Building a great groove

Have you ever been on a dance-floor and heard a track that connects with you in a very physical way? Physical connection creates a sort of energy that is infectious and makes you want to dance until your feet give up. This feeling is all about the groove in a track; creating a groove makes the combination of elements and arrangement feel just right to keep you dancing. What follows in this post is my personal take on groove, and the steps I’ve learned that I think work best to create a great groove.

Taking into account that everyone has a particular taste, a groove that can give me this irrevocable urge to dance may not do the same for you, and on the other hand, you may relate to other tracks in the same way which don’t do anything for me. To better understand groove, I recommend that you take a step back and subject yourself to some critical listening.

Critical listening includes listening to some reference tracks with your eyes closed and making mental notes of what seems to work best. How do the elements in the track relate to one another? What kinds of sounds are used? Is the groove driving or swing-y? Listening this way will give you great ideas with regards to what works and what feels forced for you personally. I cannot stress this point enough. Have you ever made a track which you felt was “good” but didn’t create a sense of physical movement or urge to dance? Review the groove and change it, and you’ll hear an improvement.

Based on my own personal taste, I feel that when it comes to groove, less is more in terms of what works best. Subtlety coupled with taking extra care in the sound design/sample-selection stage will help your ideas flow smoothly. Understand which sounds you want to be the “protagonists” from the get-go, and you will be able to fill the space much more naturally.

Workflow for creating a groove

- Build a simple pattern. After designing some sounds you feel are nice, take them and start constructing the foundation of your groove. While most of the time drums and percussion are associated with the groove, they are not the only parts which have to work in order to have a nice flow. Pheek’s Guide to Percussion has some great tips on call and response—a concept you must focus on quite a bit to build a solid groove.

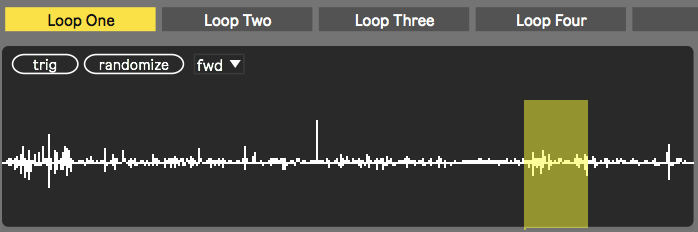

- Once you have your pattern, add some variations to it. A variation could be muting the kick every eighth bar, or having a hat come in and out sporadically, or even changing the note of a synth stab you are using for the groove. You’ll notice that your groove already feels more complete once you add some variations. Micro-variations help to keep the listener interested as the pattern evolves a bit within itself.

- Swing is your best friend! It doesn’t matter if you’re working inside the box or with hardware—take your pattern and apply some swing to it, whether it be via Ableton groove pool or just micro-timing changes (moving things just a tad off grid), this will make this pattern feel less robotic which is what we are going for. This last point is very important for a nice groove, but some kinds of music don’t apply this technique as aggressively because they are just hard hitting and energy driven, but many others rely on these small details and time changes to give a human touch to the pattern.

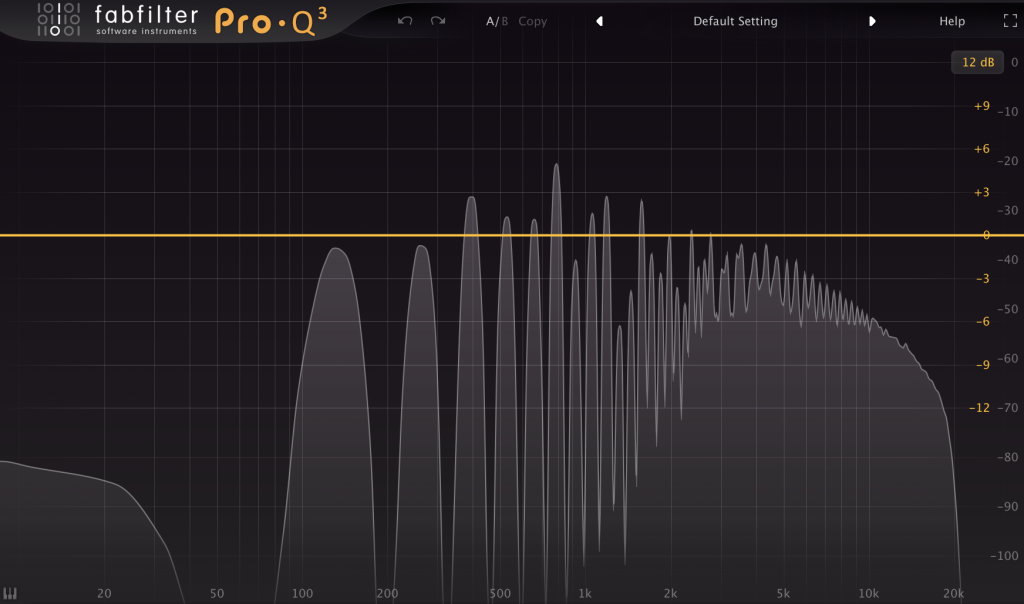

- Add some effects to your sounds. Instead of programming each MIDI note or step, add some delays—both triplets and eighth notes work well—with some very short feedback and dry/wet. Here’s where you can go crazy experimenting—you will notice that when you use these delays and reverbs your sound begins to morph and ghost notes appear in the background, which make things feel fuller and glued together.

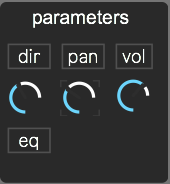

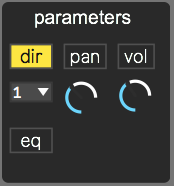

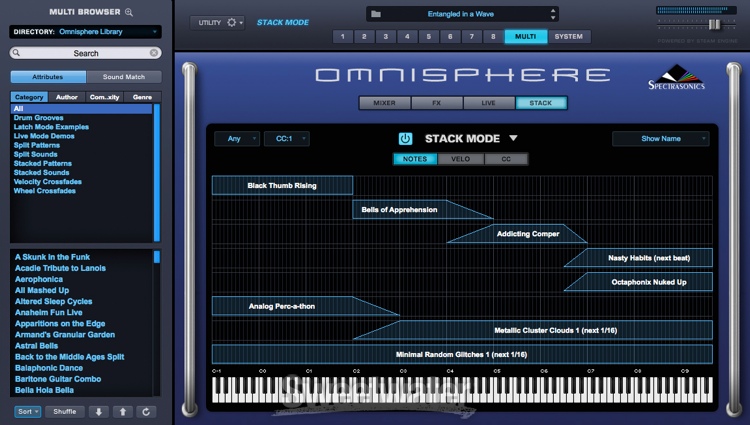

- To continue morphing it, apply some modulations and LFOs to control different aspects of a sound; from panning to volume, modulation allows a pattern to evolve on a macro-scale and creates movement, which is crucial in creating a great groove.

Don’t forget that it’s important that all your elements work well together. If you feel something is out of place, take a couple of minutes to review it—experiment and you’ll create “happy mistakes” which end up being great. I like to use the word coherence to describe how things work together in a track. If a track has a coherent groove in which the drums, bass-line, synths, and other parts work well together, then it will be infectious. Many people use the coherence approach, and you can go crazy with it. Again, listen to some references and use them as a starting point while asking yourself the important questions:

How much swing does the pattern have?

How does the bass-line relate to the percussion and main drums?

Are synths being used rhythmically or as background sounds?

Don’t be afraid to revise a groove, but also learn when to compromise—after a session take a break and come back to it with fresh ears. If your groove is solid, you will feel it. If not, you’ll have an easier time fixing it when your perspective is fresh.

SEE ALSO : Honing your production skills before releasing music