Service Update: Track Finalization Is Now Exclusive

It’s been a hard decision to make since I’ve enjoyed collaborating on so many tracks that have been sent to me through the track finalization service that I offer. However, I have found that by just allowing anyone to purchase this, it becomes not only a source of a great deal of stress but also the work to reward ratio often doesn’t pan out. Therefore, I am indefinitely pausing my track finalization service, except for people with who I have enjoyed working with in the past.

However, rather than just pausing the service, I feel like I owe an explanation. This blog post will be a little different than most and will have two authors. First, I’ll explain my reasoning, and then someone who has used my service a few things will explain his thoughts on working with me.

Pheek’s Perspective

I have clients that have standards that are pretty high, which I have no problem with. I’m happy to help. However, paradoxically many producers come to me and love their track just how it is. Yet they still want me to work on it. This is confounding to me, because if you love your track, why do anything else to it? Music is subjective, and in the ear of the beholder, so it will never be great to everyone. The only thing that matters is if it’s great to you.

However, they still hire me and have a track that they are emotionally invested in because they have put so much effort into it. They just want the track to be perfect, so they think that I can do this, which isn’t true. Hiring an engineer won’t fix everything, and transform a piece into the hottest track to hit their respective Beatport chart. And while this sometimes may happen (usually by pure luck), engineers can only fix what we are allowed to, and often have to contend with people’s cognitive bias’ towards their track.

Therefore, with these clients, it’s necessary to communicate that nothing is perfect and that the concept of perfection, especially in art, is folly. To be fair though, as an artist, this concept took many years to accept. I eventually realized that no matter how much I tackle imperfections, the end result is often staleness. And staleness is something that nobody who is writing art-focused music wants since it’s these imperfections that make songs exciting. It’s these imperfections that make them human. And humanity, especially within electronic music is sorely needed since the criticism from detractors is often that electronic music sounds too engineered, or robotic.

This pursuit of perfection messes up my client’s workflow because they are often obsessed with having the perfect track rather than just finishing them. To me, this is essentially chasing unicorns in a field of chocolate, because, like I said before, perfection is a fantasy. Still, this mindset persists in many since people set standards for themselves that can’t be easily changed.

Now, a perfectionist mindset would be fine, if it was tolerable. However, after all these years of consulting, I’ve noticed that perfectionists always comes with one personality trait – they’re micromanagers. And let’s be real here when was the last time you heard someone praising a micromanager? Probably never, because it drives everyone crazy.

The end result is usually two things: they will either say that the track is too close, or different from what they gave me initially. However, I usually don’t know which one it is until after I submit the track back to them. They reply with what else needs to be fixed, so I go and fix it, which I’m happy to do because there is no way I’m going to get it right the first time unless I’ve worked with them before. However, quite often, I spend hours going in a loop and reverting it back to pretty much exactly what they gave me in the first place. Or they will ask for so many additions that it eventually warps the track to a point where it doesn’t match the patterns they have set in their own heads. If you’re a producer, you know what I’m talking about – you can anticipate what is going to happen before it happens and if you miscalculate that, or if it’s different, it creates cognitive dissonance.

This cognitive dissonance is because producers are emotionally engaged with their tracks, and they have heuristics in their mind about where things should be in the mix, or compositionally. They EQ’d it a certain way, they didn’t have certain effects or compositional elements in it that are now in it, so when they hear it, it is jarring, because they expect it to be a certain way. Therefore, it doesn’t sound “right” to them.

However, more often than not, a producer’s home studio is not representative of the outside world, so it’s no wonder that it doesn’t sound “right” to them. But since they are so wrapped up in it, they ask for more modifications, without realizing that what they are asking for is actually incorrect. However, this sometimes forces me to go back to how it was, because of their inability to realize that the reason why they hired me in the first place was to provide them a track that translates well across all systems.

This happened again recently, where the producer lamented that it didn’t sound close enough to their reference track, which they never provided. So I asked them to send that over, and lo-and-behold, the reference track wasn’t properly mixed. Now, I happened to know this artist pretty well, so I provided them with a reference that was correct. Strangely enough, I haven’t heard back from this client.

As you may have surmised, I’m not a fan of doing business this way. Therefore, from now on, track finalization will only be available to people I’ve worked with successfully in the past. Because at the end of the day, why would you want someone to finish a track that isn’t on the same creative wavelength as you?

Alex Ho Megas’ Perspective

Ok, so none of you know me. However, I’ve been doing marketing for Pheek for almost a year now. And sometimes we trade services, and one of those services is track finalization. He asked if I would write something about my experience working with him on this since we have done it a few times. You may be thinking, “how can someone be unbias towards their client?” The answer is, I really can’t. However, I’m going to do my best to explain what working with him is like.

Reading Pheek’s perspective above, I intimately understand the cognitive dissonance that comes from having your track modified. You do expect certain things to be in certain places, subconsciously. Consciously, I know that they are most likely wrong since I don’t have a tuned studio and an acute knowledge of mixing and mastering. I, personally, just like writing music and designing sounds.

One thing we often agree on is that music is usually a collaborative process and that electronic music is one of the only genres where it’s often not. Therefore, I hire Pheek knowing that collaboration often leads to better music. So you know, I’m not always immediately happy with everything I get back. I just know to give it time and to send it off to people that I trust to provide feedback. Then, I think critically about it and note things I would like changed.

For instance, sometimes I notice that the tuning on a sample is incorrect, or that an element needs to either be extended or shortened. Sometimes there are parts that I want to have emphasized that Pheek deemphasized, like how a snare hits at a transition. So I confer with him and ask if it makes sense to change those things. Often he says they can be changed, however, I always make sure to just trust that 1) my room is incorrect and 2) that a new perspective is helpful. Sure, sometimes I override his recommendations, but only after careful consideration. And to be fair, I still could be wrong about those decisions, but as he said earlier in this post, music is subjective in many ways.

I would say that the most difficult one we’ve worked on was the last one we did. Right from the beginning, there were some warping errors that made the channels not properly align, and therefore significantly changed the composition of the track. This was hard to explain because he was not familiar with the track, so he couldn’t figure out what was wrong. To him, of course, it’s correct, why wouldn’t it be? However, I just pointed him to a time in the original track where it was wrong, and had him compare it to the version he sent over. It took some time to figure out an effective communication method on this, but ultimately, we got there.

Then he added a bunch of foley sounds to the track, per my request. However, they were either too maximalist or minimalist, so I asked for a modification. These weren’t exactly what I was looking for, so we went back again. Being content with what it was, I sent it in for a mixdown. Then I sent the mix to another engineering friend to see what he thought of it – and it didn’t think it was right. So I just asked Pheek to bounce down the stems and send them over so I could see what my friends sounded like. Funny enough, after comparing the two, I prefer Pheek’s and will use his version when it’s eventually released. This example just goes to show that this track had a particularly strong hold on my perceptions, which makes sense – I worked on it forever. It was only after a good amount of time that I was able to crack these biases.

The best recommendation I have about his track finalization service is to make sure to clearly mark where there are things that need to be changed. Note the time, note the duration. Make sure to have a copy of the old track handy that you can send him so that you can point to when you need things reverted. Make sure to mark the times and durations on those. He has a blog post about “how to communicate with an engineer,” which provides tips that will smooth the process of working with him on track finalization. However, it seems like now, he’s only working with people he has vetted in the past. So if you’re reading this, and have successfully done track finalization in the past, I recommend reading this article.

Another good thing to read would be his post on finalizing tracks on your own now that the service has been made exclusive to previous clients,

One of the most revered electronic albums of the last decade is Jon Hopkins’ blistering techno/neo-classical masterpiece,

One of the most revered electronic albums of the last decade is Jon Hopkins’ blistering techno/neo-classical masterpiece,

First, know your music. Whatever genres you listen to, please get to know what it has and needs. If you read this blog regularly, you know that I always insist on knowing and using references. The mothership method also starts with references. There are a few essential questions you need to ask yourself when you listen to your references:

First, know your music. Whatever genres you listen to, please get to know what it has and needs. If you read this blog regularly, you know that I always insist on knowing and using references. The mothership method also starts with references. There are a few essential questions you need to ask yourself when you listen to your references:

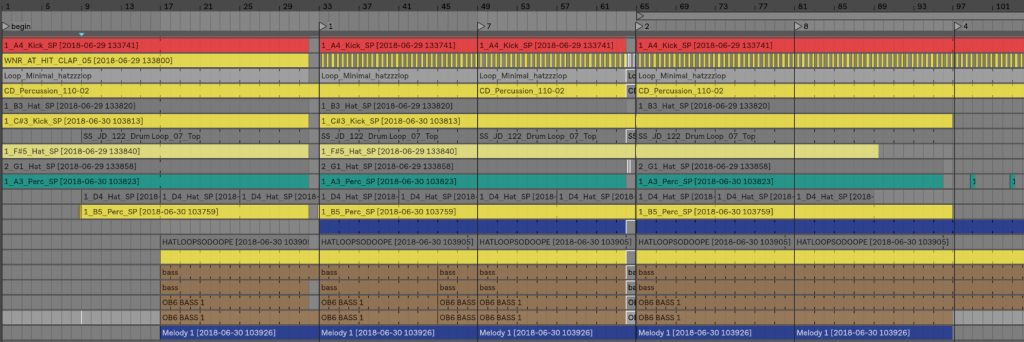

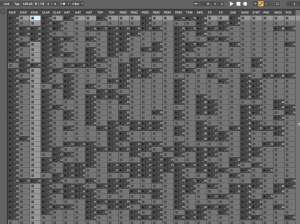

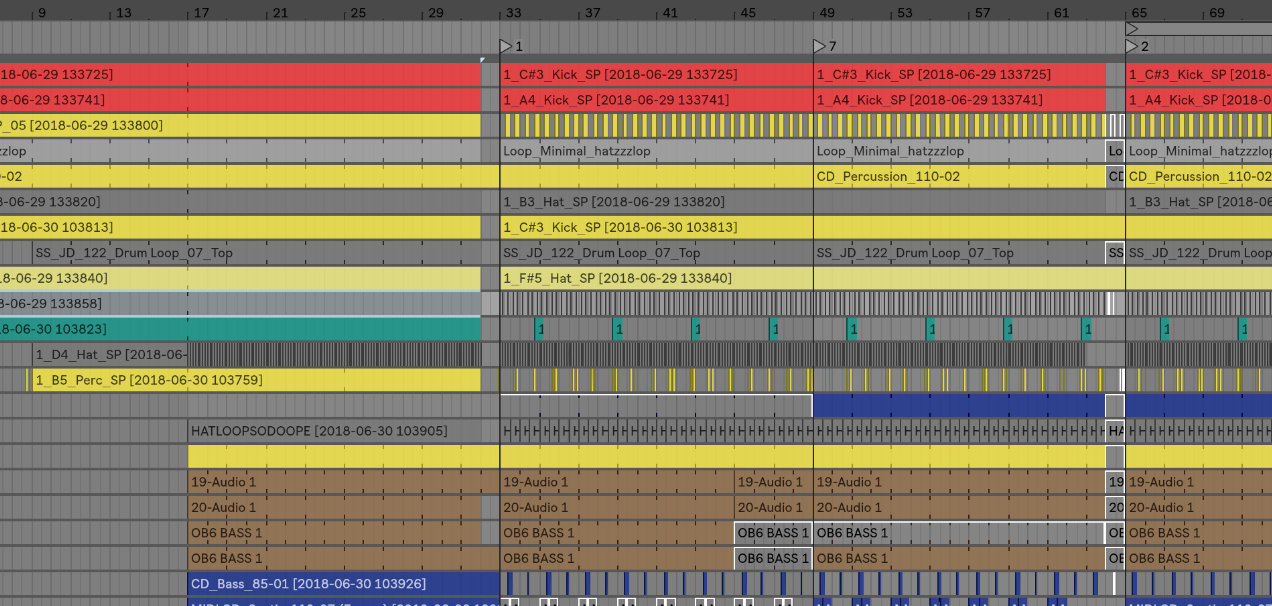

Before consolidation

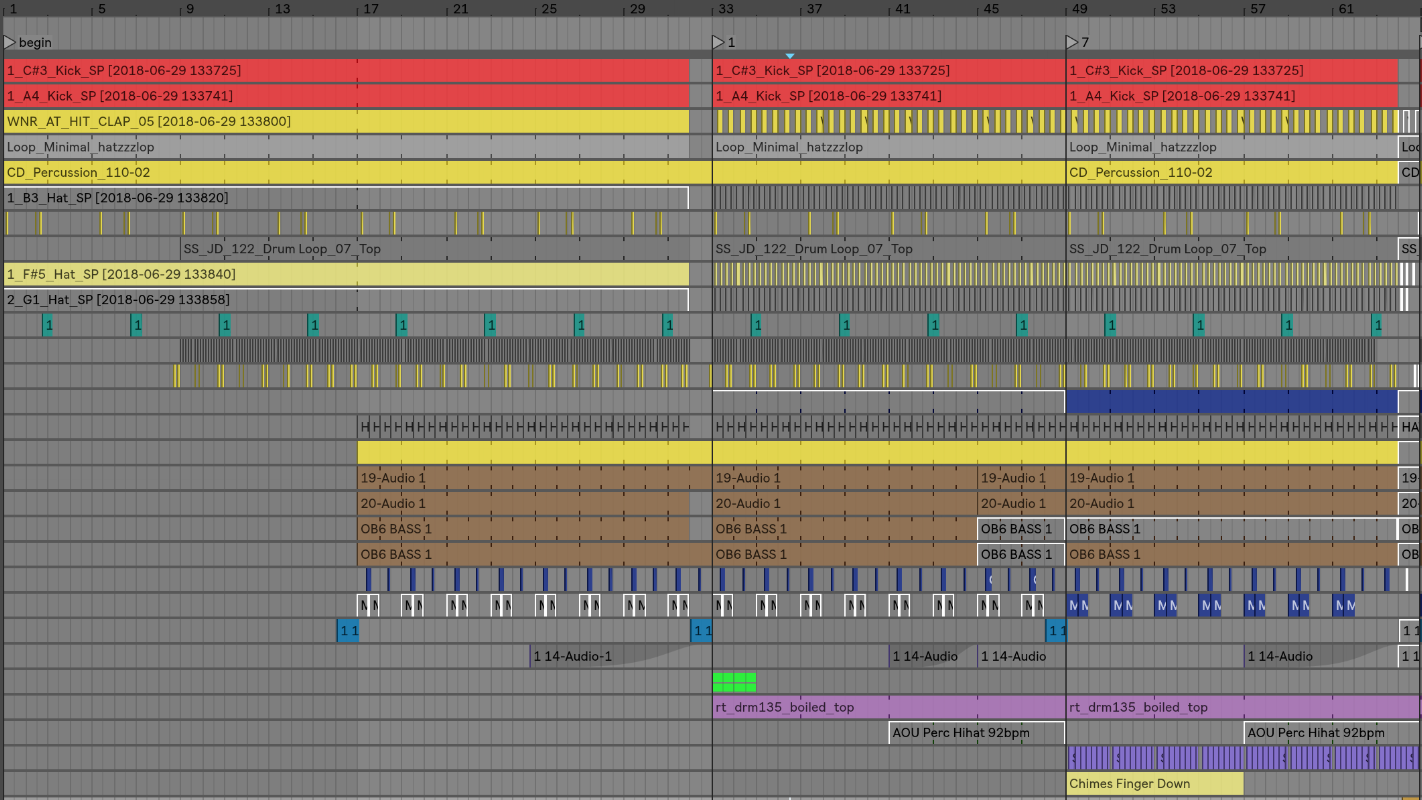

Before consolidation Clips consolidated

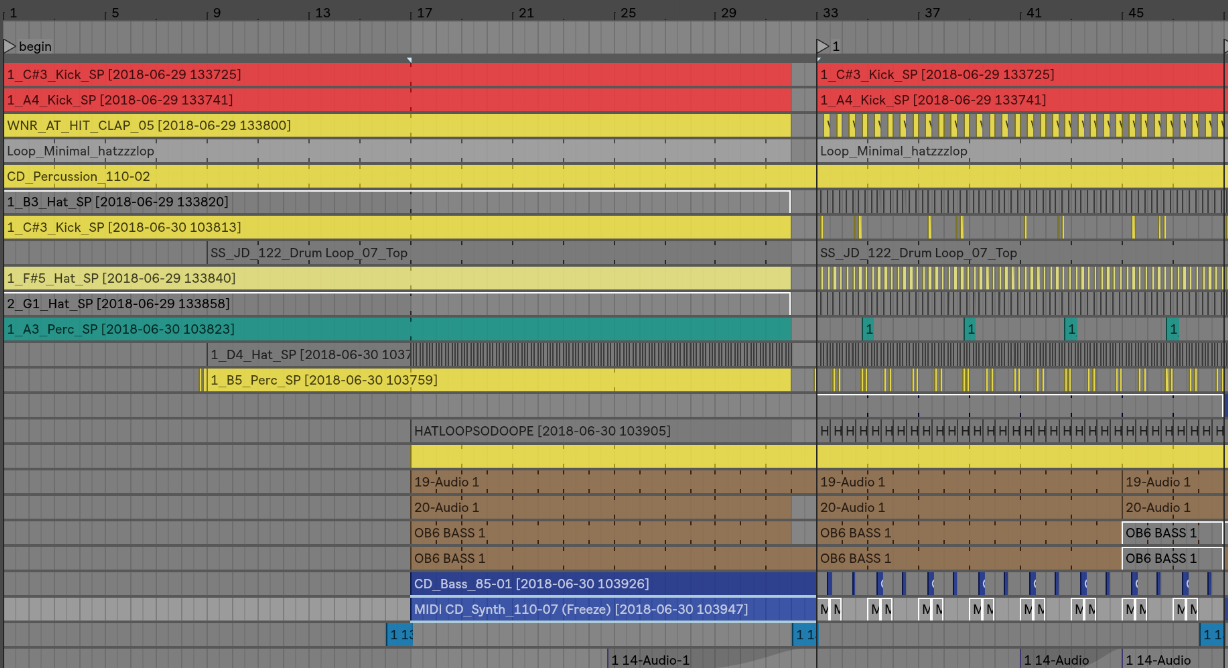

Clips consolidated And duplicated

And duplicated