Creating Depth in Music

I don’t know many people who took theatre in school, or aspired to become an actor or comedian. For me, having a background in theatre has shaped my vision of music, performance, and storytelling. In Québec, we have a “theatre sport” called Improvisation, where teams meet in a rink to create stories and characters, out of the blue. After practicing this for 20 years or so, it’s shaped how I perceive songs and sets. There are so many parallels to music in theatre: how a story develops, the use of a main character, supporting roles, etc., all of which can be applied to the use of sounds in a track.

A story is never great without quality supporting roles. Support adds depth to any story, and richness to the main character. Think of all the evil nemeses James Bond has faced—the more colorful they were, the more memorable the story, and the same goes for songs.

You might have a strong idea for your song, but if it has a good supporting idea or two, then you’ll end up with a song that keeps you engaged until the end.

I’ve been really into minimalist music lately; I like music that has a solid core idea that evolves. I was reading a really nice post on Reddit about Dub Techno where one of the main criterion discussed was the importance of simplicity. Simplicity doesn’t make something dull or dumb—in music it can be a reduction of all unnecessary elements, in dub techno resulting in a conversation between the deep bass and the pads and other layers.

If you’re immersed in electronic music, you’re generally used hearing multiple layers and often multiple conversations between sounds. Percussion layers will be often related to themselves, but the main idea is usually supported by a second layer. I often hear this in some indie rock songs too, especially ones that have some electronic elements in them. The way the human ear works, is that we will always hear the main component of a song as the centre of attention, but attention will shift back-and-forth between different layers. The advantage of having depth in music is that it encourages repeat listening. For a listener to replay a song and hear something new is exciting; some songs will grow on them even though they may have felt overwhelming during the first listen.

How can you create secondary ideas and “supporting roles”?

There are multiple ways to do to add depth to your songs.

Negative Space

The most important part when you program or write a melody, is to leave some empty space in it, which I call “negative spacing.” This space is where your secondary ideas can appear, supporting or replying to the main idea. I usually start by writing a complex melody, and then will remove some notes that I will use elsewhere, either in a second synth, bass, or percussive elements. Here are some suggestions as to what you can do with the MIDI notes you remove from the first draft of your melody:

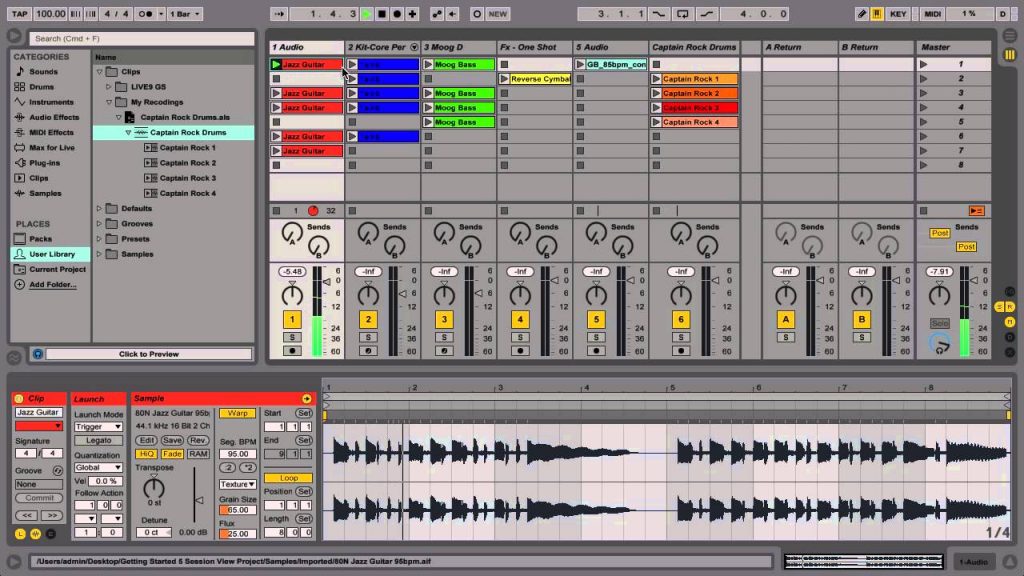

- Use the same MIDI notes from your melody, but apply them to multiple synths or other sounds to create variations and multiple layers that all work together.

- Use the MIDI tool chords and arpeggios to build evolving ideas that come from the same root.

- Look into some MIDI-generating Max for Live patches that can give you alternative ideas. I’ve had some fun with patches like Magenta, but also with the VST Riffer or Random Riff Generator which are really interesting.

The “Fruit of the Tree” Exercise

This is an exercise that is a bit time-consuming that I have a love/hate relationship with. You spend time playing the main idea through intense sound altering plugins. So, if your main idea is a melody, imagine you send it through granular synthesis, pitch-shifting, a harmonizer, random amplitude modulation, etc.—you’ll end up with a bunch of messed up material that can be shaped into a secondary idea while still being related to your original idea. The idea is to transform what you have into something slightly different. There are multiple plugins you can look into for achieving this:

- Vocoders, mTransform, mHarmonizer, mMorph: These all work by merging an incoming signal and with a second signal. So, let’s say you have your main idea or melody—you can feed it into something completely different, such as a voice, some forest sounds, textures, or percussion, and you’ll obtain pretty original results.

- Shaperbox 2 is the ultimate toolbox to completely transform your sound by slicing, gating, and filtering it, with the help of LFOs. This is pretty much my go-to to create alternative tools quickly. One thing I like to do a lot, is to run two side-by-side on different channels, and then use them to create movement that answers one another. For instance, one will duck while the other plays. You can also use side-chaining in the newest version, which can create lovely reactivity, if you use it along with the filter to shape the tone by an incoming sound. This allows you to do low-pass gating, for instance, which isn’t really in Ableton’s basic tools.

Background Sounds

The lack of background sounds, or noise-floor, always leaves people with the impression that there’s something missing in a track. This can be resolved with a reverb at low volume that leaves a nice overall roundness if you keep it pretty dark in its tone. Low reverb creates an impression that a song is also doubled, or wide. Another good way to make background sounds is to load up a bunch of sounds that can be played multiple times in different sections of your song, at very low volume. I was checking out this producer who does EDM/festival music, and he would use sounds of people cheering at a very low volume in moments where the chorus of the song would hit, to create more density and excitement. However, at a high volume, this approach can conversely create a “wall of noise”, so it should be crafted carefully.

If you simply drop a background sound into a project, such as forest sounds, you’re missing out on one of the most enjoyable activities in making music, which is to create your own live sounds. A forest has a bunch of—what seems like—random sounds. You can alter this, and say have a basic 5-second background of noise-floor and then decide when the bird chirping comes in via automation and perhaps have them sync to the tempo. This creates a bit of a groove too. A good exercise is to try to create sounds that emulate nature as you’ll have a bit more control over the sounds (and you’ll learn more about sound design in the process).

Ghost Notes

Ghost notes are mostly discussed as they relate to percussion, but they can be used, as a technique, with anything. A common example of ghost notes is their use in hi-hats, as a bunch of in-between hats at a very low volume to fill up space, which stretches the groove and but avoids too much negative space. Aside from using this technique on the low end—where sounds need a lot of space and room to breathe—make sure everything doesn’t sound mushy. The use of a delay in 16th or 32th notes can be a good way to create ghost notes.

A tap delay, where you can program where the delays fall, is also super fun in terms of creating ghost notes, as you can use one to make complex poly-rhythms. However, I suggest cutting some part of the high-end from the delays to avoid clashing with the main transients, and make sure the volume is very low. Using a AUX/Send bus for delays can be quite useful.

SEE ALSO : Improving intensity in music