired hippies to come in to advise. Those hippies became smug and decided they knew what was best, because they had taste, and thus began the decline of forward-thinking music, because often, they had no idea, despite thinking that they did.

This has progressively became worse, and now these label executives have developed formulas for what should be released and what shouldn’t. Luckily, we live in an era where self distirbution is possible, and with the right marketing, and luck, you really never know where your multigenre music can go.

Whatever Route You Chose, It Doesn’t Matter

Whichever route you choose, there is no right and wrong. Releasing the same sort of song can be fulfilling from a commercial standpoint, but from an artistic standpoint, it can become dull. Chances are most musicians are not going to be touring with thousands of adoring fans, so it might behooth you to make whatever you want, rather than trying to placate a potential audience. But, if you have a sound and know how to market it, then by all means, refine it. God knows that’s what I did. But I also expanded into other genres too. So perhaps, somewhere in the middle is a solid approach

For example, many people feel that they want to become a DJ after a special night in a club. This is an example of musical stimulation kicking off the cycle of inspiration. People also like to celebrate art, in search of some sort of new stimulation for the mind; to be inspired to create.

For example, many people feel that they want to become a DJ after a special night in a club. This is an example of musical stimulation kicking off the cycle of inspiration. People also like to celebrate art, in search of some sort of new stimulation for the mind; to be inspired to create. This phase can be when the “aha!” moment hits you full effect; all the technical details fall into place and you can express yourself entirely. I’ve had this moment with two albums I made,

This phase can be when the “aha!” moment hits you full effect; all the technical details fall into place and you can express yourself entirely. I’ve had this moment with two albums I made,

Legato: This is probably the most useful thing to activate for clips in variation. Basically, the Legato option will let the selected clip to take over the one that was previously played, based on the quantization you have set. So for instance, let’s say you play a hihat clip, then press the first clip of the variation. It will stop the activated clip and immediately switch to the other one you just started. On the image, I have set it to 1/16, meaning it will be played on the next 1/16th, keeping it on tempo. Keep in mind that the variation clips are “in sync” with the one playing so that it will continue at the same position in the clip. If legato wasn’t activated, it would start at the beginning of the clip.

Legato: This is probably the most useful thing to activate for clips in variation. Basically, the Legato option will let the selected clip to take over the one that was previously played, based on the quantization you have set. So for instance, let’s say you play a hihat clip, then press the first clip of the variation. It will stop the activated clip and immediately switch to the other one you just started. On the image, I have set it to 1/16, meaning it will be played on the next 1/16th, keeping it on tempo. Keep in mind that the variation clips are “in sync” with the one playing so that it will continue at the same position in the clip. If legato wasn’t activated, it would start at the beginning of the clip. Intensity Variation: If you want to quickly go from open hihat to closed one, one of the fastest way is to play with the “Preserve” section and set it as in this image. Playing with the percentage will let you adjust how much of the end of each sound can be preserved. Having it at 100% is fully open and let’s say 25% is more closed, building tension. So one variation can be set low at first and then the other ones can be more open. If you see the need to boost the energy quickly, then you can go in one of the variation.

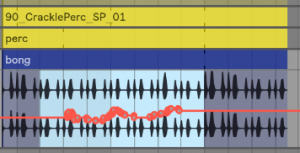

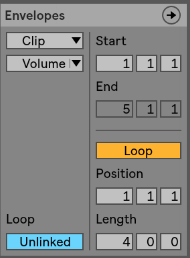

Intensity Variation: If you want to quickly go from open hihat to closed one, one of the fastest way is to play with the “Preserve” section and set it as in this image. Playing with the percentage will let you adjust how much of the end of each sound can be preserved. Having it at 100% is fully open and let’s say 25% is more closed, building tension. So one variation can be set low at first and then the other ones can be more open. If you see the need to boost the energy quickly, then you can go in one of the variation. Envelopes: Super useful for variations as well because you can create automation on a very small scale or a longer one. Many artists will use this on EQ to give life to a clip and making sure it feels like it is alive. The important part is to make sure that the envelope isn’t linked and then you can decide of the length of the automation, on one attribute. Tip: make sure you select “Clip” in the first drop down to make sure the changes are made in the clip itself.

Envelopes: Super useful for variations as well because you can create automation on a very small scale or a longer one. Many artists will use this on EQ to give life to a clip and making sure it feels like it is alive. The important part is to make sure that the envelope isn’t linked and then you can decide of the length of the automation, on one attribute. Tip: make sure you select “Clip” in the first drop down to make sure the changes are made in the clip itself.

One of my friends came to my home one day and showed me a stunning album he made which totally blew me away. We quickly started talking production and he explained me that he was using Cool Edit (a very simple sound editor which in the early 2000s wasn’t even considered a DAW!) and no equipment whatsoever. None. Everything was made from scratch and with a lot of patience. Honestly, he changed my perspective on gear forever. Every time someone tells me they “need this” or “need that” to start working on their music, I have to yell “bullshit!” because I know and have heard otherwise.

One of my friends came to my home one day and showed me a stunning album he made which totally blew me away. We quickly started talking production and he explained me that he was using Cool Edit (a very simple sound editor which in the early 2000s wasn’t even considered a DAW!) and no equipment whatsoever. None. Everything was made from scratch and with a lot of patience. Honestly, he changed my perspective on gear forever. Every time someone tells me they “need this” or “need that” to start working on their music, I have to yell “bullshit!” because I know and have heard otherwise. In a sense, musical intuition is what defines someone who can bring a bit of creative magic into something, in comparison to someone who sticks to truly technical application of software. I’ve often had the chance to watch experienced producers make music, either while I was visiting one’s studio or on the spur of the moment of a jam. For instance, we once had the infamous Narod Niki experience at Montreal’s MUTEK in the early 2000’s where Zip, Villalobos, Dan Bell, Akufen, Cabanne, Dandy Jack, Monolake (even Cassy sang for some minutes) all synced their laptop and gear to improvise a show for us. Our local festival gave us many opportunities to watch, what I would call, masters in what they do, play in front of a crowd to present how to create and perform. The live act itself, when done properly, should sort of represent what the artist is doing in his or her studio, but in a way that can bring the crowd on a journey.

In a sense, musical intuition is what defines someone who can bring a bit of creative magic into something, in comparison to someone who sticks to truly technical application of software. I’ve often had the chance to watch experienced producers make music, either while I was visiting one’s studio or on the spur of the moment of a jam. For instance, we once had the infamous Narod Niki experience at Montreal’s MUTEK in the early 2000’s where Zip, Villalobos, Dan Bell, Akufen, Cabanne, Dandy Jack, Monolake (even Cassy sang for some minutes) all synced their laptop and gear to improvise a show for us. Our local festival gave us many opportunities to watch, what I would call, masters in what they do, play in front of a crowd to present how to create and perform. The live act itself, when done properly, should sort of represent what the artist is doing in his or her studio, but in a way that can bring the crowd on a journey. A notable example would be an artist, during a live show, dropping some sounds or a musical idea that was unexpected but works with what’s happening at the current moment completely. Another example could be a musician proposing a random idea and having that incomprehensible idea make total sense after 2-3 minutes or development.

A notable example would be an artist, during a live show, dropping some sounds or a musical idea that was unexpected but works with what’s happening at the current moment completely. Another example could be a musician proposing a random idea and having that incomprehensible idea make total sense after 2-3 minutes or development. The path doesn’t need to be cleared from obstacles. Obstacles are the path. (Buddhist Proverb)

The path doesn’t need to be cleared from obstacles. Obstacles are the path. (Buddhist Proverb)