Understanding Arrangements in Electronic Music Production

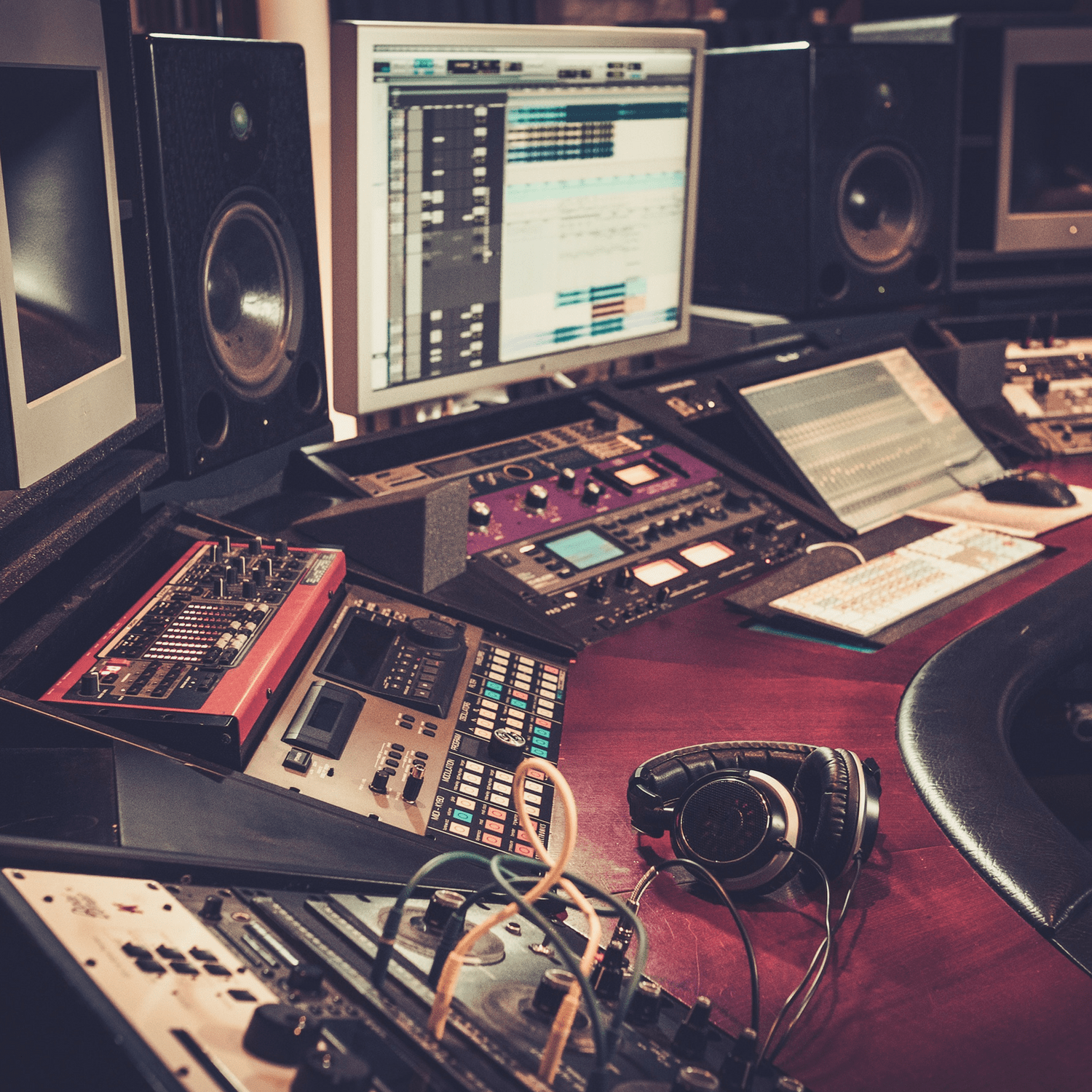

We can agree that a song is an idea, which is developed into a story. The word we use for that is arrangements. As I explained in a previous post, the arrangement phase follows creating a mockup and involves creating a timeline in which sounds come in and out. At least, this is how I approach it. As I work with clients on their production or mixing, I’ve been exposed to a variety of arrangements. What I see is that some genres often recur, and some are also overused. This post will cover multiple questions I get with arrangements, as well as how I teach various techniques.

Common Arrangement Types in Electronic Music

Depending of the genre, arrangements are meant to be adapted to fit the other songs of the same direction. But there is also a factor to take in account regarding the intention, or purpose, of the given song. When I do listening events or provide feedback for clients, I always ask them to answer a few questions:

- Who is this song for?

- Where and when should it be played?

- What is the context behind this project?

- What is the intention or purpose?

It’s always surprising to me to see so many artists making music without giving any thought to these points. One can make music freely, without considering the listener, which is a bold move, but this can raise some problematic points when it comes to feedback. But most of the time, people will have at least one idea of where their song is going. These questions, if answered early in the creative process, will help focus the approach to the music, and this will significantly impact the arrangements. There’s a category of clients who have lovely and catchy ideas, but they struggle to bring them to life. This is a common thread amongst newcomers to electronic music.

Good ideas without execution become tiring and unengaging. This is the stuck-in-a-loop syndrome, where people struggle to get out of an idea and turn it into a song.

Poor ideas with strong execution can still be exciting to listen to. Some of my favourite techno tracks feature a handful of sounds and melodies that are only 2-3 notes long.

Who is it for?

This is simply understanding that your music is not for everyone. If you try to please everyone, you’ll end up pleasing no one. Music that works focuses on a single audience and accepts that compromises must be made. Some music manages to reach broader audiences, but this is not an easy task. There is a consensus on what irritates in music that can create aversion. One way to see this is to remove as many divisive ideas as possible, while keeping the concept easy to understand. Divisive ideas are often what gives personality to a song, but they can make people feel uneasy at first. There is a thin line between what pleases and what does not. An example that comes to my mind is Gypsy Women by Crystal Waters. When it came out, 50% of people liked it, and the other 50% hated it. But it was being played over and over on the radio, growing on people’s mind and eventually got the recognition it deserved because it was pretty original at the time.

When it comes to electronic music, being intentional on the direction of the song can help make decisions easier on your arrangements. I like binary questions like these to help find the intention:

- Is it for DJS to play in sets?

- Is it danceable and meant to be mixed beat to beat?

- Is the song for early sets, peak or closing time?

- Is it meant to create a peak experience?

- Is it a tool?

I could go on about the various angles one can approach a song. But these main questions will directly influence how the song is built. There’s also the genre, which is not a binary question; even within a genre, there can be various levels of intensity. Some house songs can be mellow while others are bangers. Peak experience songs are meant to leave a profound emotional impact on the listener: they can be peak-time music, but they can also be beautifully written melodies for the closing track of the night.

Where and when should it be played?

As previously described, the moment and context will influence how the song is built. Early on, music usually has arrangements that are less inclined to have punch. Mellow arrangements involve executing the sound progression with more fade-ins and fade-outs, while maintaining a relaxed tone and avoiding tension-building. When it comes to music that is club-oriented, you’ll have some options on hand to make your song exciting, but this is genre-dependent, once again. There is also another point to consider, which is the context of where the music will be played:

- Home listening?

- Small club?

- Big club?

- Commercial Club?

- Festival?

While many people listen to festival music at home, there is some home listening music that won’t fit clubs because the context is just not appropriate. Home listening to music is intimate and leaves a lot of flexibility to explore subtle or audacious ideas. The difference between small and big clubs is often related to the intensity of the music. Some underground clubs are more open-minded when it comes to originality, while bigger, commercial clubs require music that appeals to a broader audience, as well as higher-energy, upbeat tracks.

What is the context behind this project?

Is this song an exploration of a genre or trying to emulate a label’s sound direction? Those simple questions relate to the context. We’re referring to the craftsmanship behind the work put into the song. Being aware of the context is sort of the original, or root, of the spirit of the creation of the music. If the context implies that you got signed and want to emulate the label’s direction, you’ll have a completely different context than someone making a song for their next DJ set. Being aware of your context is the first step in executing your idea.

What is the intention or purpose?

This is the fundamental question that will change everything, and it sums up all the previous questions. If you answered all the others easily, then this one will become obvious. Sometimes, the intention is clear and straightforward, but if it’s not, you might encounter challenges in building your song.

Arrangements 101

While I feel I could write an entire book on the topic, I’ll try to remain straight to the point about the essentials one should know right from the start.

The Essentials

Is there a minimum number of elements one needs to start making their arrangements? The simple answer would be no, but…

Once again, be aware that this will be a recurring point: your genre and intention will define what you need to start with. When I teach music production to newcomers, I feel there is an undefined’ level 1′ where one needs to learn how to create arrangements by copying those of references that one finds inspiring. Quite often, people give a lot of importance to the gear they need to make music, but one blind spot people frequently have is the quality of their influences and references. If you train your ears on questionable references, you’ll be building your inner vocabulary of arrangements on material that will lead to lower-quality results.

Studying your references will help you understand various points. It becomes the equivalent of learning how to write a book. There are a few points of interest to note, so let’s go through them here.

Song Form

This is how the song is built, with the number of sections. Also, there’s a concept I call Storytelling Perspectives, which involves dividing a song equally. Depending on your perspective, how you distribute it can yield balanced or unbalanced results. When I import a reference song into the arrangement side of my DAW, I put perspective points first, then check the song’s content to understand its sections. I love to see the correlation between the perspective and the sections. Sometimes it’s unrelated (e.g., unsimilar in the division points), while at other times, it’s almost the same, but with a few adjustments.

Arrangements organized with readability, colour coding and perspectives. Song by Barac analyzed for/with a client.

This example is how I read a song, and then, using ghost MIDI clips, I analyze how the arrangement is made. I place clips when I see a channel starting and draw them until the very end of the song. Sometimes I punch in the MIDI note of the given sound. This exercise provides a lot of information on how to build a song similar to one that I know works. One thing I also notice in songs that work well is a cohesive balance between the first third and the last one. Each has a part that the other doesn’t have, keeping the listener anticipating something to come. When perspectives are equal, the listener will intuitively know that something will happen at a given time, which rewards them for staying tuned. Also from this analysis, we see that this song starts strong with six elements right from the start, no break, and builds up. This type of arrangement is typical of techno, house, and minimal, where you want to provide a bed of intensity for the DJ to blend into their mix.

The main reasons I use MIDI clips are:

- You can quickly import the reference template within any project you’re working on. It will adapt to the bpm.

- You can import some of the channels and then test different sounds or instruments while keeping the pattern.

Tip: Define a colour coding that you’ll stick with through all your songs. This will allow you to open any old project and quickly get back up to speed.

Going deeper into the hook, we can now also analyze how things we built. This is what we refer to as “form” or, more specifically, “musical form”. Understanding the form will mean that you know the sections, such as these:

-

Intro / Build / Drop / Break / Drop / Outro (Organized, conventional, predictable)

-

Interpretation: Focused on energy cycles—build tension, release, rest, repeat. Great for dance floors, but often overused.

-

Tip: Try muting the first drop entirely and bringing it later than expected for a tension surprise.

-

-

Linear Progression / Techno Style (Simple, unconventional, hypnotic)

-

Interpretation: Evolution through subtle modulation. Encourages hypnotic, immersive listening.

-

Tip: Try working with 3-4 motifs only, but automate movement through FX, EQ sweeps, panning, or layering.

-

-

Loop-based Collage

-

-

Interpretation: Stream-of-consciousness or playful. Can feel chaotic or spontaneous.

-

Tip: Rein in the chaos by picking a key motif and returning to it as a “chorus” or anchor.

-

-

Hook Form

A hook in music is a short, memorable musical idea—often a melodic phrase, rhythmic pattern, vocal line, or sound—that grabs the listener’s attention and sticks in their mind. It’s usually the most recognizable part of a song and is designed to be repeated, often in the chorus or intro.

How you understand the hook of a song will give you insights into how to evolve your simple hook into something more. You’ve probably come across specific terms, so let’s go over a few basics.

-

A/B Structures (Verse/Chorus or Theme/Counter-theme)

-

Interpretation: Contrasts emotional states—such as question and answer, night and day, etc.

-

Tip: Instead of jumping A → B, try ABA, or ABAB’, where the last B is a variation to close a story arc.

-

- Development

- Is the hook remaining the same or developing through the song?

- If it’s the same, what about the effects and sound modifiers?

Hook expressivity

This is about understanding the DNA of the hook to help analyze it. This can be covered with a few simple questions.

- Is the hook a melody or a specific sound?

- If it’s harmonic, what are the primary key and scale?

- If it’s a melody, how many notes make the hook?

- Are the notes short or long?

- Is the hook over 1 bar? How long is it?

- Which Octave is the hook occupying? Is it expanding over multiple octaves?

- What is the rhythm composition? Fast? Slow?

- Is the hook involving neighbour notes, or is there a jump?

Hook’s family

A hook is rarely alone in a song to carry it through the entire arrangement. If that’s the case, it often evolves or morphs, while still having some modifiers that alter its character. But in other cases, the main idea will have a supportive companion. In Jazz, the main melody might be played by the entire band, but sometimes it is one specific instrument that leads the song, while others complement, support, and interact with it. I like to use family terms to describe the supporting roles, but I also encourage anyone to come up with their terms.

- Brothers/Sisters: These are usually closely involved in the composition of the hook with similar notes either in the negative parts of the hook or perhaps at the same time. These will often be the call and answer for the main idea.

- Cousins: They are similar to the hook but diverge from the original idea. This is often a decorative or accent piece.

- Father: I see the father as the root of the idea. A good example is a supporting pad that creates a tone, providing a grounding space for the family to evolve.

- Mother: This element is a source of nurturing. It’s a bit difficult to explain because we’re in the world of metaphors here, but I imagine it as a sound that seals the emotion of the song.

Not all songs are suitable for the whole family. Many songs have perhaps only a few elements. One element is the antagonist, which creates tension and generates potential conflict as the music evolves. If the song has tension and builds up, it will need a resolution at some point (often described as the drop), which the mother might provide.

Sound Order

Learning arrangements involve understanding how sounds come in, including their order. The best technique for understanding this is to note down in your arrangements where sounds appear and where they end. This technique is the best teacher for creating effective sound interactions to achieve a desired effect. Starting a song with all the percussion won’t have the same impact as if you slowly began with a pad.

Building templates and Readability

The first thing I do is to organize the channels for easy reading. Arrangements can become a mess as people work on it, and not having organization means missing the opportunity to understand what is happening. I want to be able to read and understand a song even before I press play. To do this, I need to organize the channels from top to bottom, in the order they appear. This means that the first channels that play should be at the top, followed by the others as they appear below. When working this way, arrangements take shape into a structure. You’ll see below a few arrangement examples, along with their names and some notes on the kind of effect they create.

A Classic Stairs Progression example.

This arrangement type is classic with a stair progression. One thing to keep in mind about stair progression is to be conscious of the buildup it creates, and that you’re engaging in what I call climbing to the top. You then need to think about climbing down. Stair progression is easy to understand, evokes a sense of assertiveness, and can build excitement. There’s an importance to keeping a relevant distance between each step. They all should keep the same timing to create a sense of predictability. If you bring a few sounds at once (in this case, Hook and Perc3), one can come with a fade in, but if you want to keep it punchy, that’s your decision. In this example, there is a sense of balance and a moment of tension half way with a rebuilt.

Climbing with the Valley example.

This arrangement is a different take, where the arrival at the top leads to what I call a valley (the open area after the peak). This creates a dramatic effect on the listener, but it also has the drawback of disrupting the energy. This might be appropriate for EDM, where breakdowns are essential, but they could create a moment of stillness on the dance floor. That might be what the artist wants, which depends of the intention.

Donato Dozzy analysis of an ambient techno track of his.

Simplicity always works. If the hook is complex, arrangements can be simple, and if the hook is simple, you could make things a bit more complicated with the narrativity. But in both cases, simple arrangements make it easier for the listener to engage with the song. I wouldn’t be surprised if Dozzy record most of his arrangements from a jam or playing live, and in many cases, he keeps things simple, but it always works. After analyzing his song, I was impressed by the straightforwardness of the arrangements.

DJ Sneak is always effective in every single of his house tracks.

I wanted to know how Sneak always pulls his arrangements because his music is so practical and fun to play. His formula is basically about having a core and then having various elements alternating on top. This approach is helpful for repetitive songs where the listener can focus their attention on a pattern, but then it shifts to the different upper elements that come in and out. That gives the listener an experience of being hypnotized and explains why house music has never gotten out of style since its invention. It’s simple, uses a limited amount of elements but is all about how they gel together. Simpler arrangements invite to analyze the patterns. They’re often over 2 bars long and alternating with variations every 4.

Melchior keeps it linear but introduces long valleys.

Melchior is one of those artists that, just like Sneak, creates an experience when you listen to his music. There is a lot of space in the repeating patterns, and he is not shy about letting sounds play on their own for a while. And it works. I wanted to analyze that song of his because it was so catchy that I wondered how he kept me hooked. The analysis revealed a very unconventional approach to his music, which pleases my brain.

Two techniques: Macro pattern repeat and channel substitution.

This snapshot covers the last two points I will share. The first is macro pattern repetition, which involves taking a pattern and creating a pause of equal duration (see the yellow line). One mistake people often make with music they find linear is not considering adding rests. Having a pause keeps the listener on the edge and gives a sense of slow, evolving progression. While many people feel that their music stagnates and will add more layers, the best solution is usually to subtract parts instead. A negative space creates room for wanting the sound to return. The other technique is channel substitution, which is simple and effective: if you want to remove a sound, add another one to compensate. In this case, the blue line gets a rest but is compensated with the light blue one. This is an excellent way to make swift changes, preventing the energy loss as the listener’s point of view shifts from one element to the new one. They might not even notice the change at first. This can be done with any sounds (ex., percussion for bass, vocals to kick, etc).

Duos, Trios, conversations.

The conversations between the parties are essential. See it like in jazz, where one instrument has a solo and then a duo with another. It’s the same for your elements. I find the perfect balance for a song is to have 3 interacting elements, as this gives you many options, as seen above. The 3 blue lines represent melodies:

- Dark Blue starts solo

- Dark Blue is in the duo with second blue.

- Dark blue goes quiet, and the three secondary blues then have a moment together.

- Dark blue comes back, forms a trio with two others, while one goes quiet.

This alternating energy creates many different sections you can play with throughout the song.

I hope this was helpful!

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!