8 common mixing mistakes and audio production errors

Since starting my label, and after years of dealing with large numbers of demo submissions and artists, I’ve noticed that most of the time new producers and musicians make the same kinds of errors when they are early in their audio producing years. When I started my studio full-time I also noticed that I have – for the most part – been dealing with the same questions and frustrations about producing audio on a regular basis. This post outlines a list of some of the most common mixing mistakes and general mistakes musicians make when they are starting out.

the most common mistakes I see from Musicians with regards to audio mixing and producing:

Not investing in good monitoring (speakers, headphones).

This one is a huge deal. You’re dependent on what you hear to get quality results. This is always a bit puzzling to me, that some people hope to compete with artists who have invested so much into a professional studio with poor monitoring. If you can’t hear what you do, it’s pretty much like working blindly and the results on good sound systems will be catastrophic. So many people go test music in their car to see if it’s done properly which is sort of ok, but not productive.

What I’d suggest is to try to spend an afternoon listening to music you know on different speakers. Do not invest in cheap monitors because it’s all you can afford. It will fill your music with many problems down the road. Trust your ears.

A Lack of references

You can’t produce quality music if you haven’t been exposed to quality music. This means you need to have in your possession a large library of music for listening, but also to spend just as much time listening to music as producing it. The more you immerse yourself in music that sounds great, the more familiar your ears become with regards to how things should sound. This can mean listening to good quality vinyl or wav files.

What I’d suggest is to have regular sessions of listening music you like attentively and also in the background. Both are important. Make a playlist on Spotify or on your computer of music you know sounds right and train your ears to know that music inside out.

Making Comparisons to Professional musicians too often

This is the downside of referencing as it can play tricks on you. I know some people who have amazingly good tastes in music and want to start producing but when they start and see the work that is ahead, they become frustrated quickly. If you compare yourself to a guy who has been around for 20 years, chances are, you’re setting yourself for defeat.

What I suggest is to focus more on the experience of making music than the result, at first.

Thinking making music is easy

Can’t blame anyone besides the general culture that has been saying for years that “making electronic music” is all about “pushing a few buttons”. People see a DJ with fists in the air and they think “I could do that…”.This mindset will give you a rude awakening when you start working in a DAW and dive into sound design. Electronic music doesn’t require the same skills as playing piano, but will be demanding in terms of technical details. There are so many possibilities that you can go crazy trying to know where to start. Sadly, many people realize that and become depressed.

What I’d suggest before diving in music production is to try to befriend a producer and spend time in studio to see if you really enjoy it. Watch videos on music making to see if you can pick it up quickly too.

Investing too much, too fast

Investing too much, too fast

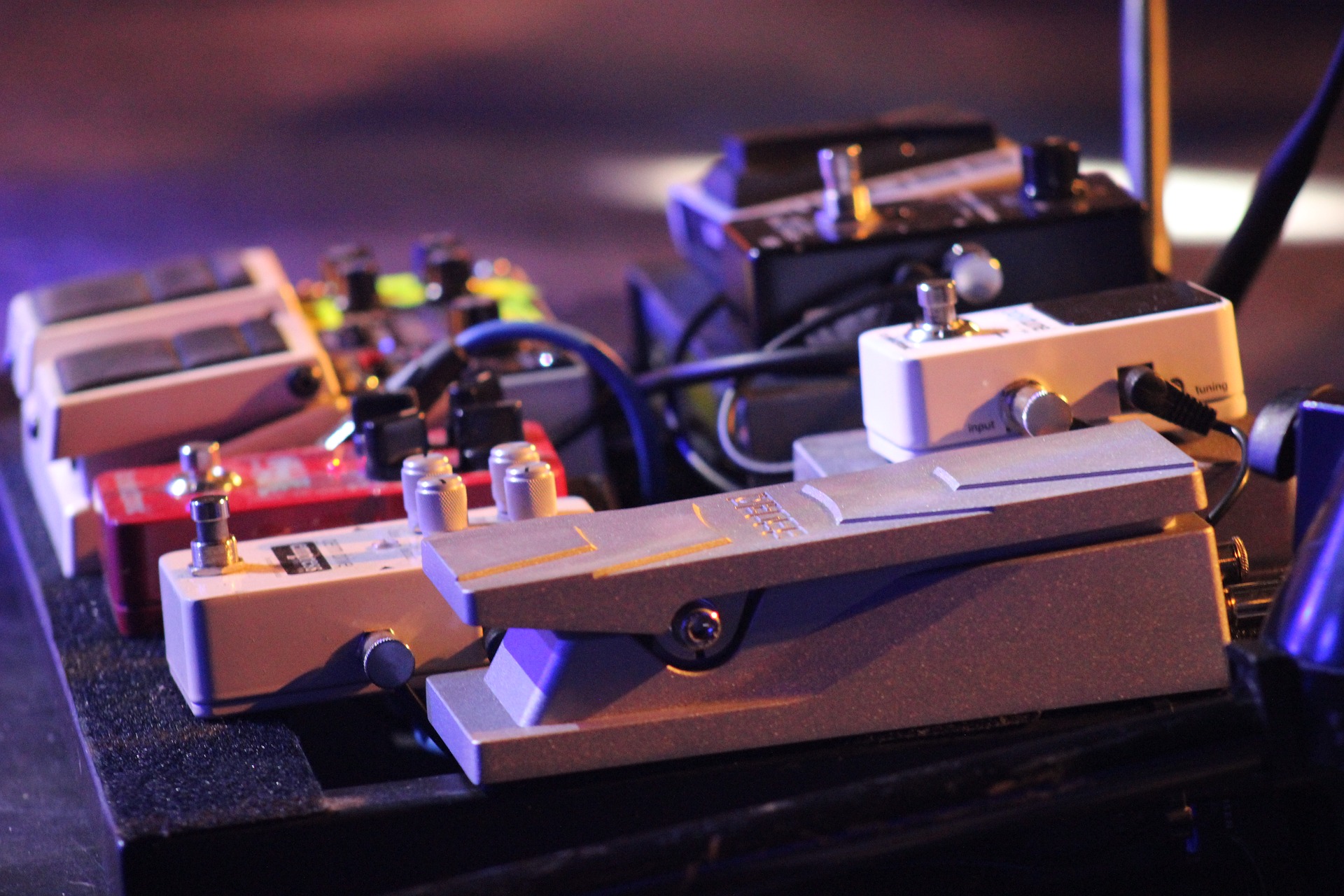

I’m thinking of the guy who decides one day to make music and then comes back home with 5000$ of equipment without knowing if he likes it or knowing what he needs. See what you like doing first, then invest around that. Music production has so many different dimensions that it’s important to know your cup of tea. Is it DJing? Playing synths? Sound design? Making loops? There are pieces of gear you need first as I explained in a previous post but you surely don’t need everything your friends will tell you to buy.

What I suggest was written in a past blog post about what you really need to get started. I often get asked what you need to start making music: a laptop and headphones is all you need at first. Build around that.

CHASING “success” before Building up skills

This is a classic. Knowing what you like is one thing, knowing what you do best is another. We all have certain skills that feel natural and sometimes you need to explore to discover all of them. Planning your DJ career without having done a few gigs and releases is getting a bit ahead of yourself. Take your time; enjoy the fun of making music and success might come down the road. Chasing success can be like pursuing a mirage.

What I suggest would be to really focus on loving making music before anything else. I often encourage people to start with things little such as making music for friends or to share with local DJs. If you build a network of 5-10 people, that’s enough to slowly build your self-trust and eventually emerge at the right time.

A Lack of patience

Making quality sounds and music is like brewing wine/beer: it demands time, patience and some sort of personal isolation for a while. It’s important to stop yourself from sharing your work to the whole world before it is really done. The name of the game in music production is patience and it is the same for anyone who want to go to another level.

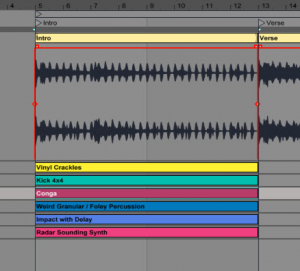

Misguided Audio Production Techniques

If we’re talking tech, this list of issues are some things I always find in the work of new producers. Perhaps you can start changing your techniques if you recognize yourself in this list.

- A lack of quality samples.

- Not using EQs/compression. This one always surprise me.

- Using too many instances of an effect instead of using the Sends/AUX.

- Not using at least one, very good quality EQ or compressor. They really make a difference.

- Not using channel strips in the DAW.

- No mono for the bass or anything under 130hz.

- Not using swing/grooves.

- Missing the boat with saturation. Either it’s not done at all or with tools that aren’t doing the job. Get this free one to get yourself with a good starter kit.

- Lack of post-production on sounds. Whenever you think you’re done with a song, you just realize there’s a number of details you overlooked. The road often feels endless… because it is.

- Muting the kick too often in a track. This kills the energy, especially if you have long breaks with no kick.

- Not letting things go. Sometimes, a simple idea can carry a track for a while but you’ll need to let sink in people’s mind so to do that, you need to trust what you do and let it go. Too often, newcomers are concerned that the listener will be bored and they keep adding or changing things.

You can also ask for help and I will update this list with pleasure!

SEE ALSO : Sound design: create the sounds you imagine inside your head

The path doesn’t need to be cleared from obstacles. Obstacles are the path. (Buddhist Proverb)

The path doesn’t need to be cleared from obstacles. Obstacles are the path. (Buddhist Proverb) It’s given that there are many reasons why a listener might be engaged with your song – the quality of the mix, a

It’s given that there are many reasons why a listener might be engaged with your song – the quality of the mix, a Going back to the article

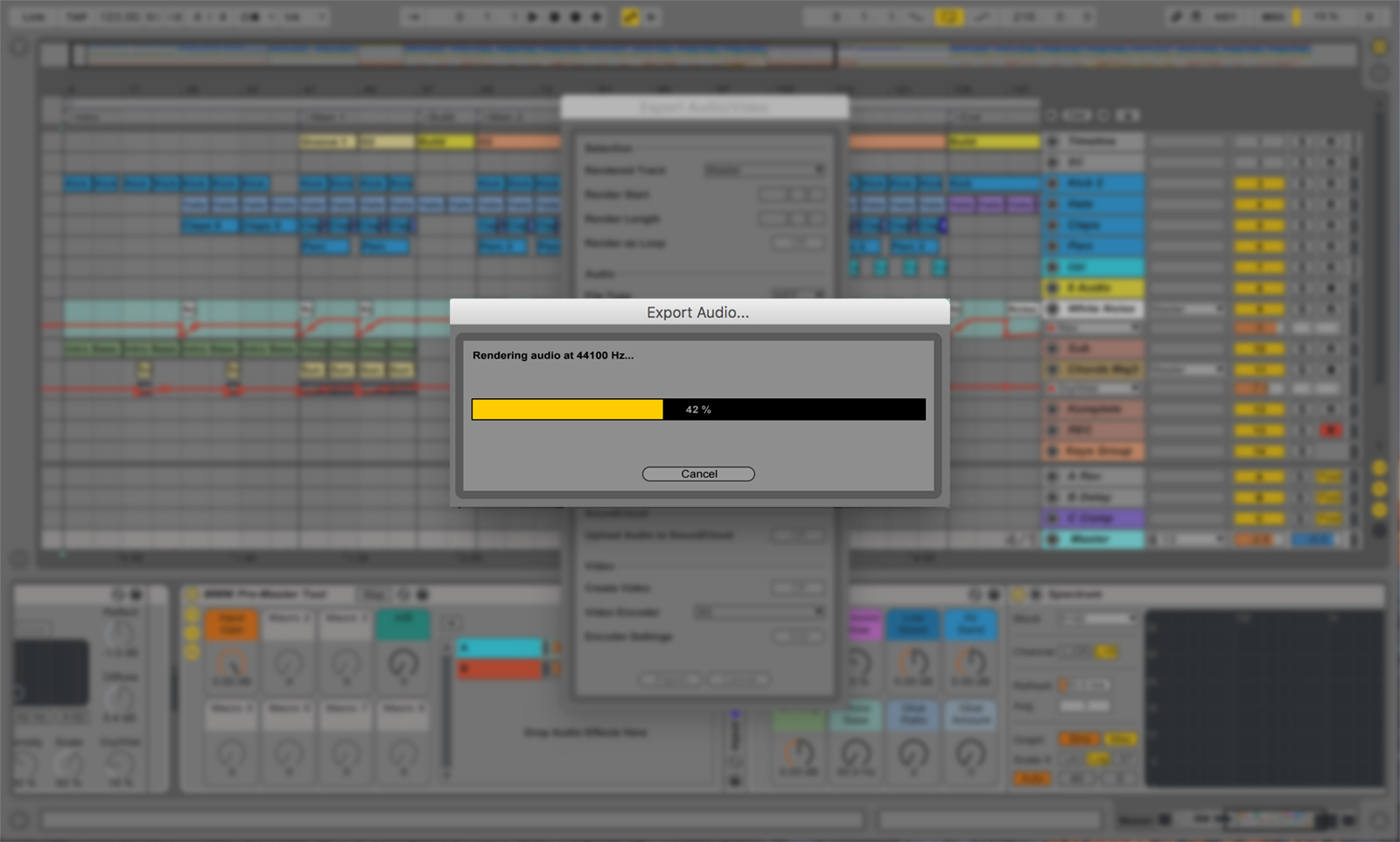

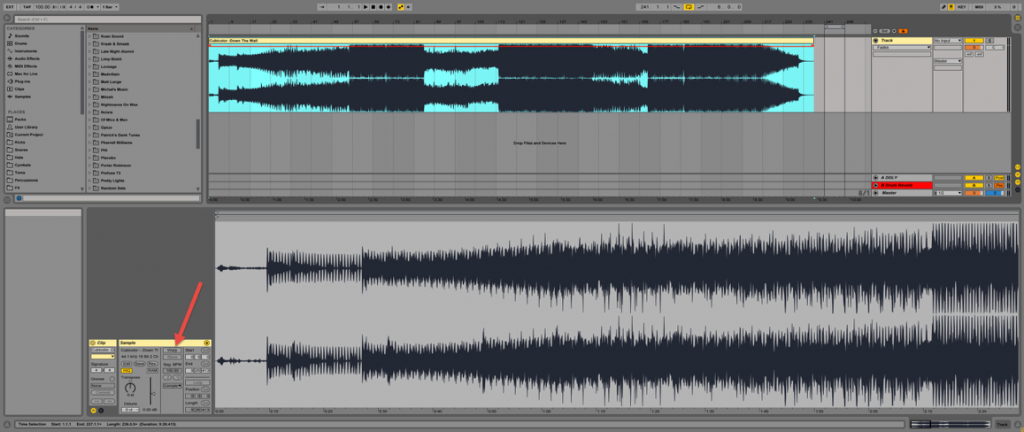

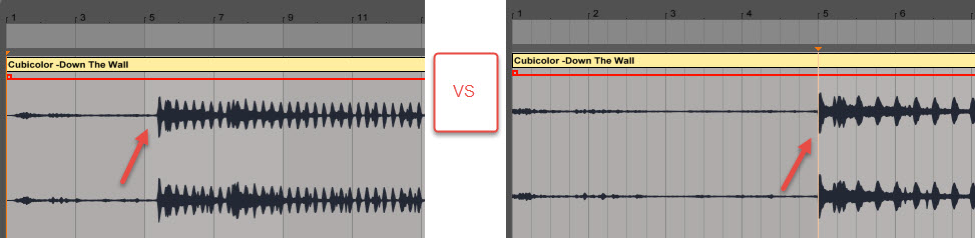

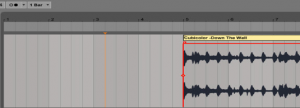

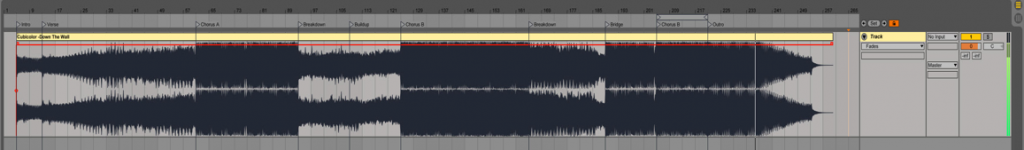

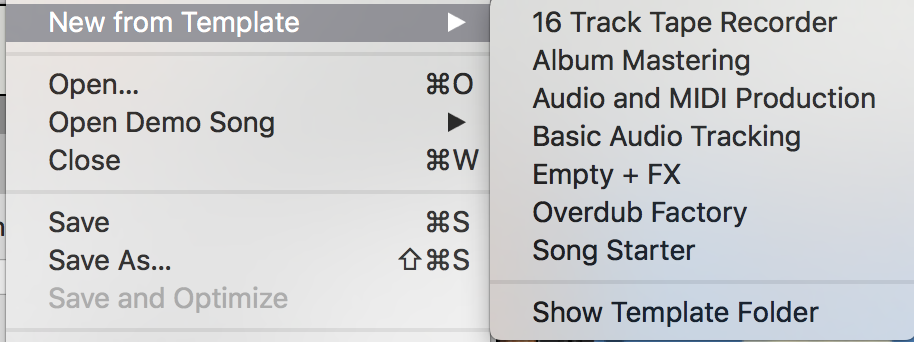

Going back to the article Many DAWs can be setup to load a template as an initial starting point. Reason will propose a pre-made environment, and Studio One will propose if you’d like to setup a project for mixing to speed up your getting started time. Ableton Live doesn’t have that feature by default, but you can easily change that to open a custom startup project.

Many DAWs can be setup to load a template as an initial starting point. Reason will propose a pre-made environment, and Studio One will propose if you’d like to setup a project for mixing to speed up your getting started time. Ableton Live doesn’t have that feature by default, but you can easily change that to open a custom startup project.