Electronic Music Coaching Lessons

There is this attitude in electronic music that if you share your secrets and techniques that somehow an essence of it will get lost, and some of the magic will dissipate. Additionally, people may take that advice, utilize it, and somehow outgrow and surpass the teacher. And nobody wants to feel like they dug their own grave. This philosophy about electronic music coaching took me some time to overcome, and I’m glad I did.

Instead of the relationship between teacher and student becoming parasitic, instead I have found it to be purely symbiotic. Sure, some students have surpassed me in many aspects, but I find that they are reciprocal about their newfound knowledge. Now I have many people who are happy to help me with aspects of music making that I don’t enjoy doing as much as they do.

George Martin helping The Beatles. He would have been excellent at electronic music coaching.

Success Takes A Team

As I’ve harped on in previous posts, it makes sense to delegate some of the tasks of your music making, as this is what happens in every other genre of music, yet, for some reason, seems to be stigmatized in electronic music. Think about it, The Beatles had George Martin, Miles Davis had Herbie Hancock. Michael Jackson had Quincy Jones (as did Frank Sinatra). It doesn’t make you less of a musician to be the teacher and embolden your students; it empowers you and propels you to greatness.

That’s why, around Spring of 2016, I announced on my Facebook page that I’d do free electronic music coaching to anyone who would come to me. Back then, it was just a pure invitation to share my knowledge to people and using Mailchimp’s newsletter technology, I was hoping I could send emails to people and guide them in exercises.

Initial Experiments In Electronic Music Coaching And The Lessons Learned

My initial attempt kinda failed pretty quickly as my lack of understanding of the email technology drove some of the participants mad and I had more damage control to do than coaching. So I closed that option and decided to open an electronic music collective / Facebook group with a precise goal – to provide a safe space for anyone who was unsure about their music before posting it publicly or sending it to a label. Of course, any question would be welcomed and we would have a hive mind to answer questions from various people.

As I’m approaching 5 years of free electronic music coaching, I’ve learned a lot from this. From giving feedback and to seeing mentees grow into solid musicians, these are the scenarios I saw play out.

Common scenarios In Electronic Music Coaching

Pretty much everyone who came to me to get some help had one thing that was blocking them from something. A minority would come to perfect their skills and some would come to have guidance in different situations but in the most part, people come to me because they’re blocked. In our electronic music collective, the more specific questions are usually searching for a specific effect used to replicate a sound or getting feedback on a song. These are quickly answered by the community that share a few ideas and hints. Often, it might not be exactly what the person needs but it often guides them down a path that may lead them to something more proactive.

However when doing one-on-one electronic music coaching, I often am presented with the same problems:

- People who are experiencing a major writer’s block and are feeling helpless.

- Aspiring artists that have worked really hard and are feeling stuck, not seeing improvements.

- People who have the loopy syndrome, having countless loops but not being able to finish songs.

- People who have deep love for what they create and are stubborn about any criticism, or conversely, they have intense hate towards what they create, and beat themselves up over it.

How Evolution Impacts Knowledge

If you look in hindsight at what happened in the world of electronic music production in the last 20 years, the software world paired with the internet has made it much simpler. 20 years ago, we were limited to a few resources and we’d always be in stasis waiting for our answers to come (if they ever did). We are now living in a world where we are constantly having our attention pulled in multiple directions, with each direction espousing that “this is the true way,” when there is rarely a “true way” for anything, especially in art.

It’s these conflicting statements that seeds a ton of doubt, or unnecessary confidence in their practitioners. This doubt, or this overconfidence that my one on one sessions seek to remedy.

There is nothing wrong with being confident in your work, but overconfidence creates barriers to learning, and conflicts with progress. Sometimes I wonder why these people want electronic music coaching at all, but the fact that they get it, shows they at least have a conscious understanding of its importance, even if their subconscious confidence conflicts with it.

Conversely, the doubt that many musicians have creates a similar problem. They may be in coaching to become more confident, but their lack of confidence results in that sort of barking little dog syndrome, where any bit of critique damages their already delicate creative ego, even if they consciously know it’s necessary. This can be likened to something like physical therapy; it’s going to hurt to walk again if you broke both your legs, and you’re going to hate it, but you know it’s necessary.

Successful Students

After coaching for over 15 years total, I had noticed that some people did better than others. At the beginning, I was working with a plan, and would teach all the people the same things but I quickly adapted that because it was not working well. Some were learning fast and would provide some interesting challenges or questions while others had some of the same questions but were always struggling on basic issues.

I understood one thing which is, you can’t really teach electronic music theory and music production training from a rigid approach because what makes it successful is to understand someone globally and then, as a team, find strategies to build a routine and work habits. More importantly, I tried to help the person find its own way of learning through the internet jungle.

Here are common points that people who succeeded had:

- They had a clear direction: People that I see with a clear intention and direction, such as “wanting to sound like X”, are the easiest to guide. If you have a target and goal, you can always try to push what you do and technically study how it is done with music you have on hand. With my help, we can reverse engineer some songs and try different things. Once that target is mostly reached, what’s interesting is how it leads them elsewhere. The fact that they know how something is done allows them to discover other artists or songs that are itching their curiosity. But working with targets, is always a clear indication of improvement.

- They showed consistency: Anyone who works on a regular basis, over a constant time, has shown great improvement. More than people who started really strong but couldn’t keep up the pace. Working hard isn’t always smart. It’s more about knowing what you can do and try to consistently learn something new, practice it and then putting it into context of a song.

- They asked a lot of questions: Often creative success and inquisitivity go hand in hand. Asking for advice and technical guidance is a must if you wish to go far. You can do everything yourself but you’re not giving yourself the chance to grow adequately. Even if someone thinks otherwise than you, there’s some part of his view that can be useful.

- They stayed humble and always wanted to learn. If you come with the idea that you’ll learn something everyday, you won’t be stagnant in whatever you do and will always be looking forward.

- They were not afraid of rejection and criticism. Because each song is an experiment in itself and anyone’s point of view is arbitrary.

Struggling points

These are individuals who have been facing a number of problems in the learning and while have learned a lot and improved much, they unfortunately haven’t rolled out as much as they wished. These are what commonly hinder them.

- The student focuses on the success of a specific song.

- They work in a linear fashion and won’t change.

- Insisting on doing everything themselves.

- The musician is often convinced they know more than they do.

- Their expectations are set really high.

- The belief that hard work brings success is deeply ingrained in them.

- They see music in a hierarchical way.

What I’ve Learned In Electronic Music Coaching

The Latin proverb docendo discimus translates to “by teaching, we learn.” These are some of the lessons I’ve learned by teaching others.

Free isn’t always a good thing

If you give something for free, it doesn’t always have value. Free advice is cheap advice. Unless people pay for it, there is less of a chance that they will anchor said advice. Not saying that giving free advice is bad; that’s what these blog posts and the group flourishes on. It’s just that they can be easily dismissed. However, if you paid for advice, there is a greater chance that you implement it.

Consistency is key to development

Think of it like training for a sport. If you are training for a marathon, and decide to take a month off, you’re going to have to spend time ramping back up to that level. Additionally, the longer you put something off, the more chance you have to disregard it.

Not be afraid of making mistakes

The comic strip artist Scott Adams has a really poignant quote about mistakes in the creative journey. He says, “Creativity is allowing yourself to make mistakes. Art is knowing which ones to keep.” I find this statement to be very true. Many of my favorite parts of my works have come unintentionally, or are a result of seriously messing something up.

Being part of the community

No man is an island. Civilization was built by teams, and communities, not individuals. Teaching has allowed me to be part of a vibrant community, and for that I am extremely grateful. It has taught me at least as much, and provided me as many resources, as I have provided others.

Other Benefits of Electronic Music Coaching

Since my music is pretty esoteric, I learned over decades of performing that the people who attended my shows were cut from a similar cloth. They were musicians, and sound designers, eager to absorb some of the essence of the performance in order to translate it into their own creations.

This gave me the realization that in order to grow and keep my fan base engaged, I had to give the people what they wanted. Therefore, electronic coaching became not only empowering creatively, it became a solid marketing channel.

If you’re interested in becoming part of our community and getting some free coaching, join our electronic music collective, Pheek’s Coaching Corner. We also have a bunch of tutorials on YouTube as well. If you want more personalized coaching, I offer that as well.

One of the most revered electronic albums of the last decade is Jon Hopkins’ blistering techno/neo-classical masterpiece,

One of the most revered electronic albums of the last decade is Jon Hopkins’ blistering techno/neo-classical masterpiece,

Filtering ideas into a concept

Filtering ideas into a concept

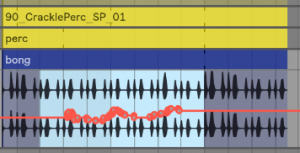

Legato: This is probably the most useful thing to activate for clips in variation. Basically, the Legato option will let the selected clip to take over the one that was previously played, based on the quantization you have set. So for instance, let’s say you play a hihat clip, then press the first clip of the variation. It will stop the activated clip and immediately switch to the other one you just started. On the image, I have set it to 1/16, meaning it will be played on the next 1/16th, keeping it on tempo. Keep in mind that the variation clips are “in sync” with the one playing so that it will continue at the same position in the clip. If legato wasn’t activated, it would start at the beginning of the clip.

Legato: This is probably the most useful thing to activate for clips in variation. Basically, the Legato option will let the selected clip to take over the one that was previously played, based on the quantization you have set. So for instance, let’s say you play a hihat clip, then press the first clip of the variation. It will stop the activated clip and immediately switch to the other one you just started. On the image, I have set it to 1/16, meaning it will be played on the next 1/16th, keeping it on tempo. Keep in mind that the variation clips are “in sync” with the one playing so that it will continue at the same position in the clip. If legato wasn’t activated, it would start at the beginning of the clip. Intensity Variation: If you want to quickly go from open hihat to closed one, one of the fastest way is to play with the “Preserve” section and set it as in this image. Playing with the percentage will let you adjust how much of the end of each sound can be preserved. Having it at 100% is fully open and let’s say 25% is more closed, building tension. So one variation can be set low at first and then the other ones can be more open. If you see the need to boost the energy quickly, then you can go in one of the variation.

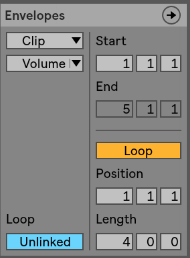

Intensity Variation: If you want to quickly go from open hihat to closed one, one of the fastest way is to play with the “Preserve” section and set it as in this image. Playing with the percentage will let you adjust how much of the end of each sound can be preserved. Having it at 100% is fully open and let’s say 25% is more closed, building tension. So one variation can be set low at first and then the other ones can be more open. If you see the need to boost the energy quickly, then you can go in one of the variation. Envelopes: Super useful for variations as well because you can create automation on a very small scale or a longer one. Many artists will use this on EQ to give life to a clip and making sure it feels like it is alive. The important part is to make sure that the envelope isn’t linked and then you can decide of the length of the automation, on one attribute. Tip: make sure you select “Clip” in the first drop down to make sure the changes are made in the clip itself.

Envelopes: Super useful for variations as well because you can create automation on a very small scale or a longer one. Many artists will use this on EQ to give life to a clip and making sure it feels like it is alive. The important part is to make sure that the envelope isn’t linked and then you can decide of the length of the automation, on one attribute. Tip: make sure you select “Clip” in the first drop down to make sure the changes are made in the clip itself. 1. The Hook

1. The Hook 2. Sound design

2. Sound design 5. Structure/Arrangements

5. Structure/Arrangements

I think my best live sets were good mostly because they had a core to work around that had some preparation, but also had a lot of room to improvise, dependent on how the actual event turned out. These sets were versatile; I could open an evening with them or play peak time, mostly because of how flexible they were. These sets were more or less made up of the same songs but the variations would be so easy to perform on the fly that I could really just follow what felt good to me in that moment in time. I’ve never really understood the point of having an overly prepared set. I’ve tried the prepared approach before and it just made the whole experience boring, because there would be no risk-taking; it also felt out of sync with whoever was listening. For example, imagine that your track has been built to have a drop, breakdown at one precise point and a moment of tension after, but if the dance floor is just starting to warm up when you drop, you might lose people’s attention or it might feel out of place.

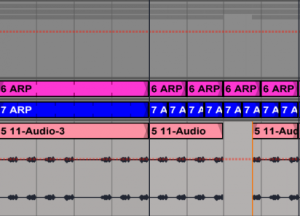

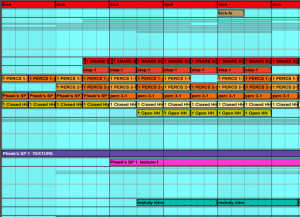

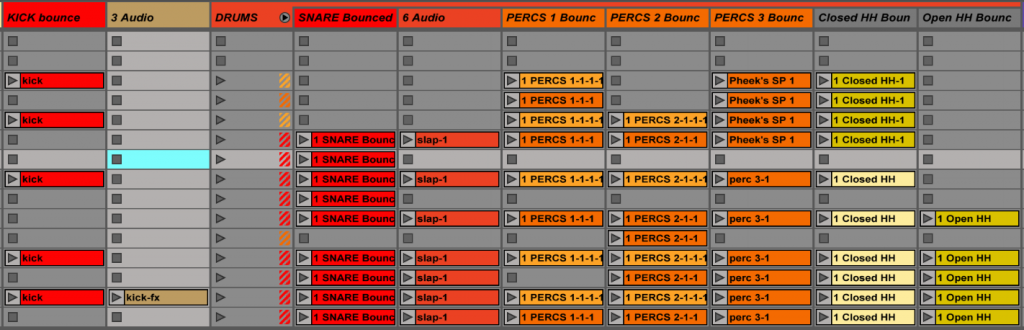

I think my best live sets were good mostly because they had a core to work around that had some preparation, but also had a lot of room to improvise, dependent on how the actual event turned out. These sets were versatile; I could open an evening with them or play peak time, mostly because of how flexible they were. These sets were more or less made up of the same songs but the variations would be so easy to perform on the fly that I could really just follow what felt good to me in that moment in time. I’ve never really understood the point of having an overly prepared set. I’ve tried the prepared approach before and it just made the whole experience boring, because there would be no risk-taking; it also felt out of sync with whoever was listening. For example, imagine that your track has been built to have a drop, breakdown at one precise point and a moment of tension after, but if the dance floor is just starting to warm up when you drop, you might lose people’s attention or it might feel out of place. Set two variations of the hook with some complementary percussion. If you listen to a DJ set, especially techno or loop based music, you’ll see that it’s mainly a loop with variations. Try to have variations in your percussion, melody or bass. That way you can toggle between the hook and this part. I really really encourage you to listen to DJ sets to get ideas.

Set two variations of the hook with some complementary percussion. If you listen to a DJ set, especially techno or loop based music, you’ll see that it’s mainly a loop with variations. Try to have variations in your percussion, melody or bass. That way you can toggle between the hook and this part. I really really encourage you to listen to DJ sets to get ideas. It’s given that there are many reasons why a listener might be engaged with your song – the quality of the mix, a

It’s given that there are many reasons why a listener might be engaged with your song – the quality of the mix, a Going back to the article

Going back to the article

Patience. this is perhaps the most prized trait a label will appreciate from you. In this fast paced world, patience is not only rare but it is also a quality that we all need to work on. It’s about having trust that things will work out in the end and that one’s results will be something that happens in some distant future. Parallel to patience, this goes hand in hand with trust. One goes with the other. It means to be able to have a bigger picture of things, that perhaps somewhere down the road, something great will be happening. Maybe not… but to not lose patience over delays is critical as these are common in the music industry.

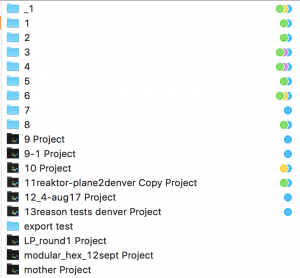

Patience. this is perhaps the most prized trait a label will appreciate from you. In this fast paced world, patience is not only rare but it is also a quality that we all need to work on. It’s about having trust that things will work out in the end and that one’s results will be something that happens in some distant future. Parallel to patience, this goes hand in hand with trust. One goes with the other. It means to be able to have a bigger picture of things, that perhaps somewhere down the road, something great will be happening. Maybe not… but to not lose patience over delays is critical as these are common in the music industry. Many DAWs can be setup to load a template as an initial starting point. Reason will propose a pre-made environment, and Studio One will propose if you’d like to setup a project for mixing to speed up your getting started time. Ableton Live doesn’t have that feature by default, but you can easily change that to open a custom startup project.

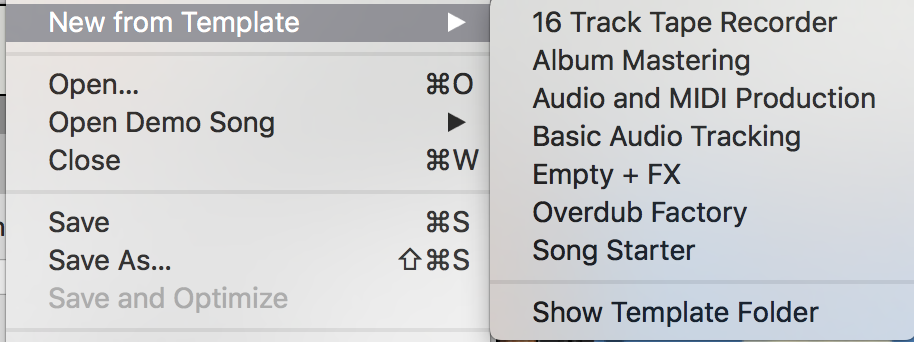

Many DAWs can be setup to load a template as an initial starting point. Reason will propose a pre-made environment, and Studio One will propose if you’d like to setup a project for mixing to speed up your getting started time. Ableton Live doesn’t have that feature by default, but you can easily change that to open a custom startup project.

That last point is crucial here. You can take the same compressor concept (ex. FET compression), but it will sound different from one company to another. There are no real universal standards on how to approach compression or EQing. An EQ can show you a curve but the filter in the back might slightly be different to give a color, for instance.

That last point is crucial here. You can take the same compressor concept (ex. FET compression), but it will sound different from one company to another. There are no real universal standards on how to approach compression or EQing. An EQ can show you a curve but the filter in the back might slightly be different to give a color, for instance.