Improving Your Workflow to Prevent Decision Fatigue

What makes on 30-minute block of music making painful versus some other 30-minute block where everything flows organically? The choices you make can make a huge difference in how you use energy. If you use all your energy in the first 30 minutes of a session, you likely faced too many decisions and ran out of gas.

This overwhelming feeling often comes about when you’ve worked on a loop and mess around with arrangements for a moment before getting discouraged. You’re pretty much burning your brain out and then expect a second wind, but that doesn’t happen right away so easily.

What I’ll advocate throughout this post is a reminder of multiple things explained on my blog that push people to dive into music production and thrive in how they make music instead of being stuck. Strategies to facilitate an easier flow of your music-making are fairly easy, too.

Let’s dive right into the 5 different prerequisites to reach a state of flow.

- Risk

- Novelty

- Complexity

- Unpredictability

- Pattern recognition

One of the things that I didn’t list here which is important to focus on is the intention to spend a moment making something you know well. By venturing too deeply into something that is difficult (something that is, however, sometimes necessary for self-education), you’re acquiring some new information and achieving a good state of flow is not possible. Once you’ve learned a new concept/theory by practicing it multiple times, you’ll get good at it.

Hence the importance of making yourself:

- Start a lot of new projects.

- See most of your songs as lessons where you practice. Forget the aim to create masterpieces or to release all of your songs.

- Spike time where you actively rehearse something you love doing.

When I teach music production, I explain to people that I can teach them everything their DAW can do, but then they’d sit in front of their computer with the idea of making a song and they’d be lost. The approach I encourage is to start by creating a strong base and then modulating each new skill into lessons. The idea is to focus on what’s useful to get from A to B in order to go to C and not try to go from A to Z in one shot.

A strong base means that you know some essentials, but beyond that, you know what you enjoy doing and what you seem to do naturally.

Once this is set and clear, we can approach the first take in my list above—taking risks. To know what taking a risk means, you need to be at ease with something. By risk-taking, I mean to try something in a different way. This can’t be really done if you can’t do the thing first. For example, you can’t take beat programming risks if you don’t know the basics of how your sequencer works (well, you can actually, but just diving in, chances are, your beat may come out with too much risk).

What’s a Risk in Music-Making?

Is it trying a new technique? Is it finishing a song? Is it learning a new software?

Let’s classify it as a single question: “What if?” This can and often imply a notion of risk. So let’s say you’re making loops, perhaps you can ask “what if I extend it to a whole minute instead of 2-bar loops?”

If you observe how we live, we often will do something we love doing and that usually is because we’re flowing in it; we don’t think—things just roll. You don’t have to make a lot of choices because you already know what you have to do. Taking a risk is a way of elevating what you’re doing a notch.

It’s a personal affair, and it’s something to be asked once in a while. But this gives rise to a second point which is novelty.

Self-Learning, Novelty & Complexity

Another thing I’ve been advocating for in past articles is the importance to see the majority of your music projects as lessons. A cycle I often notice is:

- Getting interested in a specific sound, aesthetic, idea, genre direction.

- Research and exploration on how to reproduce or imitate it.

- Struggle.

- Acknowledging a new concept.

- Practice and expression.

- Perfect it.

Each time I’m interested in something specific for music, I spend a lot of time trying to acquire the knowledge and techniques behind it. I spend a lot of time on YouTube on several How-tos, read some blogs and forums, and then test what I have. For instance, when I was obsessed with Dub Techno, I was searching a lot about it, which led me to acquire a lot of information about filters, reverb, chorus and delay, but also something I didn’t expect—noise. When you dig for information, you’ll find one thing you didn’t know or may not have been searching for, which is the novelty that is precious. In the state of flow, the exploration, in a context where you already feel comfortable but are on a quest of expanding, feeds you with a lot of creative energy that makes you get lost in what you do. But usually just before this happens, you’ll have a moment of struggle and it’s important to go over it to really get to the plateau of full creative force.

Once you practice and work on really handling a new skill, you’ll perfect what you do more and more. You’ll be more able to express yourself properly and eventually, you’ll want to perfect things. To get back to my example of Dub, I started to learn about delay techniques, tried many delay plugins and started understanding their personality and types. Same for reverbs, where I really got into plates and how they sound. The new trick I learned was about noise and started to get very much into the different types of noise: pink, white, blue, brown and red. Which then led me to get really interested in random generators, LFOs and modulation. Always adding a layer of information, precision and personality was a way to feed myself with novelty and complexity hand in hand. They’d play ping pong together.

Imperfection and Unpredictability

Choice fatigue roots in the quest of perfection. When you have more than two choices, you have a moment of not knowing. This clicked one day as I was reading a silly article that a lot of CEO in Silicon Valley will start the day with simplifying how they’d dress to make the least number of decisions possible. They’d have a work wardrobe of only a few things and they’d pick one without thinking. I find that flow starts with the yes-man attitude, as well as the why not. So it’s enemy would be a no, without trying.

Being in the flow, in a certain way, is almost the straight opposite of searching perfection. That is, you’re in the moment and you’re grasping something real and spontaneous. In a way, that is a form of perfection. When you begin searching for problems and feel doubtful about your work, I usually suspect you’re not in the flow, at all. You’re trapped in your analytical mind, the ones that questions and doubts. That part is really important much later, but I don’t give it too much importance in how to improve your flow.

A good routine for improving flow includes the following music-making tasks:

- Explore, play, improvise.

- Record everything.

- Tweak to improve, not to perfect.

- Consider the future of what was done. Release or not?

I find that I prefer to record 2 or 3 new songs instead of trying to give one a new life by working on it for 10 hours. I could even recycle the best part of a song that’s not working. Making more tracks makes you practice being more spontaneous but also more accurate in what you do, just like a DJ would get better at mixing, transitioning or doing tricks. As you go, your results need less polishing. For years, I left some imperfections in my work as I felt it was part of what made my music unique and human. It received a lot of positive comments and with time, if I listen to my older tracks, there will be things I don’t like, but I don’t know what was left there purposely or should be considered as a problem. That issue is itself, is part of the soul of the song.

As a mixing engineer, I do get in the zone as well. This is why my first mix of the day is crucial for the rest of the day. I usually start with all corrections, and try to do them in one shot, otherwise I start fixing stuff that clients like. I noticed that with time that if it works, don’t change it.

Now, unpredictability is something that feeds all the other ideas I’ve listed above that help to improve flow:

- Taking risks by not knowing what will happen.

- Discover new ideas you maybe have filtered out.

- Making your routine more complex by including new items.

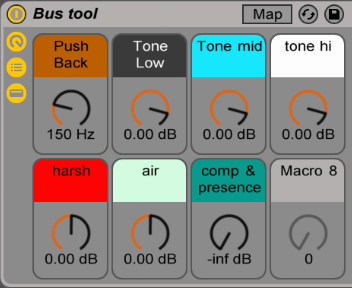

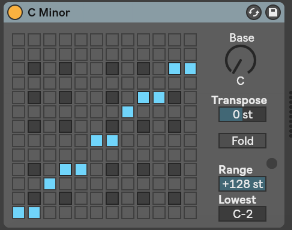

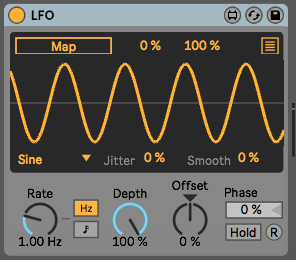

To me, adding a dose of unpredictability starts by making all your elements dynamic with your sounds and effects used. For EQs, I would make sure they’re dynamic (like the Pro-Q3). Compression is dynamic, but I’d link an LFO on the threshold. Adding LFOs, randomizers, and reacting envelopes to the incoming signal would make everything reactive, yet you never are really sure of where it’s going. This is partly explaining how people get addictive to modular synths because it’s all about modulation and unpredictability. A good way to check that is by trying VCV (free) or Softubes’ Modular that is a lot of fun. Reaktor is also an excellent platform to experiment.

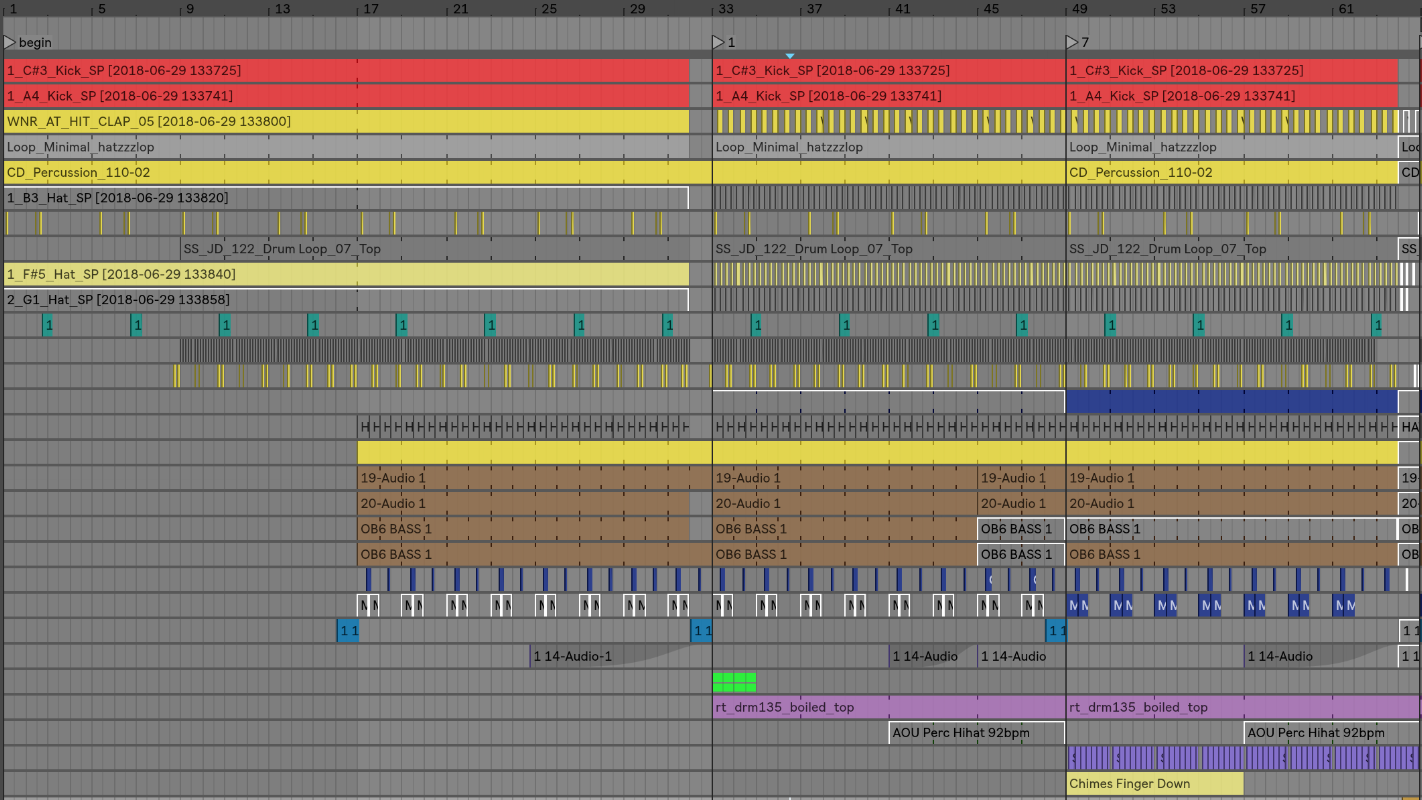

Having separate sessions where you prepare an environment for making music is quite encouraged. By opening Ableton Live and launch a starting template that doesn’t take an hour to setup, you’re allowing yourself to be in the zone. Types of “setup” sessions include:

- Sessions for setting up your future sessions. I’d encourage you to make themes instead of having templates that have all the bells and whistles.

- Record sessions and sound design moments. These will be precious if you want to make music later.

- Tweak, arranging and polishing sessions are helpful, but do them later.

The last aspect of improved workflow I’d like to discuss in more detail is pattern recognition—the moment where you realize that you’ve had a good or bad session, and are able to reconcile what happened in order to prepare the next session.

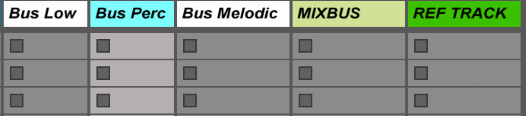

I like to tell my students that if you struggle in a session, it’s mostly because your preparation wasn’t adequate. If you struggle to arrange your session, start small…like, really small. Start from bottom to top: low end, percussion, mids, highs.

If you also fail to finish a jam, maybe you get distracted—a crucial thing to fix. Try to mute all notifications on your phone. Close social media, have snacks and water nearby. Avoid anything that can make your body and mind leave the moment to be elsewhere. If your session lasted at least 20 minutes, you’ve succeeded. Sometimes people feel sessions have to be long, but 20 minutes is sort of the key to get in the zone (unrelated, but this is also why I believe 1 hour DJ sets aren’t fair for the artist).

Personal Rules and Studio Attitude

- Be a yes-man to any idea that comes up until tried in context.

- Avoid maybes. It’s either a hell yes, or no. A maybe is a no, by default.

- Save all rejected ideas for future use.

- If it doesn’t feel good, stop everything. After a pause resume, or change tasks.

- If something feels like a lot of effort, take a pause and come back later.

- If you only have negative points of view, do something else.

- If an inner voice insists that you can’t do this or that (music-wise), I suggest you do it anyway to see what happens. Sometimes we stop ourselves from doing things that are creative.

- Collaborate as much as possible.

- Each session should have a session of listening before or after.

- Stay curious and open!

Let me know your experiences with decision fatigue and improving your own workflow!

First, know your music. Whatever genres you listen to, please get to know what it has and needs. If you read this blog regularly, you know that I always insist on knowing and using references. The mothership method also starts with references. There are a few essential questions you need to ask yourself when you listen to your references:

First, know your music. Whatever genres you listen to, please get to know what it has and needs. If you read this blog regularly, you know that I always insist on knowing and using references. The mothership method also starts with references. There are a few essential questions you need to ask yourself when you listen to your references:

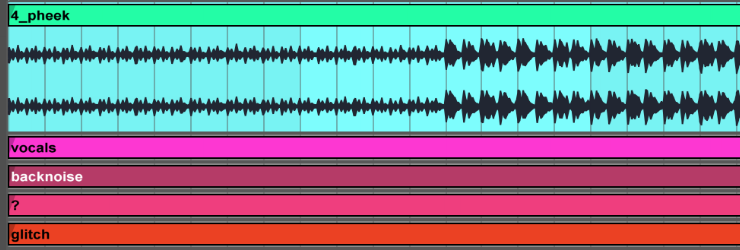

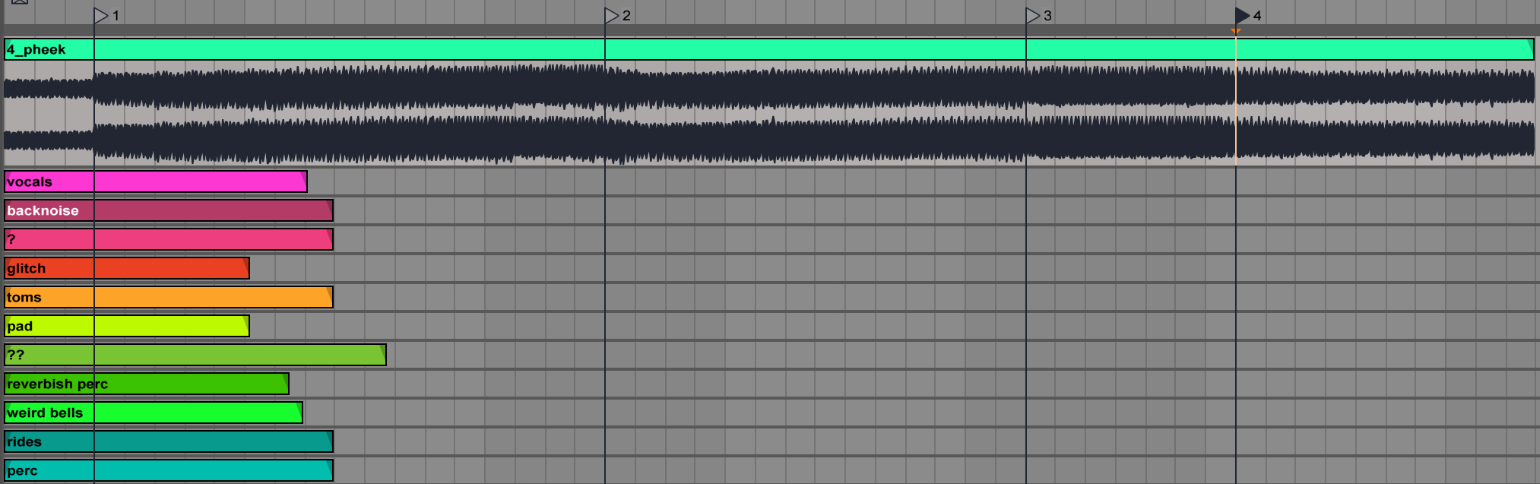

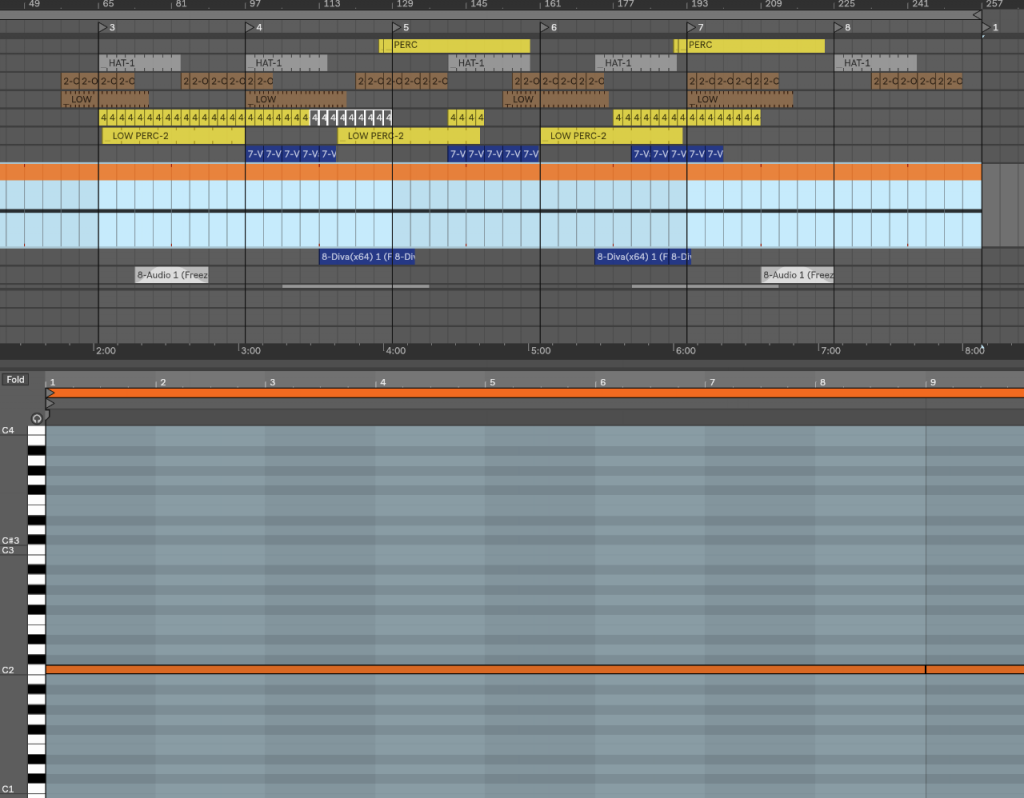

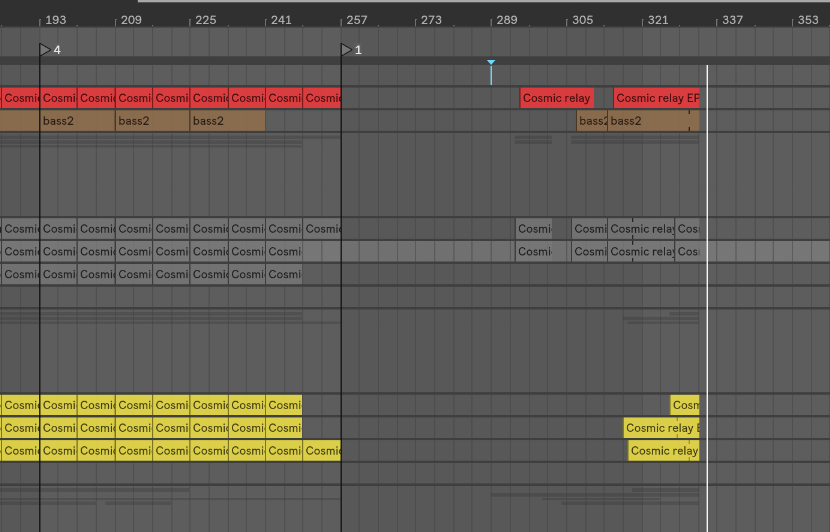

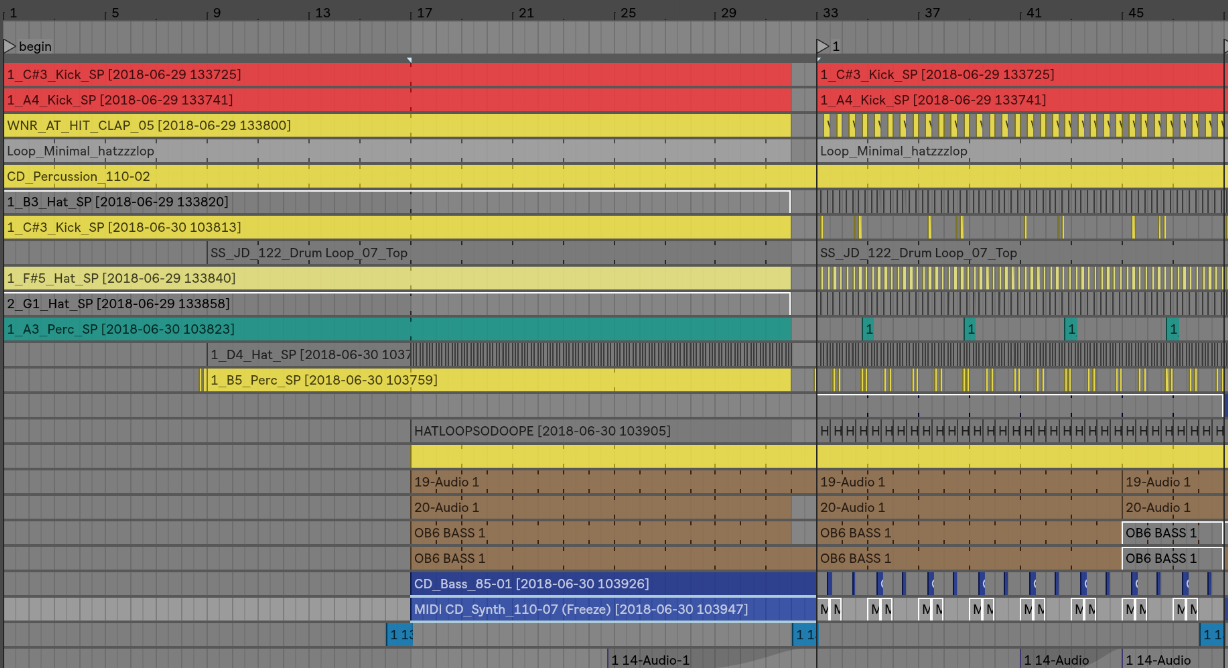

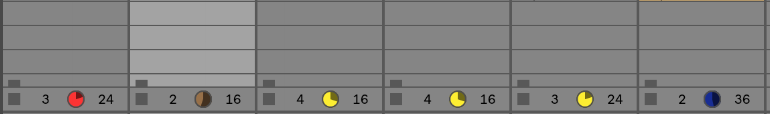

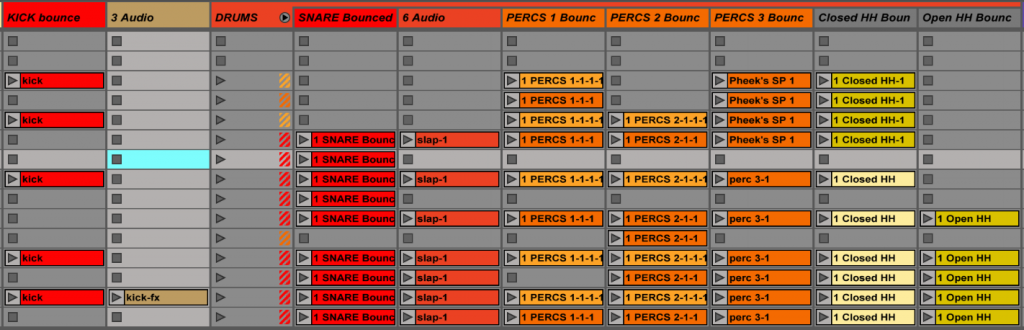

Before consolidation

Before consolidation Clips consolidated

Clips consolidated And duplicated

And duplicated

the organization.

the organization.

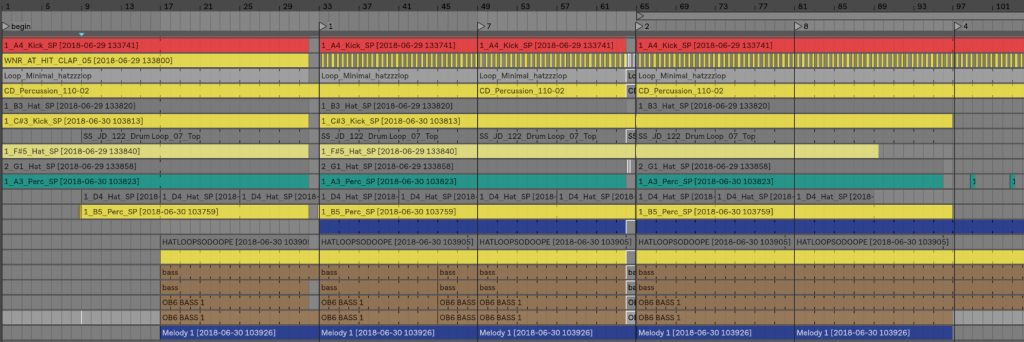

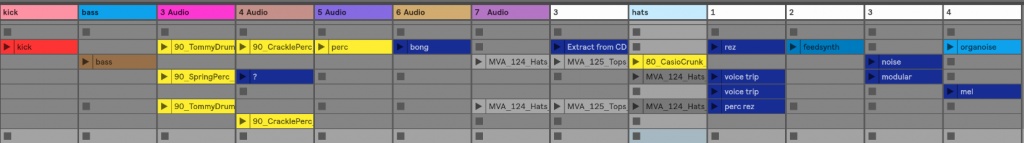

Filtering ideas into a concept

Filtering ideas into a concept basslines. If that’s not enough you can also use the midi effect velocity which can not only alter the velocity of each note, but in Ableton Live it also has a randomizer which can be used to create a humanizing factor. Another way to add dynamics is to use a tremolo effect on a sound and keep it either synchronized, or not. The tremolo effect also affects the volume, and is another way of creating custom made grooves. I also personally like to create very subtle arrangement changes on the volume envelope or gain which keeps the sound always moving.

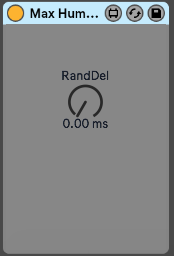

basslines. If that’s not enough you can also use the midi effect velocity which can not only alter the velocity of each note, but in Ableton Live it also has a randomizer which can be used to create a humanizing factor. Another way to add dynamics is to use a tremolo effect on a sound and keep it either synchronized, or not. The tremolo effect also affects the volume, and is another way of creating custom made grooves. I also personally like to create very subtle arrangement changes on the volume envelope or gain which keeps the sound always moving. modulate anything, and they will automatically create movement. For each LFO, I often use another LFO to modulate its speed so that you can get a true feeling of non-redundancy.

modulate anything, and they will automatically create movement. For each LFO, I often use another LFO to modulate its speed so that you can get a true feeling of non-redundancy. A sound’s position in a pattern can change slightly throughout a song to create feelings of movement; a point people often overlook. This effect is easier to create if you convert all of your audio clips to midi. In midi mode you can use humanizer plugins to constantly modify the timing of each note. You can also do that manually if you are a little bit more into detail editing but in the end a humanizer can do the same while also creating some unexpected ideas that could be good. Another trick is to use a stutter effect in parallel mode to throw a few curve balls into the timing of a sound every now and then.

A sound’s position in a pattern can change slightly throughout a song to create feelings of movement; a point people often overlook. This effect is easier to create if you convert all of your audio clips to midi. In midi mode you can use humanizer plugins to constantly modify the timing of each note. You can also do that manually if you are a little bit more into detail editing but in the end a humanizer can do the same while also creating some unexpected ideas that could be good. Another trick is to use a stutter effect in parallel mode to throw a few curve balls into the timing of a sound every now and then.

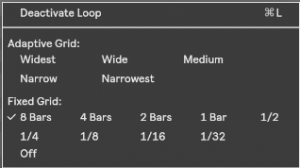

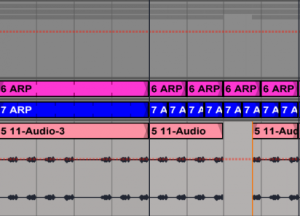

Legato: This is probably the most useful thing to activate for clips in variation. Basically, the Legato option will let the selected clip to take over the one that was previously played, based on the quantization you have set. So for instance, let’s say you play a hihat clip, then press the first clip of the variation. It will stop the activated clip and immediately switch to the other one you just started. On the image, I have set it to 1/16, meaning it will be played on the next 1/16th, keeping it on tempo. Keep in mind that the variation clips are “in sync” with the one playing so that it will continue at the same position in the clip. If legato wasn’t activated, it would start at the beginning of the clip.

Legato: This is probably the most useful thing to activate for clips in variation. Basically, the Legato option will let the selected clip to take over the one that was previously played, based on the quantization you have set. So for instance, let’s say you play a hihat clip, then press the first clip of the variation. It will stop the activated clip and immediately switch to the other one you just started. On the image, I have set it to 1/16, meaning it will be played on the next 1/16th, keeping it on tempo. Keep in mind that the variation clips are “in sync” with the one playing so that it will continue at the same position in the clip. If legato wasn’t activated, it would start at the beginning of the clip. Intensity Variation: If you want to quickly go from open hihat to closed one, one of the fastest way is to play with the “Preserve” section and set it as in this image. Playing with the percentage will let you adjust how much of the end of each sound can be preserved. Having it at 100% is fully open and let’s say 25% is more closed, building tension. So one variation can be set low at first and then the other ones can be more open. If you see the need to boost the energy quickly, then you can go in one of the variation.

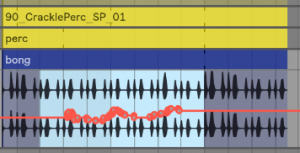

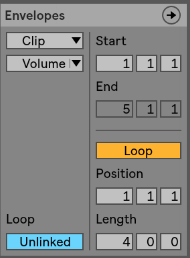

Intensity Variation: If you want to quickly go from open hihat to closed one, one of the fastest way is to play with the “Preserve” section and set it as in this image. Playing with the percentage will let you adjust how much of the end of each sound can be preserved. Having it at 100% is fully open and let’s say 25% is more closed, building tension. So one variation can be set low at first and then the other ones can be more open. If you see the need to boost the energy quickly, then you can go in one of the variation. Envelopes: Super useful for variations as well because you can create automation on a very small scale or a longer one. Many artists will use this on EQ to give life to a clip and making sure it feels like it is alive. The important part is to make sure that the envelope isn’t linked and then you can decide of the length of the automation, on one attribute. Tip: make sure you select “Clip” in the first drop down to make sure the changes are made in the clip itself.

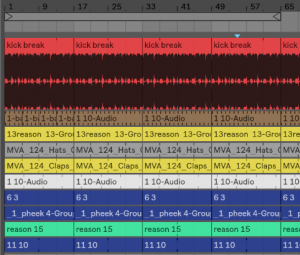

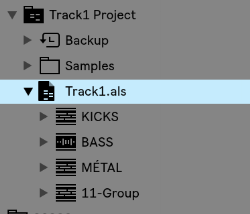

Envelopes: Super useful for variations as well because you can create automation on a very small scale or a longer one. Many artists will use this on EQ to give life to a clip and making sure it feels like it is alive. The important part is to make sure that the envelope isn’t linked and then you can decide of the length of the automation, on one attribute. Tip: make sure you select “Clip” in the first drop down to make sure the changes are made in the clip itself. Next we will import all songs into that project. There are two ways to do this and it’s up to you to decide what is the best for you. I personally like to open a track, grab all clips in the session, copy (cmd+c), then open your “My Live Set” project and paste. You can also copy through the browser and should you be more comfortable using that method, do it that way.

Next we will import all songs into that project. There are two ways to do this and it’s up to you to decide what is the best for you. I personally like to open a track, grab all clips in the session, copy (cmd+c), then open your “My Live Set” project and paste. You can also copy through the browser and should you be more comfortable using that method, do it that way.

I think my best live sets were good mostly because they had a core to work around that had some preparation, but also had a lot of room to improvise, dependent on how the actual event turned out. These sets were versatile; I could open an evening with them or play peak time, mostly because of how flexible they were. These sets were more or less made up of the same songs but the variations would be so easy to perform on the fly that I could really just follow what felt good to me in that moment in time. I’ve never really understood the point of having an overly prepared set. I’ve tried the prepared approach before and it just made the whole experience boring, because there would be no risk-taking; it also felt out of sync with whoever was listening. For example, imagine that your track has been built to have a drop, breakdown at one precise point and a moment of tension after, but if the dance floor is just starting to warm up when you drop, you might lose people’s attention or it might feel out of place.

I think my best live sets were good mostly because they had a core to work around that had some preparation, but also had a lot of room to improvise, dependent on how the actual event turned out. These sets were versatile; I could open an evening with them or play peak time, mostly because of how flexible they were. These sets were more or less made up of the same songs but the variations would be so easy to perform on the fly that I could really just follow what felt good to me in that moment in time. I’ve never really understood the point of having an overly prepared set. I’ve tried the prepared approach before and it just made the whole experience boring, because there would be no risk-taking; it also felt out of sync with whoever was listening. For example, imagine that your track has been built to have a drop, breakdown at one precise point and a moment of tension after, but if the dance floor is just starting to warm up when you drop, you might lose people’s attention or it might feel out of place. Set two variations of the hook with some complementary percussion. If you listen to a DJ set, especially techno or loop based music, you’ll see that it’s mainly a loop with variations. Try to have variations in your percussion, melody or bass. That way you can toggle between the hook and this part. I really really encourage you to listen to DJ sets to get ideas.

Set two variations of the hook with some complementary percussion. If you listen to a DJ set, especially techno or loop based music, you’ll see that it’s mainly a loop with variations. Try to have variations in your percussion, melody or bass. That way you can toggle between the hook and this part. I really really encourage you to listen to DJ sets to get ideas.