The Art of Keeping People on Their Toes

You know when you discover music that breaks the mould, and you can’t stop listening to it? When there’s just something special about it that keeps you playing it on repeat? There are actually certain recipes for giving music its power, and a lot of it has to do with keeping people on their toes. Here are some techniques for keeping your music fresh and innovative.

Known and new anchors

Genres are largely distinguished by a specific set of sounds, rhythms, or structural arrangements. For instance, deep dub techno has its signature rich pad sounds that you won’t really hear in, say, trance music, which is more known for the heavy use of arpeggiated synths. Some deep house uses the same  pads as techno, but you can still differentiate the two because of its structure and percussion samples.

pads as techno, but you can still differentiate the two because of its structure and percussion samples.

When producers want to create in a specific genre, they’ll sometimes repeat what has worked before by getting all the sounds right. If you stick to the tried and true though, you’ll need to really up your game to get noticed because you’ll be repeating the same old formula.

Introducing sounds that are less common to the genre can be a great way to shake things up. You could bring in foreign percussions that aren’t usually associated with the style, or samples that might throw people off. New anchors, or a sense of novelty, always create interest for listeners.

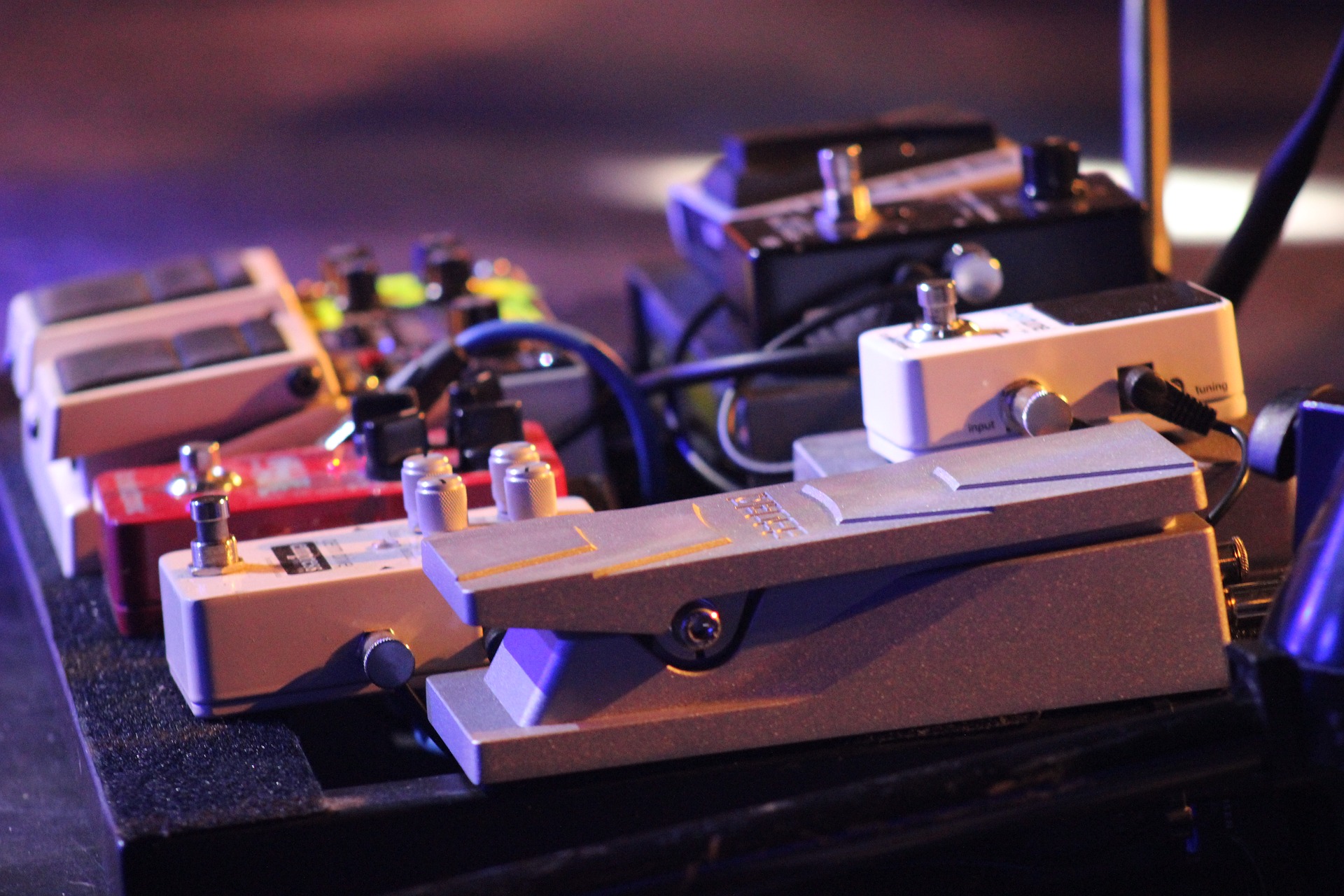

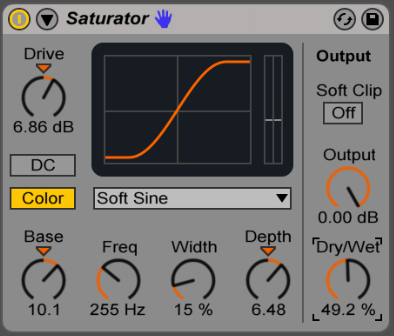

Technological novelty

I follow a few sites religiously to keep up with the latest news about new effects, DAWs, and the like. Keeping current lets you get ahead of the curve and stay fresh and innovative. This might sound like a silly example, but people like Cher in her hit “Believe”, or Daft Punk with “Around the World”, showed how using forward-thinking technology at the right time can help you make it huge. You might go “meh” at those songs today, but when they came out, it was a big deal.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yca6UsllwYs

Balancing surprises

If you browse the web for information on what makes music addictive, you’ll read that the brain seeks out elements that balance predictability with a sense of surprise. If you’re kept just slightly off balance, but still feel you’re on stable ground, you can get the dramatic sense of venturing on some sort of journey while facing obstacles you can overcome. Many people experience a sense of travelling when listening to music, and it’s even been shown that music can produce some of the same hormones as ingesting drugs.

If you’re creative with them, these common production-related tips will help you generate tons of new ideas:

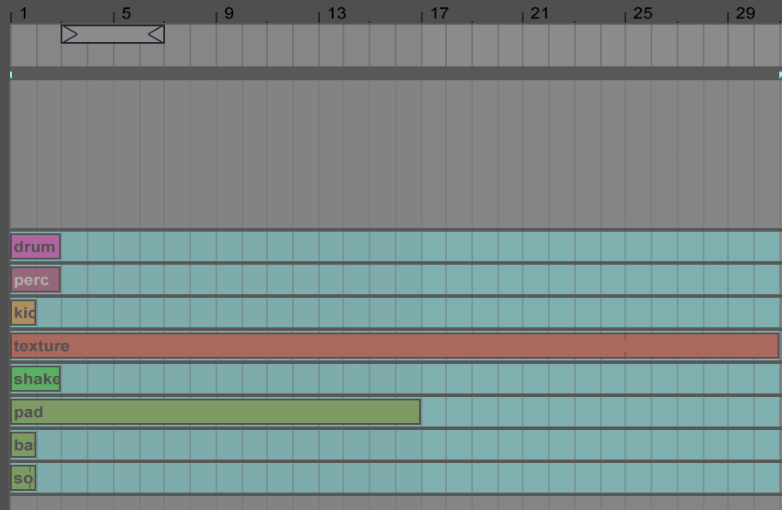

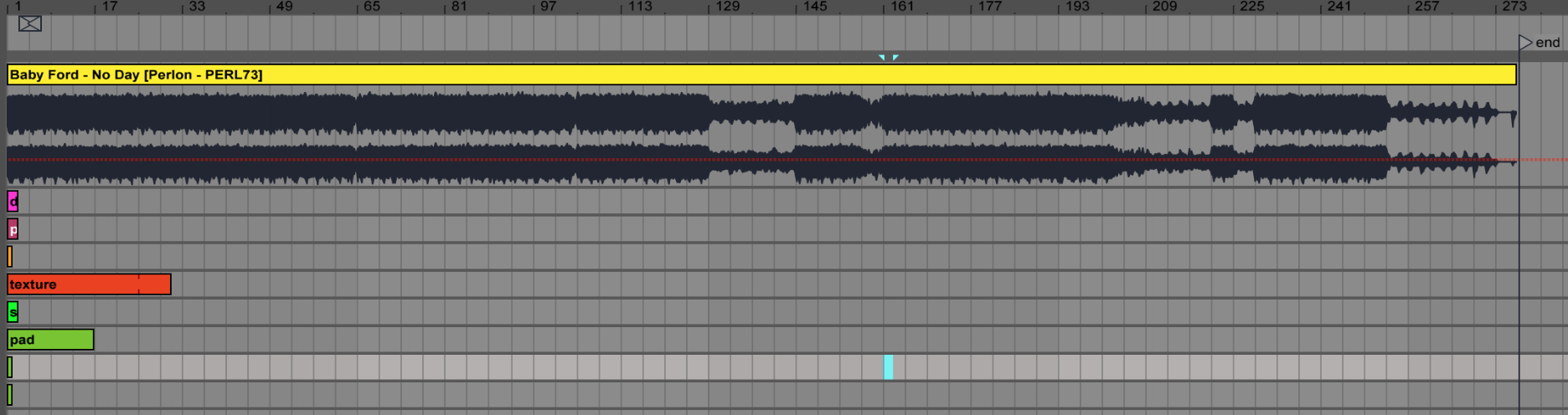

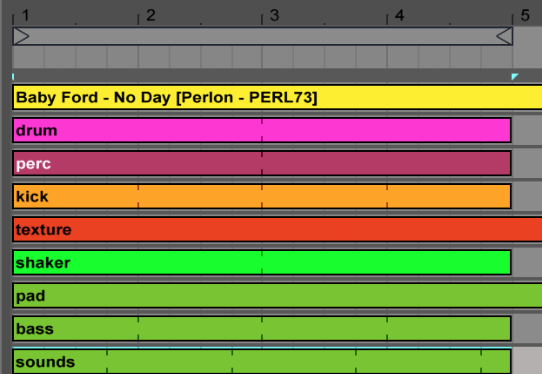

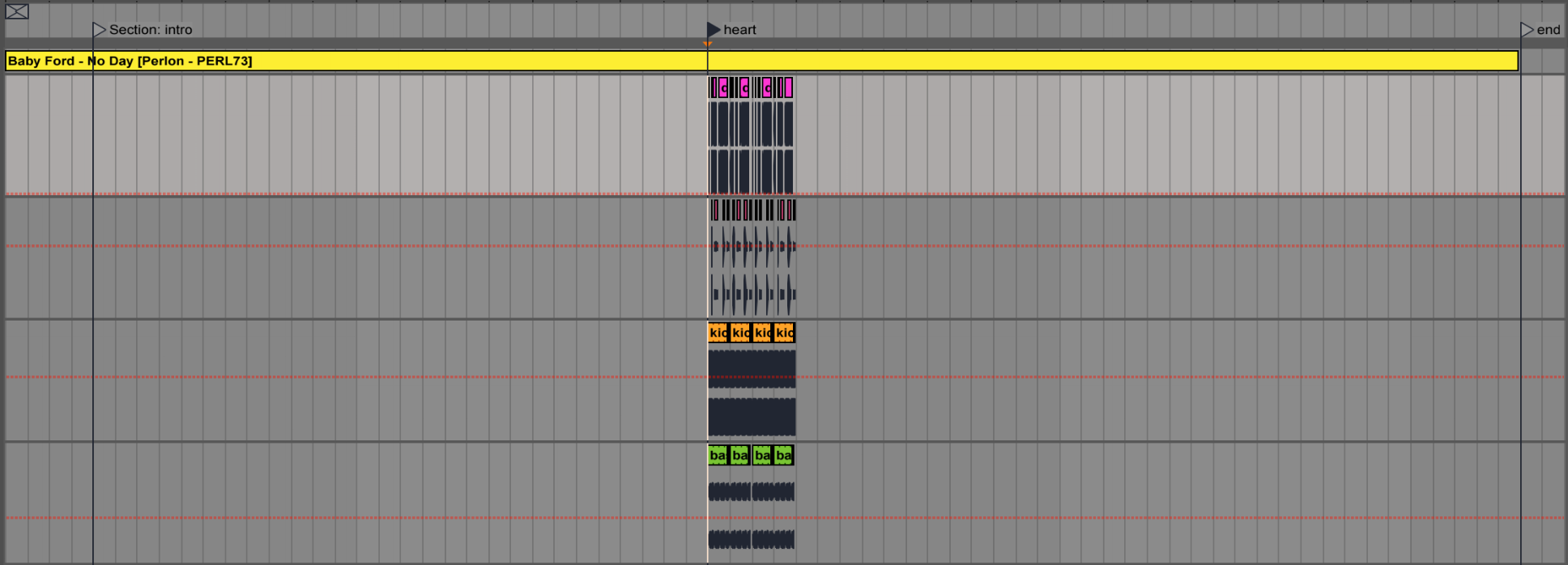

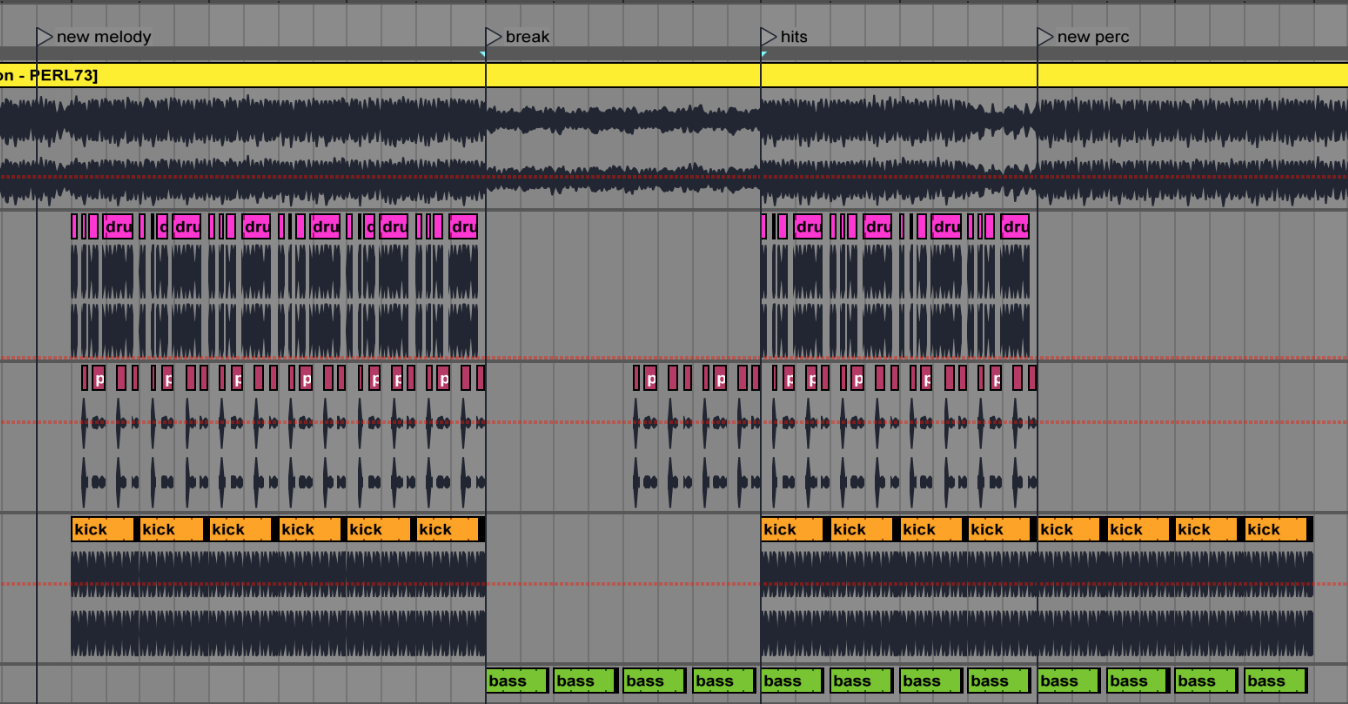

The 1-2 punch technique. I’ve been doing theater for years, and this popular trick is used to surprise people or make them laugh. I’ve noticed how it’s used in movies, advertisements and of course, music. The idea is simple: you produce a cool idea, trick or sound that pleases or surprises the audience. This sound or idea should be one of the main elements of your song. After a certain while, you’ll repeat it a second time, which generates a sense of satisfaction in the listener. Wait a little while longer, and on the third time, when the listener is expecting it to repeat again, you deliver either a different sound or a new variation to throw them off. This usually never fails.

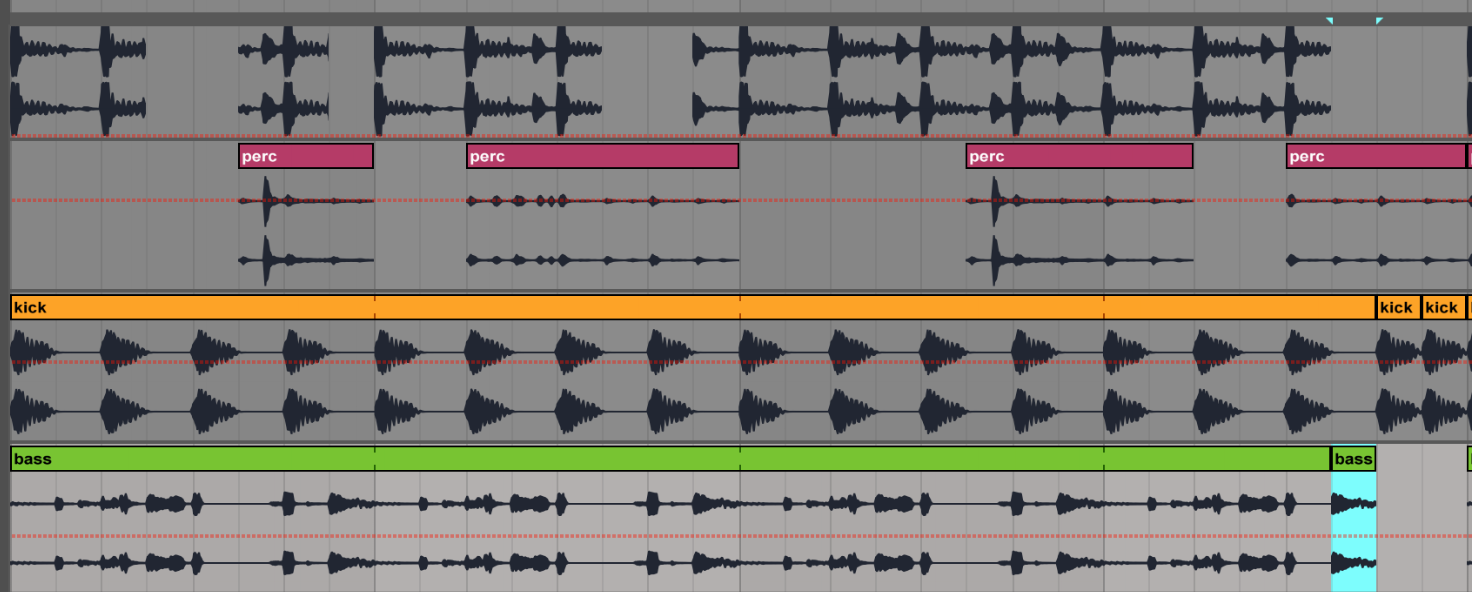

Repetition and counter-rep. In the same vein, when you build the structure of your song, you’ll need to order the sounds in a specific way to give your audio vocabulary some logic, which brings you into a conversation with the listener. Repetition lulls the listener into a comfort zone. It’s where things are smooth, predictable, even hypnotic. Now, in your repetition, it’s fun to play with timing and counter-balance. One sound will appear, then another will reply or echo the first sound, but as an offset element. Usually, the echo can be off and playful, which gives you a lot of room to build layers that add colour and intrigue to your song.

Repetition and counter-rep. In the same vein, when you build the structure of your song, you’ll need to order the sounds in a specific way to give your audio vocabulary some logic, which brings you into a conversation with the listener. Repetition lulls the listener into a comfort zone. It’s where things are smooth, predictable, even hypnotic. Now, in your repetition, it’s fun to play with timing and counter-balance. One sound will appear, then another will reply or echo the first sound, but as an offset element. Usually, the echo can be off and playful, which gives you a lot of room to build layers that add colour and intrigue to your song.

Be wild. This is a favourite of mine. To get the most out of it requires that you get inspiration from other genres that you might not listen to. In my case, I’ve sometimes listened to contemporary classical, weird jazz, or bluegrass to see what and how things are made. Then I try to apply an element or principle into my own music, either pertaining to the structure, percussions, breakdown, or intro. There’s a lot to be learned from other genres.

SEE ALSO : Creating Timeless Music

So with all that being said, within the life cycle of a track, you’ll go through:

So with all that being said, within the life cycle of a track, you’ll go through: So overall, a full day’s work at the studio involves only about 2-3 hours of actual music production. A lot of my time will be spent on tweaking, searching, checking references, checking emails, and taking many breaks that might appear as procrastination.

So overall, a full day’s work at the studio involves only about 2-3 hours of actual music production. A lot of my time will be spent on tweaking, searching, checking references, checking emails, and taking many breaks that might appear as procrastination.