Music Feedback: When to Take the Opinions of Others Seriously and When Not to Care

If you make music, you’ll get what I’m trying to explain here—the head space where you’re fully aware that it’s important to make music solely for yourself, but yet you really want to share it with the world, with other people who could potentially like it. If you love what you do, maybe someone out there also loves it, too?

Where should you draw the line between making music for others versus making it for yourself?

Honestly, it’s a tough question. The voice of reason in most people will answer it with something moralistic, like:

Making music for yourself is the way. Sharing is good, but don’t make a big deal out of what people say.

Unless you have a real mastery of your emotions, if you’re an artist, you will, at some point, want to share your work. If you share your work with “random” people, especially close friends or family, you’ll mostly get random feedback which can be confusing and hard to analyze constructively. Sharing your work is, at its most fundamental level, about seeking validation. Even old fart producers like me who have 20+ albums and have toured, still carry the need for validation. The difference I see between myself and younger artists, is that I carefully pick the people I share my music with—a way of knowing if you’re still relevant to people you trust. In past posts, I’ve explained how to network properly and how to build a circle of solid contacts.

A pattern I often see is artists having a very productive session, and the resulting track feels very emotionally powerful to them. Validation comes in when they seek to determine if the emotions in the session were valid, or if they were hyped over something bogus.

This sort of pattern results in an “they’re right, I’m wrong” thought process that causes cognitive dissonance. Let’s examine this pattern from a technical point of view:

- You make music absolutely for yourself, but this is artistic masturbation; it’s normal to want to connect with others to validate these feelings.

- The opposite is making music for a label, other artist, crowd, club, or festival, in which an artist is chasing other people’s opinions and lacks control over their own work—they usually end up frustrated.

If you ask someone for advice about music, sometimes people come at it from the problematic position of “I’m right, you’re wrong.” They’ll tell you what they think is good or not, based on their point of view. Sometimes people are not totally open to giving real feedback and will be biased. When most people are given the opportunity to criticize, they’ll find something wrong. It might not always be useful, but sometimes with music, particularly concerning technical aspects of production, there’s value in receiving good feedback.

When Should You Take Someone’s Feedback Seriously?

It’s up to you, but it’s heavily dependent on your ability and accuracy in evaluating your own work beforehand. Here are a few tips for evaluating your own work before seeking external feedback:

1. If your track creates emotion in you, never doubt it, even if it never reaches anyone. Not all tracks need to be released, heard publicly, or shared. You can make a song for yourself and perhaps a few friends—this is a totally valid way of making music. The “need” to release all your music is really a misconception that you’re entitled to be heard because you made a song. Honestly, you aren’t.

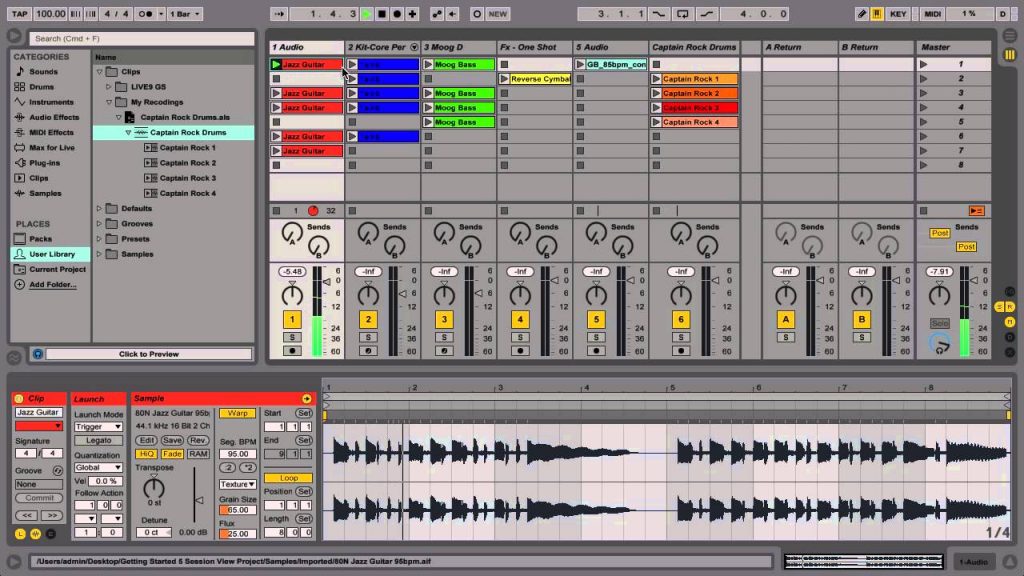

2. Listen to your song in different contexts to see what it feels like. For example, listen to it while commuting, in your living room, in your car, in front of a friend (in person!) or in the middle of your favourite playlist. This can reveal flaws in your work. If something feels off and you are limited technically, then you know that asking someone for feedback with a precise request should provide value to your work.

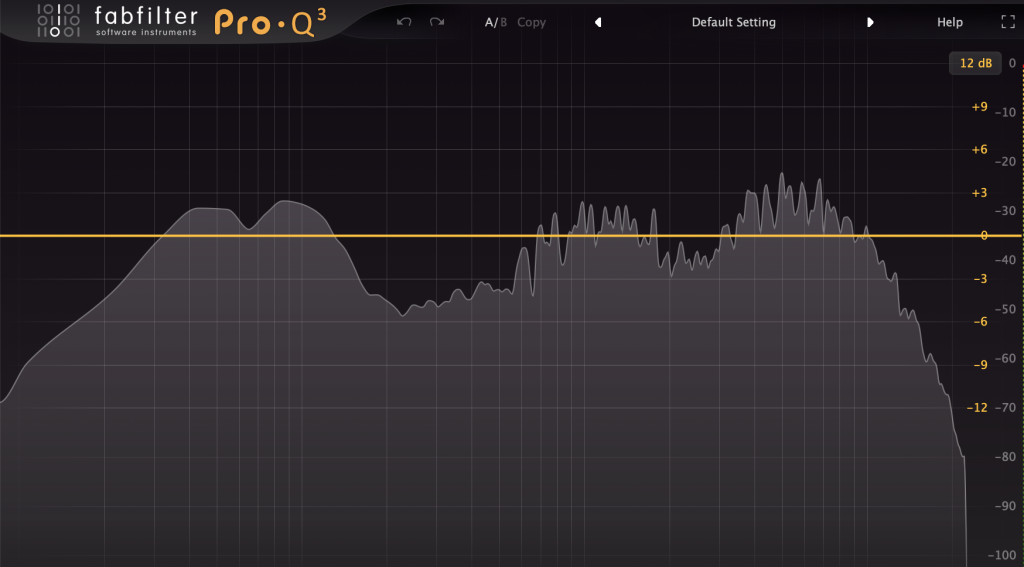

3. Use a reference tool such as Reference from Plugin Boutique which, if you compare your work with a song you like, you can easily see what is missing (tone or loudness). Fixing issues might be a roadblock for some artists, and that’s another reason it might be useful to get feedback.

Once you’ve done these three things, I’d upload a snippet to Soundcloud to get a reaction or share it privately with a few friends. I would never post music in forums without knowing what regular users are like in the first place. I also don’t share with close friends; they never get it and sometimes it can make the friendship awkward. I prefer having two circles of friends: music-related and non-music.

Never forget that it’s important to age a song for a few weeks or months, just like a wine, then come back to it afterwards—this trick reveals incredible details you can’t initially see or hear.

When is Feedback Disposable and Not Worth Taking Seriously?

- When someone implies that you should change something in the arrangement or sound design based on their tastes.

- When someone discusses some so-called “unwritten rules” about how music “should” be made (ex. you have to make all your sounds from scratch, you can’t use samples, etc).

- When their technical feedback is questionable. For example, some people might comment on bass without having access to a sub.

- When someone who lacks empathy can’t understand the vision of the track and tries instead to see it from their own point of view. For example, my ex never understood that music I made at home would translate differently in a club.

- When someone tags your music with buzzwords. Sometimes people would listen to a song and say “oh, it’s chill” but not understanding that on a large system, it might groove.

- When you receive comments such as “X is good” or “X is bad“. As if the person had the universal understanding of some permanent elements in music—such comments don’t mean anything at all. We all know that if person X finds it bad, person Y might think it’s genius.

I hope this helps you understand what type of feedback is worth taking seriously!

SEE ALSO : Common mindsets of musicians who have writer’s block and how to solve them