Arpeggios Technical Dive

In the vast world of music, arpeggios have served as an integral element in composition, bridging the gap between harmony and melody. By understanding its roots, one can appreciate its profound effect on modern electronic music.

Origins of Arpeggios

An arpeggio, derived from the Italian word “arpeggiare,” which means “to play on a harp,” refers to the playing of individual notes of a chord consecutively rather than simultaneously. Historically, arpeggios have roots in classical music. Classical guitarists, pianists, and harpists frequently employ them to express chord progressions melodically.

Functionally, an arpeggio can convey the essence of a chord while providing movement. It serves as a bridge between harmony, where notes are sounded simultaneously, and melody, where notes are played sequentially. This bridging effect imparts a richer texture to compositions, allowing for a smoother transition between harmonic and melodic sections.

Arpeggios in Electronic Music

With the evolution of electronic music, arpeggios found a new platform for exploration. When synths started to be commercialized, they more than often included an internal arpeggiator. Even smaller options like Casios had some simple one. Synthesizers, with their ability to shape and modulate sound, provided the perfect tool to push the boundaries of traditional arpeggios.

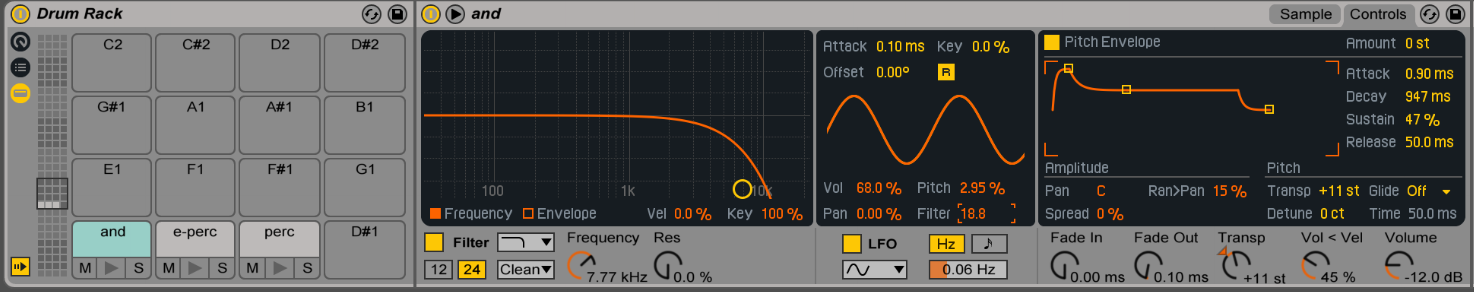

- Synthesizers and Arpeggiation: Many synthesizers, both hardware and software-based, come with built-in arpeggiators. These tools automatically create arpeggios based on the notes played and parameters set by the user. Parameters like direction (up, down, up-down), range (number of octaves covered), and pattern (the rhythmic sequence of the arpeggio) can be adjusted to achieve specific tonal effects.

- Arpeggio Plug-ins: Beyond built-in synthesizer capabilities, there are standalone software plug-ins dedicated to advanced arpeggiation. These tools offer extended control over how the arpeggio behaves and can be integrated into digital audio workstations (DAWs). They often come with pattern libraries, giving producers a starting point which can be tweaked further.

- Sequencing Arpeggios: Sequencers, commonly found in drum machines and DAWs, allow for the programming of notes in a specific sequence. This technique offers a manual approach to arpeggiation, allowing for unique and intricate patterns beyond the capabilities of traditional arpeggiators.

For many people, when musicians would first test a synth, they would at one point test the arpeggiator. In the 70’s until the 90’s, electronic music had more than often, some arpeggiation used. It could be for the bass or for the main hook.

The Impact on Electronic Music

Arpeggios in electronic music often lend rhythmic drive and melodic structure, especially in genres like trance, techno, and synthwave. The repetitive nature of these genres marries well with the cyclical patterns of arpeggios.

Additionally, with the sound-shaping capabilities of synthesizers, the tonal quality of arpeggios can be manipulated. By modulating aspects like filter cutoffs, resonance, and envelope parameters in real-time, arpeggios can evolve and transform throughout a track, adding dynamic interest.

A fascinating aspect of electronic music lies in the observation that many of its melodies are constructed from sequences which can be effectively replicated using an arpeggiator. This isn’t mere coincidence. Electronic music, with its repetitive structures and emphasis on timbral evolution, often favors linear, cyclical melodic patterns. An arpeggiator excels in this realm, offering a systematic approach to crafting these melodies.

Consider classic electronic tracks: many feature melodies that iterate over a set pattern of notes, evolving more through sound manipulation (like filter sweeps or resonance changes) than through note variation. This approach provides a consistent foundation upon which the rest of the track can evolve, allowing other elements, like rhythm and harmony, to play more dynamic roles.

Parallel and Modulated Patterns

1. Parallel Arpeggios:

- Method: Start by setting two arpeggiators with the same note input but adjust one to operate in a higher octave range than the other. You’ll achieve a harmonized melodic pattern where both arpeggios play in tandem, producing a richer sound.

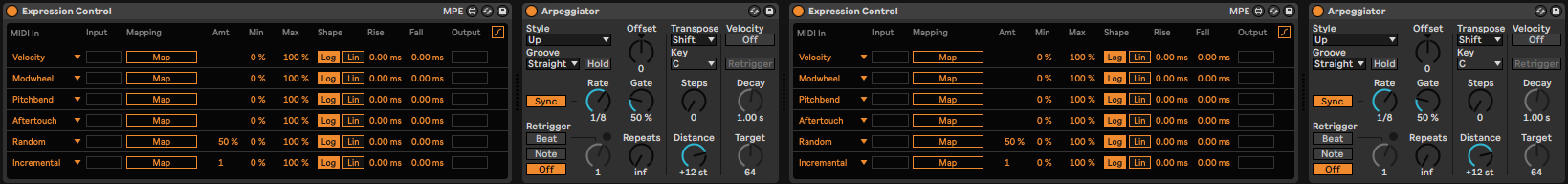

- Experiment: Tweak the rhythm or gate length of one arpeggiator slightly. This introduces a phasing effect, where the two arpeggios drift in and out of sync, creating rhythmic tension and release. Another fun experiment to try would be to create a macro from an arpeggio and then you have a a tool that is also parallel. Make sure your receiving instrument is polyphonic because there will be many notes. I’d recommend trying the arpeggios on different speeds with a pitch/octave modifier so they play notes from different octaves.

2. Side-by-Side Arpeggios Modulating Each Other:

- Method: Use one arpeggiator’s output to modulate parameters of a second arpeggiator or its associated synthesizer. For example, you can set the velocity output of Arpeggiator A to control the filter cutoff or resonance of Arpeggiator B’s synth.

- Experiment: Introduce a slow LFO (Low-Frequency Oscillator) to modulate a parameter on Arpeggiator A (like its rate/speed). This will cause the modulations impacting Arpeggiator B to change over time, introducing evolving dynamics to the piece. I like to have the first Arp to be slow and random and the second one, faster, higher notes.

Power user super combo

TIP: Arpeggiators become super powerful if you use an Expression Control tool so that you can modulate the gate, steps, rate and distance. This will spit out hook ideas within a few minutes of jamming.

Plugins

There are multiple plugins that can be good alternatives to your DAW’s regular arpeggio. It’s always good to have 3rd party plugins so you can step out of the DAW’s generic sound.

This is definitely inspired by the various modular options existing. They’re all regrouped under one plugin that does a bit what many different free tools do like Snake, but of course, the played root note will influence the sequence, which something like Snake doesn’t. Stepic is often used online in Ambient making tutorials. It is great for creating generative melodies and psychedelic melodies.

Everything the guys of Xfer do, is always solid and well thought out. This one doesn’t disappoint. With so many presets existing out there, you can also randomize and quickly tweak your own sequence.

AlexKid has done multiple tools for Ableton Live and each of them found their way into so many people’s workflow, either to start an idea or to have a quick placeholder. This one is similar to Stepic in a way, but just a different workflow. The UI is cleaner and easier to read than Stepic, making it a quick tool for adding decorative melodies or simple basslines. The randomizer has nice options for controlling its results.

Conclusion

From their origins in classical expressions to their modern applications in electronic music, arpeggios have remained a compelling tool for musicians. Through synthesizers and plugins, electronic music producers have a vast palette at their fingertips to experiment and innovate. As technology advances, it’s certain that the use and evolution of arpeggios in electronic landscapes will continue to captivate and inspire.

The first thing producers can do is listen to music before they make it. This might be a huge “duh” statement, but how many people actively listen to music? How many people come home, crack a beer, put on a record, and then just sit there, doing nothing else, except engaging with the music? 10%, maybe? However, it’s this 10% of people who have set themselves up for success if they are music writers themselves.

The first thing producers can do is listen to music before they make it. This might be a huge “duh” statement, but how many people actively listen to music? How many people come home, crack a beer, put on a record, and then just sit there, doing nothing else, except engaging with the music? 10%, maybe? However, it’s this 10% of people who have set themselves up for success if they are music writers themselves.

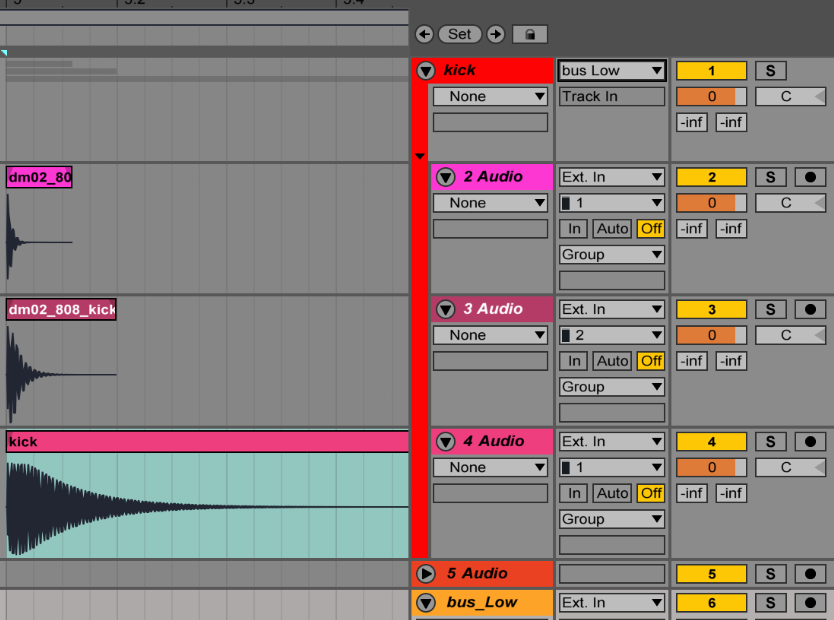

Visually it looks better and is easier to manage, and additionally you can also put effects on the group to glue all the sounds together – generally you’ll need a compressor and one or two EQs for a relatively uniform group. Once I’ve done that, I usually like to have an additional bus for all sounds (eg. groups) that will glue everything else together.

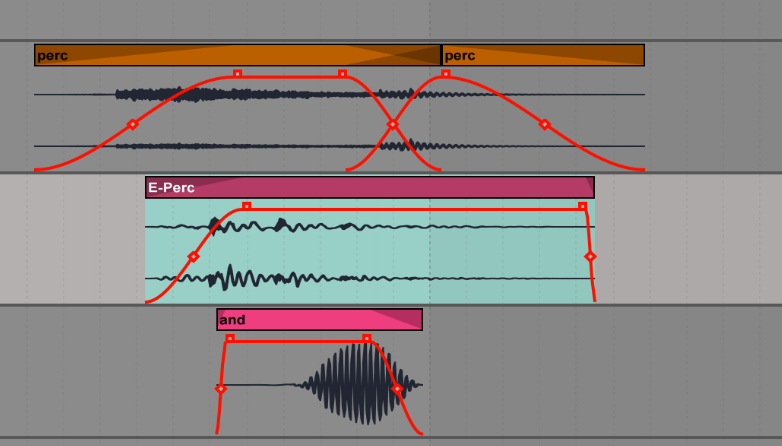

Visually it looks better and is easier to manage, and additionally you can also put effects on the group to glue all the sounds together – generally you’ll need a compressor and one or two EQs for a relatively uniform group. Once I’ve done that, I usually like to have an additional bus for all sounds (eg. groups) that will glue everything else together. If you work in the arranger, you drop sounds in the channel and it’s an easy way to see the layers. I like turning off the grid to do this so it feels a bit more natural.

If you work in the arranger, you drop sounds in the channel and it’s an easy way to see the layers. I like turning off the grid to do this so it feels a bit more natural.