How to balance a mix

In general, I find that there are certain common elements found in mixes I’m sent, and I’d like to share my thoughts on how to balance a mix. If you google “mixdown tips”, you’ll see that mixdowns have been covered in a lot of detail online, but most articles on the topic are geared towards rock music. Since I am dealing with electronic music and DAWs like Ableton, I thought adding my own perspective to help correct and polish different types of mixdowns might be beneficial.

Let’s run through a basic mixing exercise together. To do this, you’ll need an FFT—like SPAN by Voxengo—to analyze the overall frequencies in your mix. The more time you spend checking a frequency analyzer as you work on your mix, the more likely your mix will come out balanced and have fewer mistakes.

Why does a balanced mix matter?

Balanced mixes are important because you don’t really know how clubs’ PAs are EQed until you play on them. If a club has too much low end in its system, then a bass-heavy mix will sound incredibly messy. Yes, a DJ can tweak the mix , but it will never sound the same as if he/she started with a track with a nicely balanced mix.

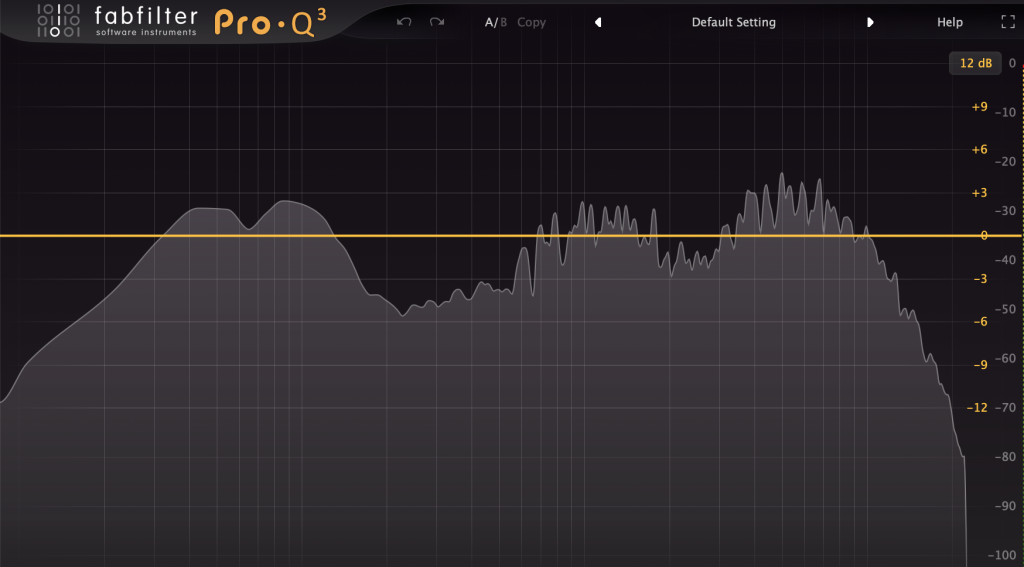

When people send me music to be mastered, they often forget to double check the frequency analysis of their mix, and sometimes it’s just not balanced.

A balanced mix (or flat, if you prefer) usually has a full range of frequencies more or less hitting 0dB on an FFT reader. You can go -/+3dB around it, but keeping it around 0 is the best. For electronic music, it’s pretty normal to have the low end sticking out by about +3dB though.

Now, the classic mixdown curves I see most are fairly common—they have something appealing about them, but also create downsides with risks.

“But I check masters, and they’re often not flat,” you say.

Well yes, that can happen, but the mastering engineer’s job is also to remove unwanted resonances before boosting. It’s always better to have something balanced that won’t need a lot of cutting before the engineer can make the critical decision(s) of boosting a range of frequencies.

That said, let’s examine some common mixdown curves I see that aren’t really balanced, according to how they look in a frequency analyzer.

How to balance a mix according to different types of mix curves

The Smiley Curve

This shape is well-known, and sometimes you’ll see EQ presets with this name—it means the lows and highs are boosted, hence the curve looking a bit like a smile.

The good: First impressions with this curve is that it’s instantly gratifying. Exciting feel, bright and shiny highs, and low end power—pretty much what humans love in music; foundation and excitement.

The bad: A lack of mid-range frequencies can mean that on a large system it feels hollow, confusing, lacks body, presence, and emphasizes hi hats and kicks over everything else, making the main theme of the song hard to discern. Harsh, boosted highs are also quite tiring on the ear and produce listening fatigue.

The fix: If you look at the FFT and your mix is smiley, there are a few ways to fix it. The first, is to manually readjust the elements who have the hot frequencies and turn them down. Highs are mostly likely high-frequency percussion, such as hats, but could be transients or the very upper part of synths and atmospheric elements. If you can spot which sound(s) have that range exaggerated, filter it with a low pass curve of 6dB/octave. Another way to fix this curve is to put a 3 band EQ on the master and lower the lows and highs, then boost the master for the loudness lost. The mids will magically appear and might feel overwhelming at first, but that’s simply because the human ear is sensitive to mids—more mids mean more presence and power, plus clarity on most systems.

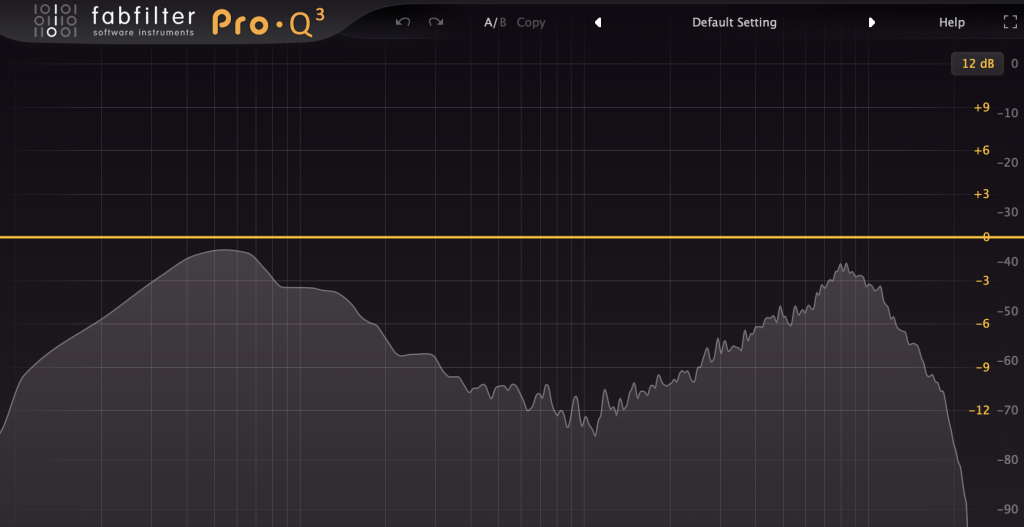

The bright mix

Bright mixes destroy my ears

A bright mix is dominated by an accentuation of the highs. Many of my clients frequently mix this way because it’s exciting and electric, but bright mixes also very harsh on certain systems and as previously mentioned, they’re very tiring on the ears.

The good: Excitement, air and powerful transients.

The bad: Bright mixes will sound rough at high volume level and I swear that in 50% of the time it will be played in a club, the DJ will have to turn down the high-EQ. If the system isn’t great quality, bright mixes can also create distortion.

The fix: Use a shelving EQ and turn down those highs. Look at your curve and see where the steep part starts (sometimes at 5khz, sometimes at 8khz), then just lower it down by 3-5dB until the FFT becomes a bit more flat.

Note: If you feel like you really need it bright, try to keep it under +3dB.

The bass-heavy mix

Bass-heavy mixes are very common in electronic music because of the lows needed to make people dance. It sometimes becomes a huge issue for me where clients really want their kicks to punch through, but a kick will sound powerful if it exists on a full-range frequency scale (also in the mids, and high mids).

The good: Bass-heavy mixes will be powerful and can blow away the crowd.

The bad: After a few minutes of pounding lows, if you can hear anything else, it feels very dull. Bassy mixes will sound muddy, messy, blurry, and insignificant. For instance, on a Sonos (like the one I own), all you’d hear would be a thump, thump, thump…annoying, not nice sounding.

The fix: Just like the bright mix, add a shelving EQ but work with the lows. I’d encourage you to revise your kick-design process if they sound too bass-heavy, and also get to familiarize yourself with how your favourite home sound system is calibrated.

The peaky mix

A “peaky” mix is my own term—it’s when I look at a mix and the curve has these big frequencies sticking out, while everything else is low (hence “peaks”).

The good: If done well, emphasizing certain peaks can be a good way to create dynamics in a song in terms of volume differences between your sounds. In some cases, it can create a sense of depth, but in doing so you demand a very active listening experience from the listener to be able to achieve this effect. This technique common in jazz, for instance.

The bad: Done wrong, a peaky mix just feels like there’s no power to it and the song will feel thin and some sounds will feel resonant.

The fix: Revise your mix entirely. Pull down the gain on the peaking sounds, then turn up the gain on the master to create something more even. Fixing peaks demands patience and practice.

The Gruyere mix

A Gruyere mix is one with hole(s)—on a big sound system, they can feel partly empty, or just wrong. Basically, the feeling of holes in a mix is a sign that it could tweaked to cover the missing areas.

The good: Truth be told, you can always live with a mix with holes. You won’t really face any serious issues, but your sound might feel flat.

The bad: Let’s say you could cover more mids with your percussion to cover a hole—then perhaps your percussion would feel more powerful. If your pads are lacking body at around 200hz, they will lack power. These holes are simply pointing out that some sounds could use a bit of tweaking.

The fix: Revise your mix. Try to see if you can boost weak parts of certain sounds. On the master, use a high quality EQ and gently boost the holes up, as that can make a difference.

The thin mix

A thin mix is one that, on the spectrum, looks good, but somehow doesn’t seem to drive at all.

The good: It’s gentle. Maybe you like it that way on purpose?

The bad: No power, no loudness, dull.

The fix: Add a compressor in parallel mode (50% wet) on the Master bus to give the mix a bit of thickness.

The punch-less mix

Punch-less means a mix just doesn’t punch, slap, or kick as it should.

The good: Non-punching mixes could be good if your music on the ambient side of things.

The bad: For dance music, you need at least some elements with punch, like the kick and/or clap.

The fix: Use transient shapers and/or compression with a slow attack and high ratio to turn your lifeless elements into something with attitude.

All these fixes need practice before you come out with a nicely balanced mix—I hope this has been useful advice on how to balance a mix!

SEE ALSO : The benefits and risks of using a reference track when mixing

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!