Equipment Needed to Make Music – Gear vs. Experience vs. Monitoring

This post follows a previous one I made regarding the minimum equipment needed to make music; due to the popularity of that post and the number of questions I had afterwards, I wanted to dive deeper into my thoughts on this.

I’m often asked what matters the most between equipment, experience, and monitoring, and I give someone the following advice on those three topics:

The Role of Experience

There is absolutely no doubt at all that someone’s experience, more importantly than anything, will have the biggest impact on the quality of the music he or she makes. A producer with years of experience knows what works and what doesn’t. Even without the proper equipment, he or she will find ways to maximize the tools they are limited to in order to get the make the most of their gear, and sometimes can even turn something very insignificant into a piece of art. What’s also something to understand is that experience can also guide you to make strategic decisions based on past experiences. For example, someone who has made high quality products knows that reaching out to others who can help is a valuable, essential part of the process. Also, if you’re faced with limitations, the internet is filled with information about how to make the best of your situation. Lacking sounds you love? Find a sample pack and buy it. Lacking ideas or technique? Look stuff up on YouTube. There’s an abundance of information that is either free or cheap. Investing in little things like personal connections is not only a great way to build support among people who can help you later, but it’s also a way to stay on top of new and better tools that come out from people who and work with develop them.

Studio Monitors Matter

The biggest mistake I see in people who are just starting out, is to invest in cheap studio monitors because of their budget limitations. I know this one is tricky because many people have small budgets. Monitors are something you want to have for the next 10 years minimum, and you want them to be the best pair you can afford. Though experience is the most important thing to consider, but you can’t start with it if you have none, monitoring is to me, what’s you need to focus on as a close second. Studio monitors are your “eyes” in music making: if you can’t “see” what you do, your music will not be precise and the end result might be difficult to appreciate after it leaves your studio. Having proper speakers is like having access to glasses when you can’t see: all of a sudden, everything is clear and you’ll know exactly what’s not working.

- Tight budget? I find that if you can’t invest in good monitors, it’s worth waiting. There are many ways to raise money, from getting a loan or asking relatives, or whatever. But investing in cheap speakers will only benefit you in the short run and will be a major problem in the long term. In the meantime, try getting good headphones that feel good for you when listening to your favorite songs. Go in a store and spend some time comparing models. Comfort is also important.

- What if music production isn’t for you? If you want to produce, it’s probably because you’re a music lover. If you give up on production after buying monitors (note: contact me before doing that!), you’ll still have great speakers to DJ on or to just to listen to.

- Having a subwoofer is a game changer. To me this is an indisputable fact; you’ll see what I mean if you get one or if you get to hear a setup that makes use of one. Thin walls? Angry neighbors will love you if you get a Subpac instead.

The takeaway here: music equipment is a useful but luxurious tool.

One of my friends came to my home one day and showed me a stunning album he made which totally blew me away. We quickly started talking production and he explained me that he was using Cool Edit (a very simple sound editor which in the early 2000s wasn’t even considered a DAW!) and no equipment whatsoever. None. Everything was made from scratch and with a lot of patience. Honestly, he changed my perspective on gear forever. Every time someone tells me they “need this” or “need that” to start working on their music, I have to yell “bullshit!” because I know and have heard otherwise.

One of my friends came to my home one day and showed me a stunning album he made which totally blew me away. We quickly started talking production and he explained me that he was using Cool Edit (a very simple sound editor which in the early 2000s wasn’t even considered a DAW!) and no equipment whatsoever. None. Everything was made from scratch and with a lot of patience. Honestly, he changed my perspective on gear forever. Every time someone tells me they “need this” or “need that” to start working on their music, I have to yell “bullshit!” because I know and have heard otherwise.

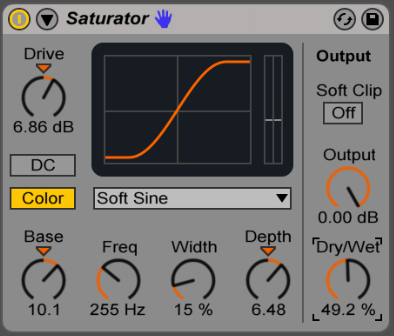

The Role of Additional Gear

“Yeah but I love the feeling of touching knobs to produce!”

So, where should you start if you want to explore the tactile dimension of producing? If you still feel the need to buy equipment beyond a good pair of monitors, I would recommend the following:

- Explore to know what you love doing and invest based on what you decide you like. Don’t fall for the classic “If I just have the [insert trendy piece of gear name here], then I will be okay.” Try to understand music on your computer first: play with synths, make beats, see what you like, and after a few songs, maybe you’ll notice you love synths that sound like a Moog. Learn to understand what kind of sounds you like, just like how you find out what labels an artist releases with. The more you know, the more you’ll be able to invest properly.

- Buy used, rent if possible. Or go hang out with someone who has gear you can try. Make a song with their gear to see if it feels good for you.

- MIDI controllers are always a good investment no matter what but aren’t essential.

Truthfully, there is no such thing as minimum equipment needed to make music, but the things I’ve outline here are things that will help you get started. I hope this helps!

SEE ALSO : What is the Electronic Music Equipment Needed to Start Producing?

The truth is, wherever you want to go in music, you first need to produce a ton of tracks and find your path in that process. Bonus (

The truth is, wherever you want to go in music, you first need to produce a ton of tracks and find your path in that process. Bonus ( In a very digital age many people have become less social, which can make going out and meeting new people harder. I get that. Yet, not being part of a strong network doesn’t mean you won’t create great music, it simply means without having that support you may not be pushed to create your best music.

In a very digital age many people have become less social, which can make going out and meeting new people harder. I get that. Yet, not being part of a strong network doesn’t mean you won’t create great music, it simply means without having that support you may not be pushed to create your best music. What is a mature sounding track?

What is a mature sounding track?

Two of the biggest examples in electronic music are Richie Hawtin’s Plastikman moniker and Aphex Twin, each with their own identifiable sound and even logo. Some artists, like Daft Punk, will take the concept even further, donning elaborate costumes during live performances to avoid ever showing their faces.

Two of the biggest examples in electronic music are Richie Hawtin’s Plastikman moniker and Aphex Twin, each with their own identifiable sound and even logo. Some artists, like Daft Punk, will take the concept even further, donning elaborate costumes during live performances to avoid ever showing their faces.