Creating tension in music

Electronic music—oriented for dance-floors—mainly relies on the use of tension to create excitement. I was recently asked how I personally approach tension-building in my work. In this post I’d like to share my point of view on the subject, but before writing this I also spent some time reading articles about tension in music to see how it’s approached by others. To my surprise, I didn’t find anything I could really relate to. Many approaches to creating tension use common, established techniques, and it seems like most of the advice about this topic was for rock-type music. While the techniques I read about are interesting, I firmly believe that you need to understand the reasons behind creating tension in music first, and once you understand them, you might find that things I discuss in this post are still relevant 10 years from now. Personally, I’ve been approaching tension-building in my music the same way for the last 20 years, from a philosophical point of view.

There’s a moment that stands out to me most with regards to my first true understanding of tension in electronic music. I spent the first few years of my DJ career as the opening act. I’d be the minimal dude that plays mellow, heady, trippy stuff, which—at the time in Montreal’s scene—meant opening slots. No complaints here though; this part of my career is when I learned the most about playing live. Opening a show is one of the most misunderstood roles in live music; it’s far more important than most people think.

When people start arriving at a show, the club is empty and there’s already a bit of awkwardness and natural tension mixed in with the audience’s excitement and anticipation. People arrive with expectations, and the opening artist is usually there to set the mood and to build a foundation for what the night will become (which includes not playing too uptempo if the floor is empty). Creating sonic comfort as the opening act is essential.

It’s difficult to create tension if you haven’t yet created a trusting relationship with the people at the event while performing. You’ve probably read many times that the best DJs are the ones that know how to read a crowd—and there’s a reason for this; you have to be aware of the audience’s needs and how to fulfill them, but also of how to create anticipation before addressing those needs: this is tension-building.

Now, it’s important to understand that there are three main tension-building scenarios in music:

- Circumstantial. In a given context, some natural tension/excitement might already exist, such as playing your last song before the headliner plays. Those 5 minutes will be naturally more tense as people’s eyes and ears are getting ready for the main act, and the music is supporting this anticipation.

- DJ-related. When a DJ knows how to play a track at the right moment and combine it with something else to create an experience, then the music becomes part of a puzzle.

- Music-made. This type of tension is created within a song itself, sonically via producing.

When you understand that your music might be heard in these three different contexts, it can give you a better idea of what sort of tension might be best for you personally to create. For instance, perhaps you only want to create music that will rely on the skilled hands of a DJ to really be effective—this doesn’t mean your song is made to be less interesting; skilled DJs search for these kinds of tracks as “tools” for their sets! When someone thinks a song is boring or too “simple”, I’d reply that usually it’s because it’s being listened to out of context, and someone like Villalobos or Hawtin could easily turn a simple track into a bomb by dropping it at the right time. I made an album on my label Climat that was quite experimental, and it was reported that Ricardo played some of the weirdest cuts in the middle of his sets and people would cheer…I doubt many acts can do that with a purely experimental track. That said, music that’s made for DJs to use as a tool has to be very clean from a technical point of view, which means that you need to have your sections very spaced out and have elements that come in repetitively at regular intervals. For example, your 4-bar sections could always end with a snare roll to indicate you’re finishing a section. This organization in your arrangement becomes a track that can be easily layered without confusion, for both the crowd and the artist.

If you think that most of your tracks are for DJs and are meant to be played in clubs, it’s important to test your tracks yourself in a DJ set to see how they go. You’ll want to determine if the tracks are easy to layer or not and to see what you can do with them.

When it comes to creating elements in a track through producing that can create tension, it’s essential to understand that tension rises as an expectation of something to happen (or not). If you write a song so that there’s a specific sound at a specific point every bar, if you have have a bar or two where you leave it out, this can create anticipation and tension. So from a technical point of view, there are some specific tension-producing techniques that can work well when implemented properly:

- Breakdowns. I’d say that techno between end the of 90s until about 2009 usually had at least one breakdown with “stuff” happening. Breakdowns can include things like cutting the kick out or removing lower frequencies—applied for about 4 bars or so—then a drop would follow. A few years after, people started to get really fed up with this approach, and many producers realized that it was actually more effective not to include a breakdown, and to let the DJs create their own breakdowns by cutting the lows at a moment better suited to their own personal set(s). That said, cutting the lows often still works well.

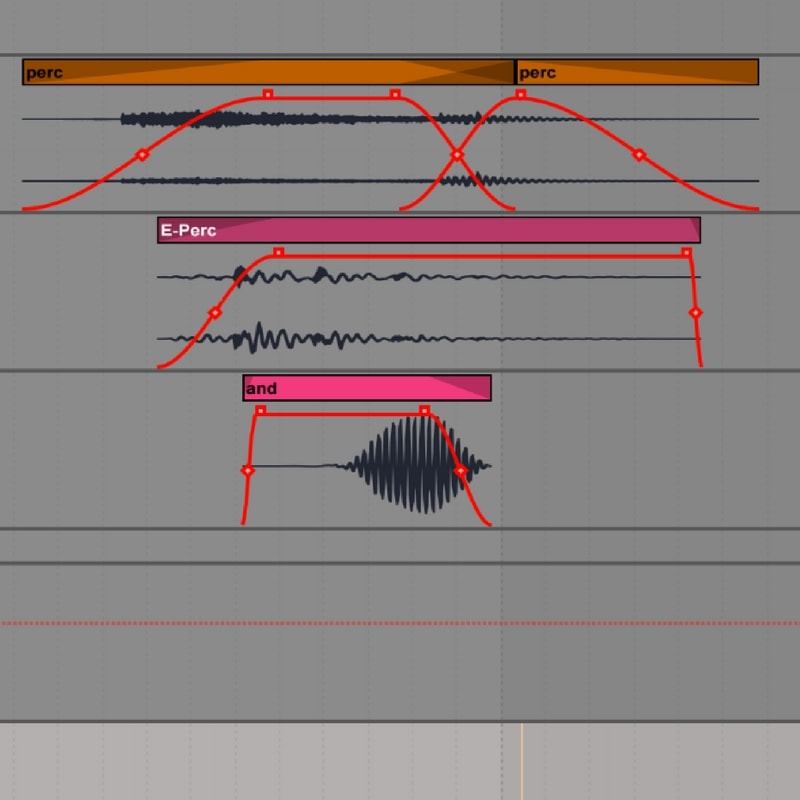

- Volume changes. When you introduce a new element into a song, you can either fade it in or simply drop in the sound at 100% volume. A fade will create tension as it the sound becomes louder and louder, while a drop-in is useful to create surprises, which is also a good way to resolve tension. One of the most misused techniques when it comes to volume changes is to have a variation in the volume of an entire section, then having the following section louder. When this is done properly, the contrast is a good way to create an explosion.

- Decay. Sounds that have their decay increase over time seem bigger and more powerful, especially if you approach changes progressively. Reverb use is also a way of adding decay, and if you add a very large one to short sounds, they’ll become longer, creating tension.

- From maximal to minimal. Having a lot of sounds happening at the same time and then trimming them down to the essentials will create an “emptiness” that people become familiar; they will anticipate resolution to a “fuller” mix. The density change is something that can be physically felt in a club setting. This is why everyone was using the white noise technique to create excitement for a while; it was a good way to resolve a moment of emptiness.

- Pitch. Playing with the pitch of a melody or sound is a good head trip, and if you play with it subtly, it can really create uneasiness and tension. Some genres use pitch manipulation in an extreme way by slowly modulating pitch to its highest point, but to me, this technique becomes irritating and predictable after a while.

- Pattern changes. If you’ve established your groove with a certain pattern and then introduce a hole or change, it will create tension.

Now, is there a particular duration for a tension-building section that might make it work better?

Yes and no. I’m lucky and have had the chance to hear and see many of my songs in a club setting. I’ve had many attempts at tension-building fail, and some succeed. Shorter tension-builders work better than longer ones. Also, keep in mind that some songs will play better if you don’t try to add tension to them at all. I think that 2-bar moments are great for tension-building because it also gives the DJs some time to play within them. If you make your tension-builder too long, you’re making the DJ work hard and potentially fail. Think about tension-building like a sauce—if it’s all premade, you have less room to add your own stuff. Don’t overdo it in your own productions; developing a sense of trust with the DJs who will be playing your work is essential. When people listen to minimal music and say it’s boring, it’s something I take with a grain of salt—perhaps at home in your living room it might be, but in the right context (such as a club), it might be more than enough.

SEE ALSO : Building a great groove

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!