The Science Behind Tracky Music

I will always remember that day in 1989 when I went to the local record shop after school to see if they had received some rare techno records that had just been released. There were about 5 of us in town who were eager to get our hands on them, and it was a race to who would grab them first. This might sound surreal to you if you’re younger, but those were the days when each record you bought was precious. You’d often even buy the ones you were unsure of in case you liked it later… or because you didn’t want other DJs to have it. Funny, eh? We were at the opposite edge from our current times with music accessibility.

So that day, I was listening to records in the “Techno – Fresh Arrivals” section of the shop. There were these 3 odd-looking ones (I still have them) with no information on them but colours. The green one had the same loop playing all the way through, from beginning to end. There were basically no variations, from what I could tell. “This is really weird!” I thought. I didn’t get the purpose of it. Then I listened to the second record — same concept, different colour. Last record, same thing. Puzzled, something inside of me pushed me to buy them. There was something about those records I just couldn’t pass up.

So that day, I was listening to records in the “Techno – Fresh Arrivals” section of the shop. There were these 3 odd-looking ones (I still have them) with no information on them but colours. The green one had the same loop playing all the way through, from beginning to end. There were basically no variations, from what I could tell. “This is really weird!” I thought. I didn’t get the purpose of it. Then I listened to the second record — same concept, different colour. Last record, same thing. Puzzled, something inside of me pushed me to buy them. There was something about those records I just couldn’t pass up.

That was the first time I bought tracky records. 1989

I got to a friend’s place and we started to mix them, and suddenly it all started to make sense. The music was always changing, but very subtly. The records were mind-boggling, and I fell in love with them. We discovered we didn’t need songs — we had the tools to build our own stories. It was exhilarating.

Tracky music was a revelation. It taught us that no music is boring if correctly used, and that techno is not necessarily made to be listened to as is, but used as raw material.

Tracky music was a revelation. It taught us that no music is boring if correctly used, and that techno is not necessarily made to be listened to as is, but used as raw material.

See, the thing about tracky records is that they’re used with others in order to create something completely new. Have you ever heard of 1 + 1 = 3? One record, mixed with another, makes 3 different layers (the 3rd layer is created by combining the other 2).

Making tracky music poses some challenges and the number one is, how to not be boring with simplistic elements.

There are some basic rules for making tracky music, but the great news is that breaking them is where the fun really starts.

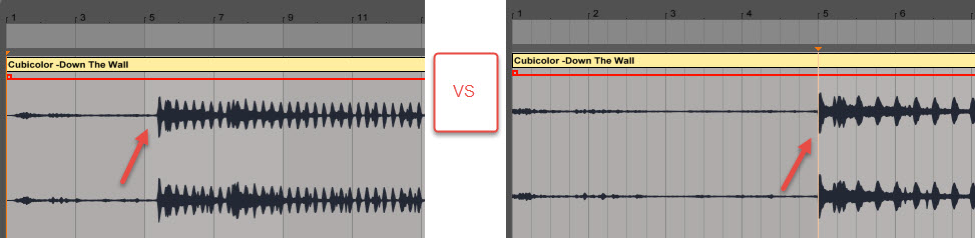

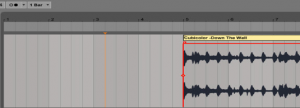

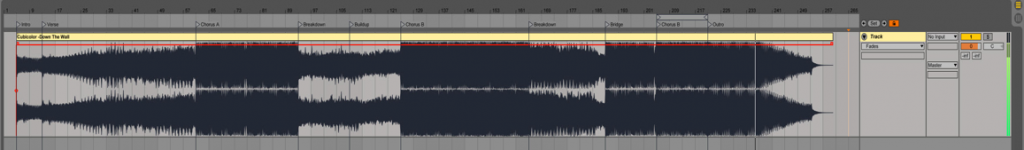

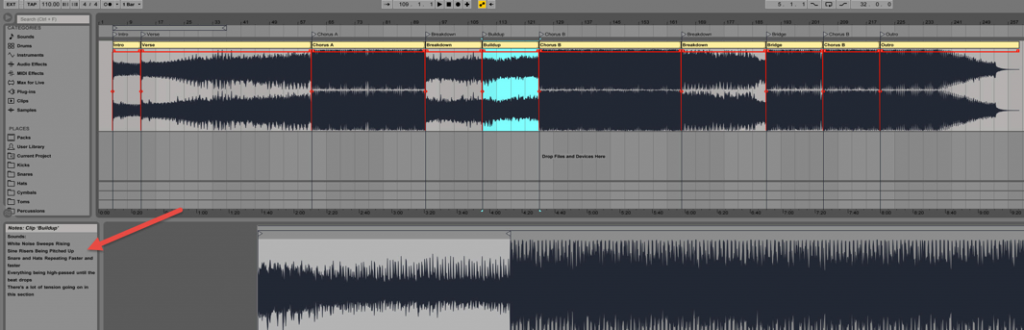

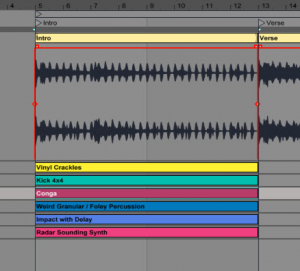

- Organized for DJs. The more organized your track is, the easier it will be to mix. This is why it’s important to place redundant elements in multiples of 4. Very useful.

- Micro vs macro repetition. Start by the smallest loop possible, and then expand it. You can start by the smallest, simplest kick-hats-snare combo, for example, and then start adding a sound looped on a longer scale to make the small loop feel scaleable. The careful addition, spread over time, will allow the listener to process it and make the repetition feel more palatable. But it’s not about making music for listening, it’s about making music as raw material for someone else.

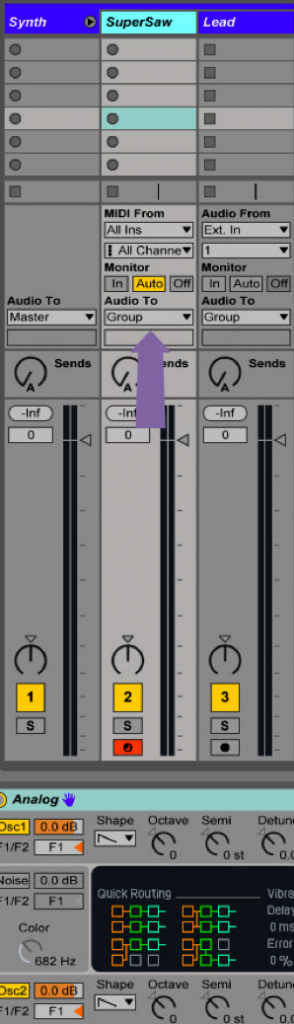

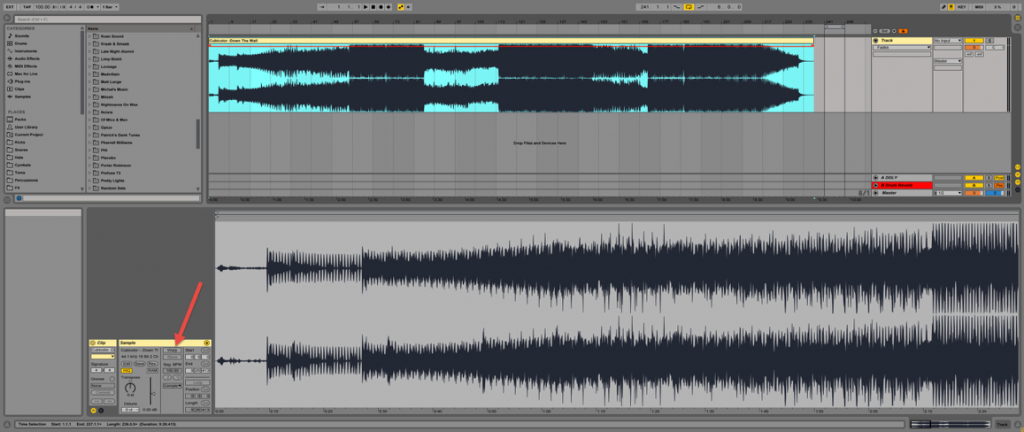

- Subtle variations. Try making automations that last over 1 minute or longer. This will create the subtle impression that something is going on, but since the changes are happening so slowly, it will be super hard to pinpoint exactly what. Some things you can automate: EQ gain, filtering, panning, volume gain, effect wet/dry.

- Arrangement surprises. Mix a number of predictable arrangements with more destabilizing ones. For instance, you can throw a clap in every 3 bars so the listener will come to expect it, and then later remove one clap to throw them off, before finally bringing it back in.

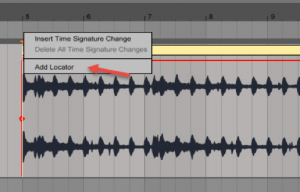

- Develop your vocabulary. This is a huge topic in itself. For now though, you need to know that 1 bar of tracky music may have its own vocabulary, and that it’s important to be consistent about it. So every 32 bars, for example, you could insert a little silence to accentuate the transition. If you mute something, you are muting a part of a sentence. This will be explored in greater detail in a future post…

Here are some great artists whose tracks you can use as references: Mountain People, Gez Varley, Barac, Mike Ink.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZQjrOHMygZ0

Enjoy!

SEE ALSO : Self-Imposed Rules For Arrangements