How to maintain consistency in the quality of your productions

The most consistent musicians have reached a comfortable flow and they finish tracks that they’re satisfied with fairly quickly. But how do they ensure that each of their tracks are maintaining the same level of quality as their first well-received works, as they complete more and more of them?

Making a lot of songs/tracks and actually finishing them is, to me, one of the most essential purposes of making music. Stalling on a particular idea or song builds up doubts, and eventually you’ll grow to hate it. If you finish up a track quickly—as opposed to more slowly—you capture an idea you liked at a precise moment in time and make the most out of it, then move on to the next idea.

FACT: you will always learn something new when you finish a song that you can apply to the next one.

The faster you become at completing tracks, the more you become articulate in your self-expression; if you dig a really good idea, you’ll know what to do pretty quickly to make the best out of it.

Many well-known and consistent artists make multiple songs (yes, songs!) in one day. Marc Houle, Ricardo Villalobos, and Prince to name a few, have expressed that they like to sit, jam, record, edit a bit, and then move on. Ricardo’s long songs are actually long sessions that haven’t been edited. “It’s more important to simply record something each time you hit the studio rather than make a perfect song“, I’ve heard him say.

How do you maintain consistency in your work when you’re creating a ton of tracks?

My personal mentality that I like to have is to not get too attached to the music I make, nor about its potential or future. With this mentality in mind, you can embrace imperfection, have more relaxed sessions, and have more fun. But yes, there are also some technical points you can keep in mind to avoid letting your work slowly degrade in terms of quality while trying to maintain a regular quantity of completing tracks:

- Stay away from trends or gimmicks. Trends can be hard to spot when they’re first evolving, but usually there are signs. When many people use the same samples over and over, which can often define a style, you know that’s a road probably too often taken—in going there yourself, you might get lost in the sea of similar sounding songs. To me, production trends are about some samples, effects, and arrangements that become a norm. I’ll always remember a long time ago when I was into hard techno, I was at the record store listening to a pile of 30 records and every record had the exact same structure to the point where you could predict when the kick muted, the hats came in, and so on. Sounding like existing trends is not a good way to stand out as a memorable, original musician; timeless music is often “odd” when it’s first released, but something catchy about it makes it work.

- Use scales. You don’t always have to be using an established scale when writing, but it will help your music age a bit better. Off-scale or highly dissonant music not only sounds a bit weird or off-putting to the average listener, but by working with established tonal scales people can reference your music decades later. When I think of high-quality music, the musicality in terms of scales is always top notch. If it’s purely experimental and still high-quality, it’s usually based on a concept that makes it relevant.

- Cross validate with references. I can never stress this enough—your references, loaded in a playlist alongside your music, should feel right.

- Have a friend as quality filter. A reliable friend is one that will tell you when things aren’t working. I personally like to have 5 people to send my music to in order to get reliable feedback. Sometimes I feel more excited sending them my music than submitting it to a label. You should have 5 responsive people that want to listen to your stuff; proper feedback is a great feeling when done right.

- Keep your renderings/bounces at -6dB, 24bits. This is in case you want to release them in the future, but also because music with headroom is universally more well-received. Back when the trend was to have very loud mixes, your music was irrecoverable later on if you lost the original mix. Loudness has also aged terribly since this trend went out-of-style.

- Use quality samples and quality tools. What makes a great mix is the use of great samples. Working with a harsh sample means you have to use more effort to make it sound better, but the end results could still bad, or even worse.

- Simplicity ages best. Humans tend to remember simpler ideas. Complex intentions and complicated, draining music isn’t always the best in the long-run. I’m not saying “don’t do it” if you’re into it, but maybe to tone things down a bit if you’re interested in the longevity of your work. I’m in love with this quote by Da Vinci: “simplicity is the ultimate sophistication.”

- Make sure your mixing is high-quality, and use quality effects. If you can make sure your song is properly mixed, it will certainly age much more gracefully. Otherwise, you might regret some decisions you made in your mix as it ages. Cheap effects and presets don’t age very well because others might also use them heavily. Further down the road, your originality might feel lacking as a result, and plus nothing ages worse than a gimmicky sounding effect (ex. think of cheesy effects used on audio in the 80s.)

The effects of your work habits on maintaining consistent quality in your work

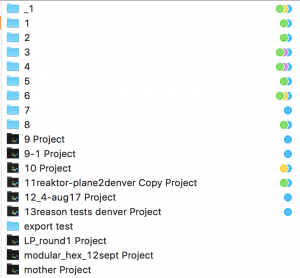

There are things you can do to make sure all your tracks end up with a level of quality you are happy with and will continue to be happy with as they age. I believe that working on multiple tracks at once is a great way to maintain perspective on your quality levels. Personally, I also like to export half-completed tracks and listen to them later, or import them into the next track I’m working on to give myself better perspective(s). Sometimes, I encourage clients to bring in all the tracks they’ve made in the last few months so we can toggle between them easily and make comparisons—this task might reveal a lot to you regarding the patterns and trends you use the most.

Another signpost I’ve used was a sort of music “target” I set through Ricardo Villalobos. I’d study his music, his sets, and a recurring question I had was “will he play this track of mine?” There wouldn’t be any goals attached to this besides, perhaps, having him play my music, but it was more as a reference point of how my music could be made or adapted,

Another signpost I’ve used was a sort of music “target” I set through Ricardo Villalobos. I’d study his music, his sets, and a recurring question I had was “will he play this track of mine?” There wouldn’t be any goals attached to this besides, perhaps, having him play my music, but it was more as a reference point of how my music could be made or adapted,

Filtering ideas into a concept

Filtering ideas into a concept

View/purchase via Amazon

View/purchase via Amazon View/purchase on Amazon

View/purchase on Amazon View/purchase via Amazon

View/purchase via Amazon View/purchase via Amazon

View/purchase via Amazon

Legato: This is probably the most useful thing to activate for clips in variation. Basically, the Legato option will let the selected clip to take over the one that was previously played, based on the quantization you have set. So for instance, let’s say you play a hihat clip, then press the first clip of the variation. It will stop the activated clip and immediately switch to the other one you just started. On the image, I have set it to 1/16, meaning it will be played on the next 1/16th, keeping it on tempo. Keep in mind that the variation clips are “in sync” with the one playing so that it will continue at the same position in the clip. If legato wasn’t activated, it would start at the beginning of the clip.

Legato: This is probably the most useful thing to activate for clips in variation. Basically, the Legato option will let the selected clip to take over the one that was previously played, based on the quantization you have set. So for instance, let’s say you play a hihat clip, then press the first clip of the variation. It will stop the activated clip and immediately switch to the other one you just started. On the image, I have set it to 1/16, meaning it will be played on the next 1/16th, keeping it on tempo. Keep in mind that the variation clips are “in sync” with the one playing so that it will continue at the same position in the clip. If legato wasn’t activated, it would start at the beginning of the clip. Intensity Variation: If you want to quickly go from open hihat to closed one, one of the fastest way is to play with the “Preserve” section and set it as in this image. Playing with the percentage will let you adjust how much of the end of each sound can be preserved. Having it at 100% is fully open and let’s say 25% is more closed, building tension. So one variation can be set low at first and then the other ones can be more open. If you see the need to boost the energy quickly, then you can go in one of the variation.

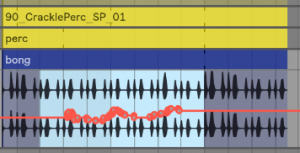

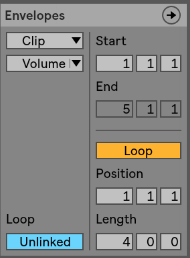

Intensity Variation: If you want to quickly go from open hihat to closed one, one of the fastest way is to play with the “Preserve” section and set it as in this image. Playing with the percentage will let you adjust how much of the end of each sound can be preserved. Having it at 100% is fully open and let’s say 25% is more closed, building tension. So one variation can be set low at first and then the other ones can be more open. If you see the need to boost the energy quickly, then you can go in one of the variation. Envelopes: Super useful for variations as well because you can create automation on a very small scale or a longer one. Many artists will use this on EQ to give life to a clip and making sure it feels like it is alive. The important part is to make sure that the envelope isn’t linked and then you can decide of the length of the automation, on one attribute. Tip: make sure you select “Clip” in the first drop down to make sure the changes are made in the clip itself.

Envelopes: Super useful for variations as well because you can create automation on a very small scale or a longer one. Many artists will use this on EQ to give life to a clip and making sure it feels like it is alive. The important part is to make sure that the envelope isn’t linked and then you can decide of the length of the automation, on one attribute. Tip: make sure you select “Clip” in the first drop down to make sure the changes are made in the clip itself.

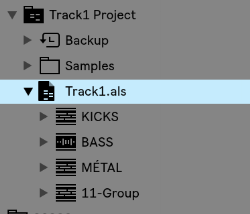

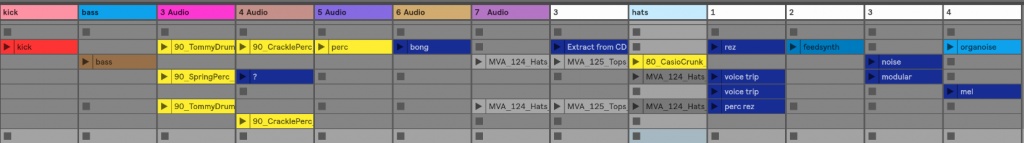

Next we will import all songs into that project. There are two ways to do this and it’s up to you to decide what is the best for you. I personally like to open a track, grab all clips in the session, copy (cmd+c), then open your “My Live Set” project and paste. You can also copy through the browser and should you be more comfortable using that method, do it that way.

Next we will import all songs into that project. There are two ways to do this and it’s up to you to decide what is the best for you. I personally like to open a track, grab all clips in the session, copy (cmd+c), then open your “My Live Set” project and paste. You can also copy through the browser and should you be more comfortable using that method, do it that way.

1. The Hook

1. The Hook 2. Sound design

2. Sound design 5. Structure/Arrangements

5. Structure/Arrangements